- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

How to Make Russia Pay in Ukraine: Study Syria

Also published in 19FortyFive

Washington needs to show Putin that this will not be the limited intervention he was able to get away with in Syria, but rather a catalyst for dramatic NATO entrenchment and strategic setbacks.

Russia is poised to invade Ukraine in the coming days. This Moscow-engineered crisis presents the most defining challenge to European security since the end of the Cold War, and its seismic waves are rippling worldwide. While all nations have enduring security concerns vis-a-vis their neighbors, Russian President Putin’s concocted crisis provides zero justification for further aggression. One way or another, this problem is here to stay for the foreseeable future. The West must make Putin lose—and lose big. Here, Moscow’s Syria intervention provides useful lessons.

Lessons from Russia’s Strategy

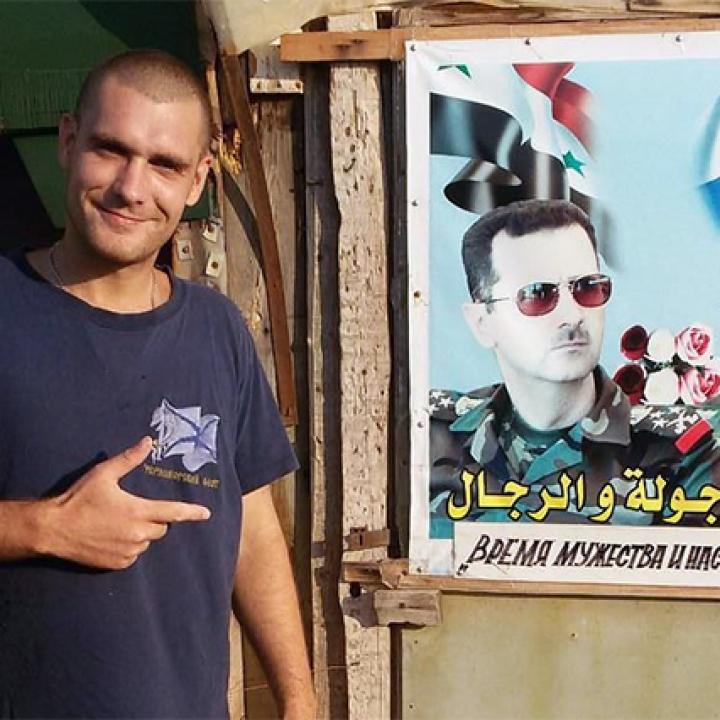

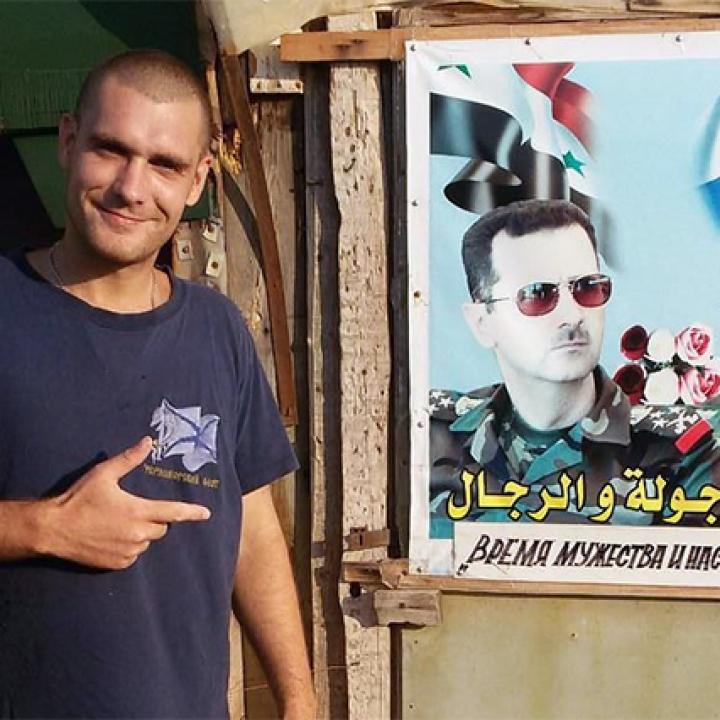

Moscow pursues a strategy of “limited actions abroad.” Syria is the prime example of this approach. When Putin intervened in the country in September 2015 to save dictator Bashar al-Assad, Moscow emphasized the use of aerospace forces over ground troops and set up an anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) bubble to deter the West. Indeed, Russia’s Syria campaign presented elements of aerospace warfare that, it would be fair to say, have come to define Russia’s evolving way of war. This approach involves the employment of multi-domain high-tech long-range precision weapons to include those in cyberspace against civilian and military targets, in addition to large-scale bombing campaigns and airstrikes.

The Syria experience suggests that if Moscow proceeds with open conflict in Ukraine, it will likely set up a more powerful A2/AD bubble than it did in Syria, through the use of its air force and army’s long-range precision fires. Moscow’s current military posture also clearly signals this scenario, for example, recent satellite imagery revealed the arrival of Iskandar-M cruise missiles, Su-34s, along with S-400 air-defense systems and other weaponry. Moscow is setting up the capability to employ long-range precision strikes within this protective A2/AD integrated air defense umbrella. Alone, the Ukrainian Air Force and Navy have no chance, let alone Ukrainian armor and mechanized maneuver forces.

In Syria, the West failed to raise the costs of Russia’s military engagement, which allowed Moscow to entrench its military presence on the strategically-vital Eastern Mediterranean. This position now bolsters Russia’s position in the Black Sea and adds to the pressure on Ukraine. The West can learn from the failure of inaction in Syria and put him in a military dilemma of getting engaged on a bigger scale than he wants to, and create exactly what Putin avoided in Syria—a quagmire.

Ukraine’s Encirclement and the Black Sea

First, the West should ensure proper support for the Ukrainian military; it must provide aid that changes Russia’s decision calculus. To give an example, providing the Ukrainian Navy with refurbished US Coast Guard Island Class patrol boats was an excellent idea. But providing them with no offensive missile capability makes them irrelevant not only in the Black Sea and in deterring Russia, but in modern military conflict as a whole. Defensive capabilities have yet to deter Russia.

At present, the Kremlin has taken a three-front approach to surround Ukraine: along the Belarus border, to the north all the way into Donbas in the east, and lastly, along Ukraine’s coast which includes the Sea of Azov and Crimea. In addition, the Russian navy amassed ships in both the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Regardless of what transpires in Ukraine, the Black Sea must remain a contested environment. This means providing the NATO Black Sea Navies with real capability to impose costs on the Russian Navy.

Russia’s modernization of the Black Sea Fleet, to include air and missile forces, created what analysts dubbed a “Russian lake.” Russia’s seizure of the Ukrainian coastal areas, let alone the entire eastern portion of Ukraine, will provide Russia with even greater leverage over the region and the ability to project influence into the Mediterranean. NATO must take action to undermine this by building forces that can deter Russian actions and challenge their maritime superiority.

This requires for once listening to the Ukrainians, as they often know the Russians better than the West does. Admiral Igor Voronchenko made repeated calls during his time at the helm of the Ukrainian Navy to help the country establish a “mosquito fleet” of small, fast, lethal attack craft. His calls went largely unheeded. The West must evaluate how it can best provide our Black Sea NATO allies with real capabilities that alter Russian thinking.

Reinforcements, Opposition in Exile, and Insurgency

Russia’s current envelopment of Ukraine eliminates freedom of maneuver for the Ukrainian ground forces. Russian forces will be able to systematically eliminate them using long-range fires and air superiority operating under an integrated air defense umbrella. Russian air supremacy will ensure Ukrainian forces will not be able to operationally reinforce at any point of attack because if they move they will get hit. Conversely, in the face of the likely ground assault that comes on the heels of a Desert Storm-like aerospace attack, the Ukrainian Army will get eliminated if they stand and fight, much like the preponderance of the Iraqi army. The US and NATO have to alleviate that pressure and ensure the Ukrainian army can get reinforcements.

Knowing Putin has explicitly asked for a return to NATO’s 1997 military locations, this crisis reveals what the West should do instead. The US Army should place long-range fires in sufficient numbers to put the Russian Army within range. This is not about targeting Moscow, but the Russian Army’s correlation of forces and means calculus along NATO’s periphery. These capabilities must be at a minimum deployed permanently and rotationally to Poland and Romania, and the Baltics respectively. The West should put Putin in a position where he has to consider permanently reallocating forces that he has transferred from the Eastern Military District to the West (Belarus). This not only would be unpopular with the Belarussian population but would increase Russian vulnerability vis-a-vis China and within its far east.

In the event of a full-scale invasion to effect Ukrainian regime change, another key element in raising the costs for Putin is ensuring protection and extractions of key individuals to establish a Ukrainian government in exile. If this results in a direct conflict with Russian special operations, U.S. and NATO forces have to stand their ground. A Russian invasion force will likely attempt to systematically eliminate key government figures from the national down through the local levels. Indeed, last month, the UK government had alleged an earlier Russian plot to overthrow the Ukrainian government. By sustaining a real Ukrainian government in exile we will ensure an insurgency has organization and initial direction. So, in the same vein, the West must ensure support for a valid insurgency, especially because Ukrainians will fight. They understand the stakes and know exactly what they are fighting for.

Lessons of Diplomacy

Syria, for its part, also offers a valuable lesson on how to conduct diplomacy, especially since wars are settled through diplomacy, not by military means alone. In Syria, Moscow deployed a whole of government approach, not simply brute force alone. The Kremlin convinced all sides that Russia could be part of a solution rather than part of the problem; something we go into more detail in a paper with my colleague Andrew J. Tabler. In Moscow’s view, military actions are subordinate to and in direct support of the political objectives of the Russian leadership. Since the end of the Cold War, this approach to conflict has been seemingly absent from U.S. and NATO military operations.

Russia’s chief of General Staff Valeriy Gerasimov emphasizes a four to one ratio of military to non-military means. This means that the entirety of diplomatic, informational, military, and economic activities are mutually supporting in the achievement of the Russian leadership’s political objectives. The Russian state is deploying the same strategy towards Ukraine, using all elements of coercion and compellence to shape NATO’s resolve to confront Russian aggression.

Russia has no disconnect between those who do diplomacy and those who go to war, unlike in the West. This is why the West often wins battles but loses wars. To increase pressure on Putin, the West must approach conflict using all the pillars of power to match Russia’s “decision-centric” warfare.

Gains from a Loss?

Putin went into Syria knowing it was a fight he could win. In Ukraine, he needs to see how much he will lose. Both Syria and Ukraine for Putin were about undermining US influence, credibility, NATO cohesion, and the European security architecture. Sanctions alone have not changed Putin’s behavior. NATO must go further this time and bring into question the very reasoning he pursued by delivering unrealistic demands to Western leadership. The West must view both conflicts through this lens, especially since the Mediterranean straddles both Europe and the Middle East. This requires increasing NATO forces and capabilities not only across Eastern Europe but also across the Mediterranean, to push Putin to reassess Russia’s force postures due to the developing disadvantageous correlations in forces and means.

Ukraine, for its part, as Professor Rory Finnin noted, is Russia’s competitor “in the realm of political values.” Indeed, historian Serhii Plokhy described in his book Lost Kingdom that the Russian state began its existence by crushing Novgorod, a key center of Kyivan Rus, and a democratic rival to authoritarian Muscovy. Over the coming centuries, the Russian state only changed the means by which it pursued its goals, but not the goals themselves.

Sometimes only a deep, shattering loss based upon a faulty calculus of one’s decision-makers can cause a fundamental reevaluation of core beliefs. To be sure, the West has already signaled that it is prepared to go farther than it ever had before. But it needs to follow through and show that Putin’s engineered crisis will now bring about the very things regarding NATO he has demanded to be righted.

But what is more, paradoxically, it could lead to a gain the world has never truly seen before—a fundamentally transformed Russia, one where the ruling siloviki who hijacked Russia’s post-Cold War democratic evolution are delegitimized, a Russia that is at lasting peace with itself and its neighbors.

Anna Borshchevskaya is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute and author of the book Putin’s War in Syria: Russian Foreign Policy and the Price of America’s Absence. This article was originally published on the 19FortyFive website.