- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3593

How to Preserve the Autonomy of Northeast Syria

To offset the destabilizing measures coming from Turkey and the Assad axis, Western governments need to offer more development assistance—but in a targeted way that reassures local authorities and minimizes mismanagement.

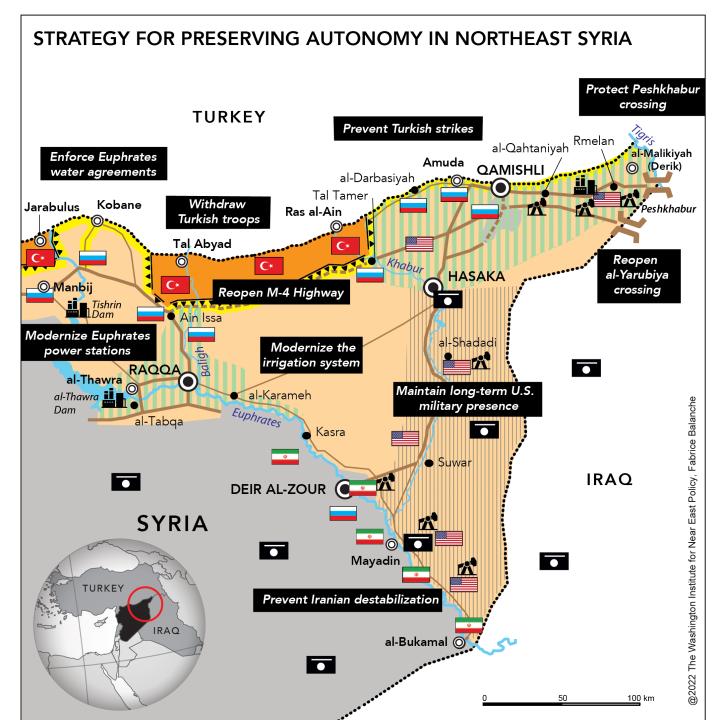

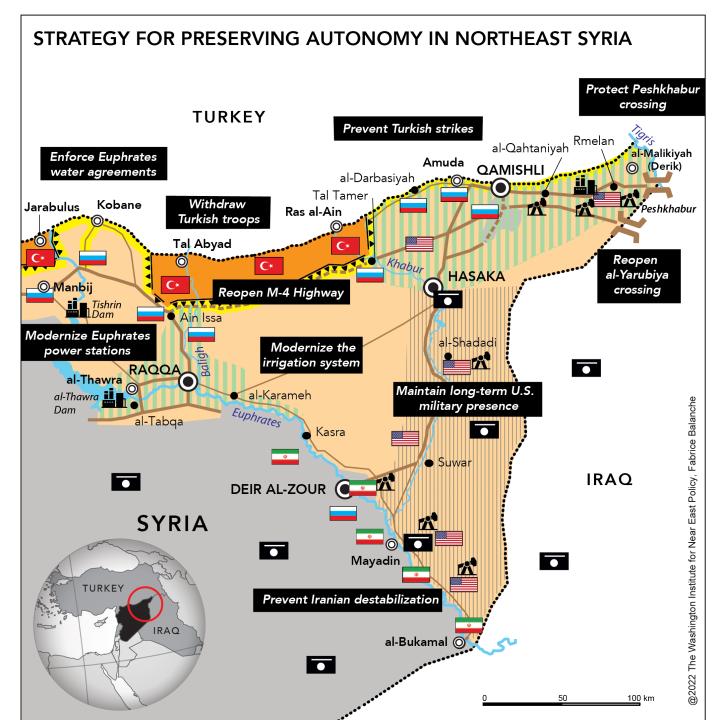

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) finds itself in an increasingly precarious political, economic, and security situation today. The threat of Turkish attack looms perpetually at the border, and although there are no widespread calls for the return of the Assad regime, some residents are losing confidence that the Kurdish-led AANES can provide safety and stability. The recent Islamic State attack on al-Sinaa Prison proved that jihadists are still active in the region, and the widespread frustration in poverty-stricken Arab areas may give the terrorist group fuel to recruit a new generation of fighters. If the United States and its Western allies hope to keep the AANES from collapsing, now is the time to redefine their strategy there.

Shortages in Energy, Food, and Water

This winter has been particularly cold in the AANES—the government has not provided residents with heating fuel since November, and purchasing it on the black market is prohibitive. Cities generally have just four to six hours of electricity per day, and villages one to two hours. Privately purchased generators can provide a few additional hours but never a full day’s worth, again due to prohibitive costs and lack of fuel.

The energy shortage can be partly explained by the low water levels in dam reservoirs along the Euphrates River—a result of local drought, Turkey’s water-retention policies further upriver, and massive pumping of groundwater. As a result, the old turbines in local hydroelectric facilities do not have enough flow to be properly powered. Fuel production is down as well, partly because the area’s oil extraction infrastructure needs to be modernized, but also because the AANES has been exporting more of its oil to the Assad regime and Iraq in order to obtain more revenue.

Regarding food supplies, subsidized bread is now rationed, and government facilities have been substituting some of the wheat in loaves with corn or soy flour. Similar to fuel, residents technically have the option of buying larger amounts of better-quality bread from private bakeries, but it is eight times more expensive—around 2,000 Syrian pounds ($0.50 USD) for a one-kilogram bag. Notably, local monthly salaries range from 150,000 pounds ($37.50) for manual workers to 300,000 pounds ($75) for secondary school teachers and soldiers. Indeed, constant devaluation of the pound has caused a massive decrease in purchasing power, since the AANES does not have sufficient revenue to revalue wages.

Aside from fuel, bread, and a few other food products, most goods consumed in the AANES are imported, since there is practically no local industry. The region’s economy is therefore heavily dependent on a few crossing points with regime-held territory (Manbij, al-Tabqa, Deir al-Zour), Turkish-controlled territory (north of Manbij), and Iraqi Kurdistan (Peshkhabur).

NGOs are attempting to help the AANES with many of these challenges, including structural water shortages linked to cyclical droughts and global warming. Renovating the irrigation and drinking-water systems is a top priority for development aid, and the rehabilitative efforts conducted so far have been successful. Yet simply restoring systems that were inadequate before the war will not be enough to address growing water challenges.

For example, the city of Hasaka has suffered a water shortage since its main source, the Alouk pumping station near Ras al-Ain, came under Turkish control during the major offensive of October 2019. The Suwar Canal was extended to draw water from the Euphrates, but that has not been enough to cover the needs of the area’s estimated one million inhabitants. The shortage is partly due to the fact that available electricity is insufficient to transport the necessary amounts of water over 250 kilometers. In addition, residents of the Khabur Valley along the canal’s route have increased their illegal pumping, such that Hasaka is down to around 50 percent of its normal supply. Again, NGOs are helping the city with this problem via temporary measures, but they are no substitute for a state with an integrated water policy—and the same goes for many of the other sectors required to resume normal life and oversee a lasting economic recovery.

Problems with the Western Approach

The NGOs in question tend to take one of two approaches to helping the AANES. Some development agencies funded by the United States and European Union work directly in the areas they assist, with local residents and authorities generally welcoming their help. Yet other NGOs work mainly from distant offices on the border (Peshkhabur) or further inside Iraq (Erbil), making occasional, short field visits at most. These organizations tend to subcontract much of the work to local NGOs or companies without any real assessment of needs or supervision, resulting in substantial mismanagement and corruption. For example, forged invoices and quotes are common, workers are often extorted when they sign employment contracts, and some projects are unnecessarily duplicated just so organizations can justify their budgets.

Although the decision to operate remotely can be partly explained by the security conditions, it appears to be compromising the effectiveness of the hundreds of millions of dollars poured into the AANES. The situation is all the less tolerable because the area’s needs are enormous, and rampant mismanagement has begun to accentuate local frustration toward Western aid policies.

Another issue is that Western governments have been content with emergency interventions instead of undertaking a real reconstruction policy involving major infrastructure projects. Admittedly, the AANES has no official recognition at the international level, which limits the modes of intervention. But preventable external factors have played a major role as well. Russia has repeatedly vetoed UN efforts to reauthorize direct cross-border aid from Iraq, forcing many agencies to work through the Assad regime in Damascus. And in the north, Turkey has continued its habitual cross-border bombing and shelling in order to destabilize the area, scare the population, and discourage investment. In Kobane, for example, real estate developers have stopped most construction since October 2019 for fear that the city will suffer the fate of Turkish-controlled Afrin or Ras al-Ain.

To be sure, some measures indicate that the economic situation in the AANES is better in many respects than that of Syria’s regime-held areas. Yet this does not mean the situation is good or sustainable. Even the temporary fixes could unravel quickly in the event of a new Turkish offensive, prolonged border closure, worsening drought conditions, or any number of other scenarios. And while having U.S. troops on the ground is a sine qua non for the AANES, their presence is not sufficient to ensure its survival. More development assistance, and a strategic rethinking of how and where it is provided, are essential to offset the destabilizing measures coming from Turkey and the Assad axis, which have stoked local economic problems and a crisis of confidence in the autonomy project.

Conclusion

Many residents of the AANES had high hopes that Joe Biden’s election would signal an upsurge in U.S. involvement after the disastrous American withdrawal from the Turkish border in October 2019. Unfortunately, the administration has so far been content with a minimal-service approach to Syria. Following the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, authorities in the AANES are afraid they might suffer the same fate—a fear exacerbated by the departure of special envoy David Brownstein last December after less than a year in that post. He was reportedly very well-liked and had given many assurances about the presence of American troops. Besides his personal attributes, rapid turnover of political staff can be particularly deleterious to relations with officials in the Middle East, and the AANES is no exception. If Western governments really want to support autonomy in northeast Syria, they will need to reassure locals with a long-term policy that simultaneously yields immediate concrete benefits.

The most urgent elements of such a policy are clear. The international coalition should firmly declare that its troops will not leave the AANES until Damascus agrees to a political deal on autonomy—and even then only with serious guarantees. Otherwise, authorities in the northeast may feel compelled to seek Russian or even Iranian protection against Turkey. Currently, Russian troops in the area are holed up in makeshift bases and only come out in convoys accompanied by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). A long-term U.S. presence would accentuate the isolation of these Russian forces and perhaps even contribute to their departure, especially if the SDF no longer believe they need Moscow. For that to happen, however, Washington and its allies would need to convince Turkey to cease its cross-border threats and evacuate the zone between Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain, if only so the AANES can regain some geographical coherence.

On the economic level, Western support must go beyond simply trying to maintain a standard of living above that of the beleaguered regime zone. Real autonomy in the northeast requires a real reconstruction policy.

Fabrice Balanche is an associate professor at the University of Lyon 2 and an adjunct fellow with The Washington Institute.