No sanctions relief should be granted without nuclear concessions, and a “less for less” deal may be the best way of reaching a viable compromise in the near term.

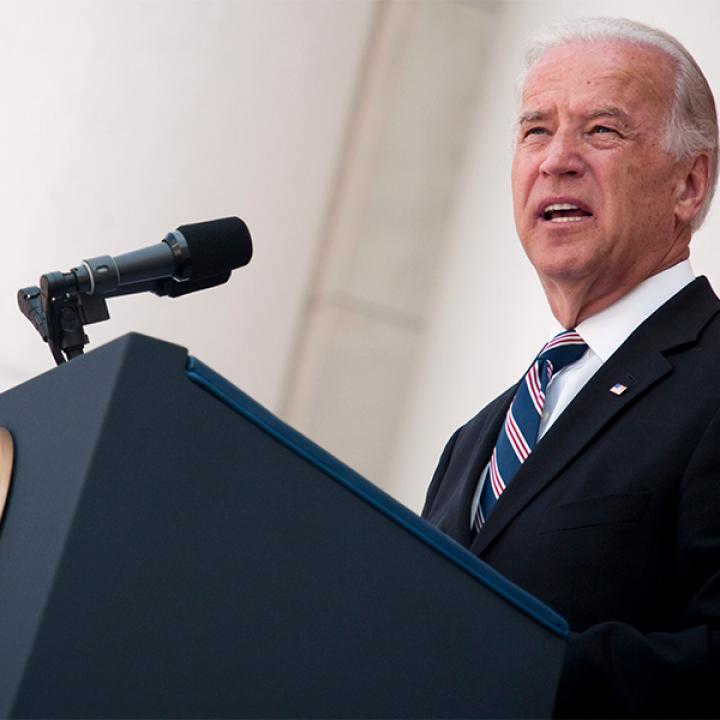

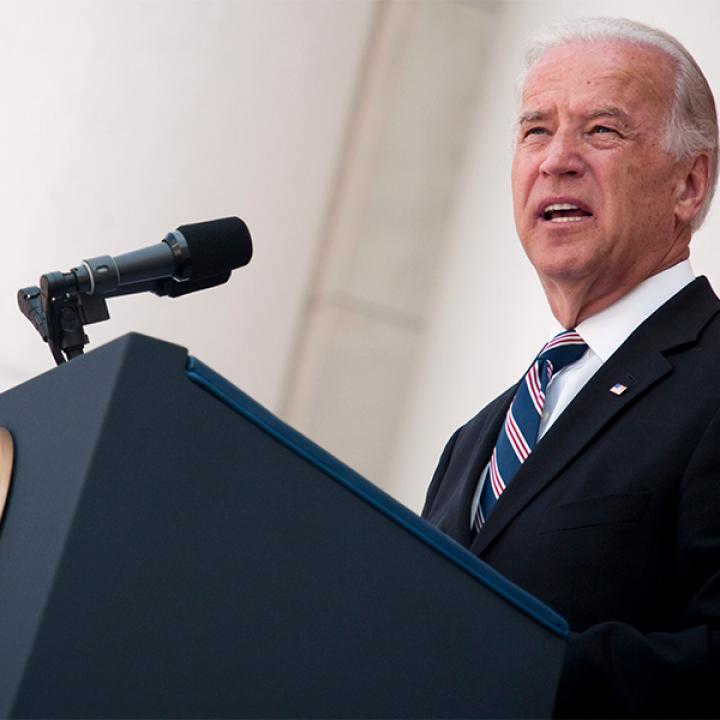

The U.S.’s relationship with Iran will never be easy. Not even President-elect Joe Biden’s readiness to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal, also known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, will be of much help. He has made it clear his goal is Iran’s compliance. But will anger over the killing of nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh and the small window of opportunity before June’s presidential election rule out diplomacy in the near term? Probably not, because Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei knows that Iran needs sanctions relief, but he will press for the U.S. to relax sanctions before Iran does anything.

The Iranians can get back into compliance with the 2015 deal by respecting the limits imposed on the number of their centrifuges, the level to which they can enrich, the amount of low-enriched uranium they can accumulate, dismantling two cascades of installed advanced centrifuges, and so on. For the U.S.’s part, it can again suspend sanctions, providing desperately needed economic relief for Iranians. But it would still take four to six months for Iran to get back into compliance with the nuclear deal. Will the new administration provide sanctions relief even as Iran continues to violate the JCPOA’s limits? The Iranians are not only insisting on continuing to do so, but they are also demanding compensation for the cost of the sanctions that the Donald Trump administration imposed on them, claiming with some justification that they continued to respect their obligations under the terms of the JCPOA for a full year after Trump stopped respecting the U.S.’s.

Even if the new administration refuses to provide compensation but offers immediate sanctions relief, with Iran only beginning to take steps to comply again, Congress’s Republican critics of the JCPOA are likely to cry foul. They will interpret as fundamentally mistaken any moves that reduce the U.S.’s leverage while Iran is neither in compliance nor changing any of its destabilizing behaviors in the Middle East. Ironically, that is likely to create a problem for both the president-elect, who wants to restore bipartisanship in foreign policy, and for Iran, whose leaders will want assurance that any agreement won’t simply be reversed in 2024 if American elections produce a different administration.

The Biden administration will have to reconcile a number of conflicts if its Iran policy is to have any chance of success. First, European nations want the U.S. to return to the JCPOA, while most congressional Republicans are likely to oppose any return to the nuclear deal that does not address its sunset provisions, ballistic missiles or Iran’s troublemaking in the Middle East.

Second, the new administration will feel the urgency of re-establishing limits on Iran’s nuclear program even as it addresses the other issues, but it doesn’t want to hold understandings on the nuclear program hostage to progress on the ballistic missile or regional challenges.

Third, the president-elect recognizes that Israel, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates want reassurance about the U.S.’s moves toward Iran, lest they act in ways that can complicate American strategy. But those countries are dubious about the JCPOA, fear the U.S. will surrender its leverage prematurely, and worry that the Biden administration’s stakes in the negotiating process will lead it to turn a blind eye to Iran’s threats to its neighbors.

Lastly, even as the Biden administration seeks to preserve its leverage on Iran and demonstrate the high costs of its bad behavior, it also wants to be able to offer incentives for better behavior toward its regional neighbors.

While difficult, it is possible to reconcile these conflicting aims. But it requires thinking in more limited terms. Precisely because it won’t be so simple to rejoin the JCPOA, the Biden administration should make a virtue of necessity: The U.S. should continue to declare its readiness to rejoin the JCPOA and negotiate a successor agreement—something that reassures the Europeans and sends the message that the Biden administration respects multilateral agreements—but also make clear that a more limited understanding that scales back Iran’s current nuclear posture need not wait, and that limited relief can be given for such moves. For example, the International Atomic Energy Agency has reported that Iran has 12 times the amount of low-enriched uranium on hand than permitted under the terms of the JCPOA; the administration could seek a cutback from the current 2,400 kilograms to 1,000 kilograms and the dismantling of the two cascades of advanced centrifuges that have been installed. In return, the U.S. could unfreeze the access to some of the accounts that hold Iranian foreign currency reserves while still keeping sanctions in place.

The virtue of this “less for less” deal is that it increases Iran’s breakout time to developing weapons-grade fissile material; preserves the U.S.’s leverage; doesn’t require both congressional Republicans and the U.S.’s Middle Eastern allies to embrace the JCPOA, a symbol they find problematic; and can buy time to do what Biden has made clear he wants to do—namely, negotiate a successor agreement to the JCPOA that extends its provisions while also addressing Iran’s aggressive posture in the region. Before adopting such a position, Biden should consult with Congress, European allies, and with the Israelis, Saudis and Emiratis. The Europeans, while favoring a return to the JCPOA, will support an American move that limits the Iranian nuclear threat through diplomacy even if it offers a more limited agreement initially. Congress and the U.S.’s friends in the Middle East will want to understand American aims and how it will seek to preserve its leverage.

Of course, the Iranians have a say in what is possible. Despite defiant talk, Khamenei knows the Iranians need relief and will look for a way to get it. They must not get it for free.

Dennis Ross is the counselor and William Davidson Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute. Originally published on the Bloomberg website, this article is drawn from the Institute’s forthcoming presidential transition memo on U.S. policy toward the Iran nuclear challenge.