- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3890

Houthi Ship Attacks Pose a Longer-Term Challenge to Regional Security and Trade Plans

The immediate effects of the Houthi antishipping campaign are measurably serious, but the United States, Saudi Arabia, and other partners also need to prepare for the emboldened group to exert its newfound leverage in other ways beyond the Gaza war.

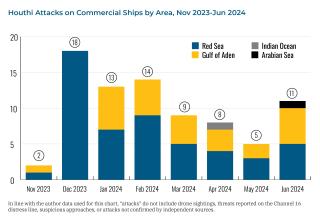

Throughout the Gaza war and the associated Operation Prosperity Guardian in the Red Sea region, The Washington Institute has been monitoring the Houthi threat to commercial shipping via its maritime incident tracker and, more recently, its Maritime Spotlight hub. Two things are clear from this data: the threat is still escalating considerably in quantity and quality, and neither the U.S.-led coalition nor the recently launched European Union Naval Force Aspides have been able to curtail Houthi attacks, which the group first launched in response to the fighting in Gaza.

In the five months since the United States and Britain began conducting military strikes in Yemen with non-operational support from various other countries, over 100 additional incidents have been recorded, including several naval interceptions of Houthi weapons. Some companies trading with Israel initially brushed off Houthi threats and kept operating in the region; eventually, the group began to attempt deadlier, more complex attacks. For instance, on June 12, the group attacked a bulk carrier using an uncrewed surface vessel (USV), which successfully inflicted serious damage on a commercial ship for the first time since November. The ship later sank, and one seafarer was reported dead. On June 13, the Houthis launched a double attack on a cargo ship using at least three missiles, leaving one seafarer severely injured and forcing the rest of the crew to abandon the vessel.

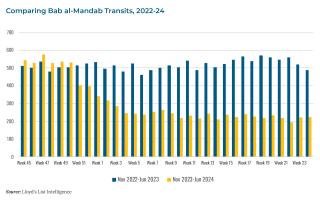

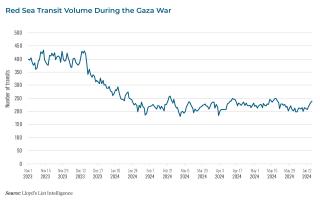

The growing risks have convinced multiple shipping companies to steer away from the region, causing a sharp drop in overall transits through the Bab al-Mandab Strait, one of the world’s most critical shipping lanes. Between June 10 and 16, traffic through the strait was down by more than 50 percent compared to week 24 of last year (see graph below). The attacks are expected to increase even further if the Gaza war continues or if Israel and Hezbollah escalate to a wider conflict in Lebanon.

Yet despite the understandable focus on the immediate maritime and trade effects of these attacks, more attention needs to be paid to how well-entrenched the Houthi threat has become, and how it might use its newfound leverage to serve different political agendas in the future. Although the maritime threat may gradually die down if a ceasefire is reached in Gaza, it will not disappear—rather, its effectiveness in disrupting global commerce will only embolden the Houthis.

How would a persistent maritime threat affect U.S. regional partners, some of whom had been planning to drive trade growth before the Gaza war by becoming global logistics hubs? Can they still leverage their strategic location between three continents if those continents remain partially disconnected by ongoing attacks?

A More Lethal “Fourth Stage”

On May 16, just days after Israel launched its offensive in Rafah, the leader of the Houthi movement warned, “We will seek to strengthen the fourth stage of escalation in terms of [number of attacks] and impact of strikes,” reiterating that the campaign’s purpose was to support Palestinians in Gaza. Since then, the group has expanded its target list—if a company has ships that call on Israeli ports, all of its vessels may now be targeted, even those that are not sailing to Israel. In the previous three “stages,” the Houthis focused mainly on ships that sailed to Israel or had known links to the United States, Britain, or Israel, though several of their attacks had unclear motives or were based on inaccurate information.

As promised, the current wave has also been more aggressive. Many attempted strikes have been intercepted by Western forces, but the overall quantity of attacks has been almost nonstop since May 23, when the Houthis launched a missile at the Malta-flagged bulk carrier Yannis (IMO 9401910). As in previous waves, the majority of these attacks have taken place in the southern Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea have each seen at least one confirmed attack during the Houthi campaign).

Several of the targets in the current wave were affiliated with Greek-based companies, including Eastern Mediterranean Maritime Limited (EASTMED), Evalend, and Grehel. Evalend owns the Tutor (IMO 9942627), the vessel that sank after being attacked multiple times by a USV and other weapons earlier this month. The Houthis have also made several questionable and unverified claims about attacks in the Indian Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Israel’s port of Haifa, in some cases involving alleged collaboration with Iran-backed Iraqi militias.

Earlier this month, the U.S. Defense Department stated that the Houthis have launched around 190 attacks since November 19, but “only a handful” have been successful due to the “effectiveness of coalition forces at stopping the attacks.” While assessments of the coalition’s operational impact may vary, the negative results of the Houthi escalation are undeniable—more ships are being targeted, several shipping companies continue to avoid the region’s waterways, and the Houthis appear to feel empowered rather than weakened. After enduring months of coalition strikes, they are still setting the goalposts for which companies can send vessels to and through the region, violating the most fundamental principles of freedom of navigation.

Meanwhile, commercial ships that do continue sailing through the Red Sea are taking unusual steps to lessen their risk of being attacked. Some have used their automatic identification system to signal that they have “no links to Israel,” while others broadcast messages such as “All Muslim crew,” “All Syrian crew,” or “China ship crew.” One vessel broadcasted “Russian crude oil” rather than indicating its next port of call. Even tankers laden with Russian oil have occasionally been targeted, however, typically due to inaccurate or outdated information about the ship’s ownership—for instance, the tanker Wind (IMO 9252967) was hit on May 18 while carrying Russian fuel oil bound for China, as detailed by the Institute’s attack tracker.

The Challenge to Regional Maritime Ambitions

By this point, the Houthis have proven they can substantially disrupt traffic between different trading regions, with giant firms such as the Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) and Maersk deciding to avoid the southern Red Sea. Consequently, the volume of container ships transiting the Bab al-Mandab has dropped by around 55 percent, according to the most recent data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence. Among other affected destinations, the number of such vessels visiting King Abdullah Port and Jeddah—Saudi Arabia’s largest transshipment hub and largest container port, respectively—decreased sharply earlier this year.

In May 2023, just a few months before the Houthis launched their attack campaign, Maersk announced a new ocean service connecting Middle Eastern markets to Europe and rotating between key ports such as Jeddah. By December, however, Houthi attacks had led Maersk to announce that it was suspending traffic in the Red Sea and rerouting vessels around the Cape of Good Hope “for the foreseeable future.” Last month, the company offered an even grimmer forecast: “The risk zone has expanded, and attacks are reaching further offshore. This has forced our vessels to lengthen their journey further, resulting in additional time and costs..., bottlenecks and vessel bunching, as well as delays and equipment and capacity shortages. We estimate an industry wide capacity loss of 15-20% on the Far East to North Europe and Mediterranean market during Q2.”

As for MSC, the Saudi Ports Authority announced in March 2023 that the company would be adding Jeddah to its Red Sea and East Africa-Red Sea shipping services. Since November, however, several of its ships have been directly targeted. The Houthis inaccurately regard the Switzerland-based firm as an “Israeli company,” most likely due to its trade cooperation with Israeli shipping companies.

Accordingly, Saudi Arabia and other affected regional states would be wise to prepare for a future in which their critical infrastructure remains under threat from the Houthis indefinitely. The group now has the capacity to launch more sophisticated attacks in different political contexts beyond the Gaza war, most likely with support from Iran. For instance, it could eventually decide to resume or escalate its maritime attacks if an Israel-Saudi normalization agreement seems imminent—especially if the Yemen conflict is not resolved. Thus far, Riyadh has preferred to remain on the sideline and avoid a confrontation with the Houthis, believing that this would only make the crisis worse and put Saudi vessels at risk of attack.

Red Sea stability is crucial to the kingdom’s ambitions for expanding its logistics sector—a key element in both its National Industrial Development and Logistics Program and its wider Vision 2030 strategy. Over the next few years, Riyadh plans to increase the competitiveness of its ports and enhance their international connectivity. Yet establishing a global maritime logistics center requires a stable environment—not just in the northern Red Sea, where the Saudis recently launched a new shipping service in partnership with the French giant CMA CGM, but also in the highly volatile southern Red Sea.

According to some projections, the current Houthi attack campaign will continue for at least the rest of this year, and many commercial vessels will keep avoiding the Gulf of Aden and southern Red Sea until 2025 or beyond. A Gaza ceasefire could ease the attacks somewhat, but even then the Houthis might not halt their campaign entirely. Although some ship owners have seen their profits increase due to higher freight rates, the overall impact on maritime traffic and global supply chains has been severe. Gulf states are hardly immune to these effects, so Washington should urge them to find a diplomatic means of halting the attacks, regardless of what happens on the separate U.S. diplomatic tracks in Gaza and Lebanon.

Finally, Washington and its partners should include the potential threat of long-term Houthi escalation in their military planning. Earlier this month, the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower carrier strike group left the Red Sea, where it had been deployed to counter Houthi threats since late last year. If the current campaign escalates further, or if the group dials up its attacks in the future, Western naval forces may need to deploy even more assets to protect commercial ships.

Noam Raydan is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute.