- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

How to End Saudi Arabia's War of Paranoia

Repartitioning Yemen into separate northern and southern entities may be the only way to resolve its brutal war and beat back its al-Qaeda franchise.

Why should Americans care about Yemen? Average Americans probably couldn't find this remote southwestern corner of Arabia on a map. But it's time for them to learn. Yemen's civil war concerns Americans because their close but often awkward ally, Saudi Arabia, has persuaded them to take part in it -- and, alongside that brutal war, there's another that the United States initiated and has no intention of ending anytime soon.

How can the United States ensure the former, Saudi Arabia's war of choice, doesn't interfere with the latter? The answer could be to follow the 1953 deathbed advice of King Abdul Aziz, known as Ibn Saud, who supposedly said, "Never let Yemen be united." Yemen is a problem that probably won't be solved until it is dissolved.

Paranoia has long been the basis of Saudi policymaking on Yemen. It used to be paranoia about the Yemenis themselves; now it's about Iranians. Yemen's Houthi rebels are variously "Iranian-supported," "Iranian-backed," or "Iranian-influenced." The last is my preferred description since it clarifies that, while they model themselves after Lebanon's Hezbollah and have adopted the slogan "God is great, death to America, death to Israel, damn the Jews, power to Islam," they ultimately want to be masters of their own fates more than Iranian surrogates. (And as members of the Zaidi sect they are only Shiite-like rather than actual Shiites.)

It's clear the Houthis are a direct threat to the internationally recognized (and Saudi-allied) Yemeni government of President Abdu Rabbo Mansour Hadi, whom they forced to flee the country after joining forces with former Yemeni President and longtime Saudi nemesis Ali Abdullah Saleh (who used to oppose the Houthis until he was forced from power in 2012). But there is good reason to doubt these rebels pose a direct threat to Riyadh, outside the confines of Saudi paranoia.

Nonetheless, as an apparent quid pro quo for tolerating Washington's nuclear rapprochement with Tehran, Riyadh has demanded U.S. support for the Saudi-led coalition fighting to re-establish in Sanaa the rule of Hadi. (Hadi, for the present moment, prefers the greater security of a Riyadh hotel suite.) There's an additional factor, which makes the favors run 2-to-1 in Riyadh's direction: Washington wants Saudi involvement and a stamp of approval for the U.S.-led coalition fighting the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq.

Fear, if not quite paranoia, could also describe official Washington's attitude toward Yemen. Its rocky hillsides have been the training areas for Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which helped prepare the 2009 Northwest Airlines "underwear" bomber and the 2015 Charlie Hebdo killings in Paris. A terrorist incident in the United States with a Yemeni address on it is a realistic possibility, and the American officials who know it are prepared to go very far to prevent it from being realized. A successful attack on a U.S. Navy ship similar to the suicide speedboat that crippled the USS Cole in Aden harbor in 2000, they feel, would be almost as bad.

Until war broke out with the Houthis last year, U.S. Special Forces operated out of the Anad Air Base just north of Aden, playing whack-a-mole against jihadis, with occasionally more significant successes, such as the killing of Anwar al-Awlaki, the fiery preacher (and U.S. citizen), by a Hellfire missile in 2011. Now U.S. operations are conducted from Djibouti, on the other side of the Red Sea, in Africa. As before, drones are a major part of the effort. There are also, semi-clandestinely, several dozen U.S. special operations forces on the ground.

There's a crucial difference in Saudi and U.S. interests that quickly becomes apparent. Whereas Riyadh's thinking is dominated by Iran's support for the Houthi rebels who control the capital and much of what was once North Yemen (or, more formally, the Yemen Arab Republic), Washington's anxieties focus on the south, the territory once known as the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen. (The modern state we call Yemen was only formed when those two countries unified in 1992.)

The southern expanse of Yemen from the Bab el-Mandeb strait to the border with Oman has technically been liberated by the Saudi-led Arab coalition. In reality, forces of the United Arab Emirates did most of the heavy lifting and now, with residual government forces, have control over the port city (and old capital) of Aden as well as Mukalla farther east. But AQAP continues to find sanctuary in the large stretches of the south where the Yemeni government, and its Arab allies, struggle to maintain control. Fighters claiming allegiance to the Islamic State are also active there.

Washington's and Riyadh's separate wars are bound together in a manner not necessarily obvious to outsiders. The Royal Saudi Air Force and the U.S. Air Force are sharing Yemen's airspace and adjoining, even overlapping, battle space. The two countries have to cooperate and therefore largely tolerate the behavior of the other party.

But that tolerance is under strain. Even before the horrendous Oct. 8 bombing of a funeral gathering in Sanaa in which more than 140 were killed and several hundred injured, U.S. concern for Saudi tactics had meant reduced levels of cooperation. Inflight refueling was curtailed, meaning that Saudi F-15s could not loiter in Yemeni airspace, waiting for targets to present themselves. And cooperation was reduced on "targeting" -- the curious technical word meaning what size of bomb to drop, from what height, from what direction, and even at what time of day, the latter so as to reduce "collateral damage" or, more accurately, civilian casualties. The Saudis had already been targeting clinics and schools, and the justification -- that the Houthis were placing military stores and headquarters in or close to them -- was wearing thin.

The bombing of a funeral two weeks ago was both a humanitarian catastrophe and a major tactical disaster for the overall strategy of the anti-Houthi war. Even though the target was a Yemeni politician allied to the Houthis, bombing such a gathering was contrary to the ethics of the U.S. military. The Saudis only admitted to "coalition aircraft" being involved, a phrasing that suggests the unfortunate reality that they were American-supplied F-15s, carrying American-made munitions. Washington's power centers -- the White House, Congress, and the media -- screamed in horror. The blame was spun onto overexcited anti-Houthi agents in Sanaa and the fact that the target was approved at only a low level in the military hierarchy.

The awfulness of the wake-cum-mass-explosive-cremation was overtaken in the news cycle only when the Houthis responded by launching two, perhaps three, unsuccessful missile attacks on the destroyer USS Mason in the Red Sea north of the Bab-el-Mandeb. The United States retaliated by launching Harpoon missile strikes, which pulverized Houthi coastal radar facilities but caused zero collateral damage.

A three-day cease-fire is supposed to come into effect to give a chance for diplomacy by United Nations envoy Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed of Mauritania. Largely dependent on food imports, Yemen is on the cusp of a humanitarian crisis. It is probably too much to expect the Houthis and their supporters to lay down their arms. Previous cease-fires have collapsed after Saudi Arabia detected alleged infringements and re-launched airstrikes. This cease-fire can theoretically be renewed; it is an open question whether it will be.

The U.S. strategy should be to maintain a cease-fire that could be brokered into a power-sharing arrangement in the north. Hadi, Washington's and Saudi Arabia's man, technically controls from his Riyadh hotel suite the majority of Yemen territory. Unfortunately that land is the empty part of Yemen, with perhaps a population of only 3 million. The Houthi-Saleh alliance controls much less of the ground, but the mountainous part is militarily defensible. Additionally, this territory is home to more than 20 million people, the bulk of the country's population.

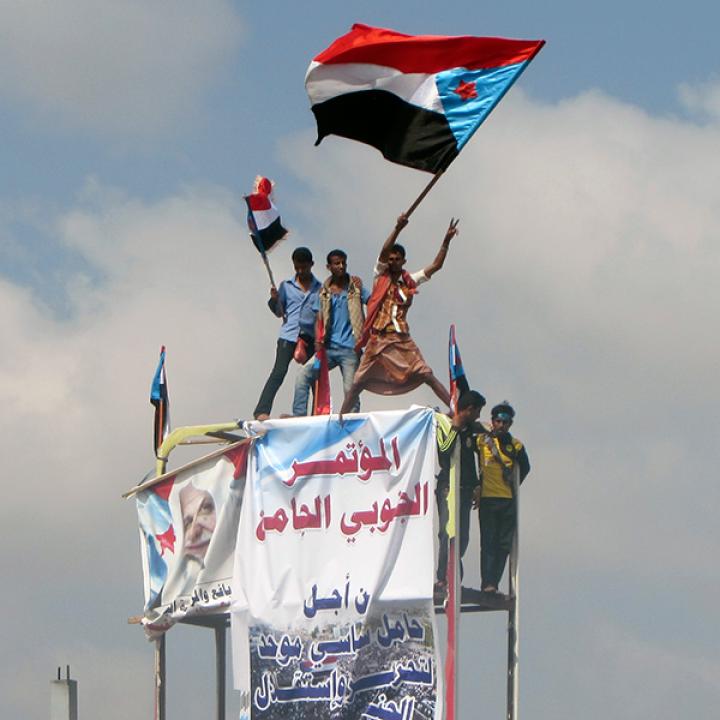

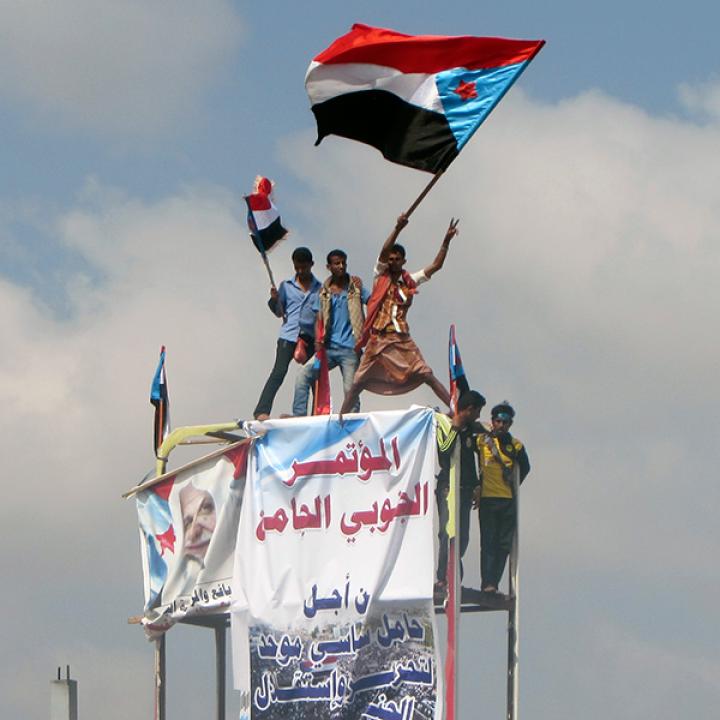

The partition of Yemen, a return to Ibn Saud's deathbed wish, should have a clear logic for all sides. The south wants it. Hadi himself may prefer it. The crucial local foreign power in the south, the UAE, is also said to think it is the best option. Distracted by its involvements elsewhere, Iran may not oppose it. It may depend on whether Saudi Arabia and, more particularly, its defense minister and deputy crown prince, Muhammad bin Salman, can be convinced of the wisdom of his grandfather's deathbed words.

Barring another outrage in Yemen with civilian casualties or a terrorist attack in the United States, Washington's efforts over the next few months of political transition at home are likely to be limited. But the problem of Yemen, or of the two Yemens, will be waiting for the next U.S. president.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Gulf and Energy Policy Program at The Washington Institute.

Foreign Policy