- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

Introducing the Hezbollah Worldwide Map and Timeline

This multimedia tool -- easily the most comprehensive of its kind -- illuminates the full range of Hezbollah's activities, from travel routes and aliases to larger themes related to the organization's founding, development, and relationship with key state sponsors.

Dedicated in Memory of Mary Kalbach Horan

Lebanese Hezbollah is a global, multifaceted organization, engaged in a wide range of endeavors, including overt social and political activities in Lebanon, military activities in Lebanon, Syria, and throughout the Middle East, and covert militant, criminal, and terrorist activities elsewhere around the world. While Hezbollah has a vested interest in publicizing its political, health, education, and other social welfare programs—which it does through its television, radio, Internet, and social media platforms—the group goes to even greater lengths to conceal its militant and criminal actions. “Due to the secretive nature of [Hezbollah’s terrorist wing], it is difficult to gather information on its role and activities,” an Australian government report acknowledged in 2003.1 As one Hezbollah handler made clear to the U.S.-based operative he was supervising, the “golden rule” of Hezbollah’s terrorist units is, “the less you know about the unit, the better.”2 Indeed, such compartmentalization is a cornerstone of Hezbollah’s operational security training.

Moreover, when information about Hezbollah’s covert and illicit activities does come to light, it typically happens in small bursts—a fact here, a snippet there. To date, there is no single repository of the collected, open-source information about Hezbollah’s worldwide activities. The lack of transparency and available information has severely hampered the emergence of an informed public debate about the totality of Hezbollah’s activities.

After nine years of research, I published my book Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God (Georgetown University Press, 2013). The following year, an updated paperback edition was released, with a new afterword detailing the group’s more recent involvements in Syria and its role in several terrorist plots since the initial publication date. Since then, I have continued to research and write about Hezbollah’s worldwide activities, focusing on the group’s terrorist operations, weapons procurement, money laundering, narco-trafficking, and other illicit financial schemes. I have also observed and written about the group’s metamorphosis from a local militant organization dedicated to improving its position in Lebanon, and destroying Israel next door, to a regional militia interested in fighting Iran’s wars, training Iran’s other proxies, and carrying out militant activities far afield from and unrelated to both Lebanon and Israel.

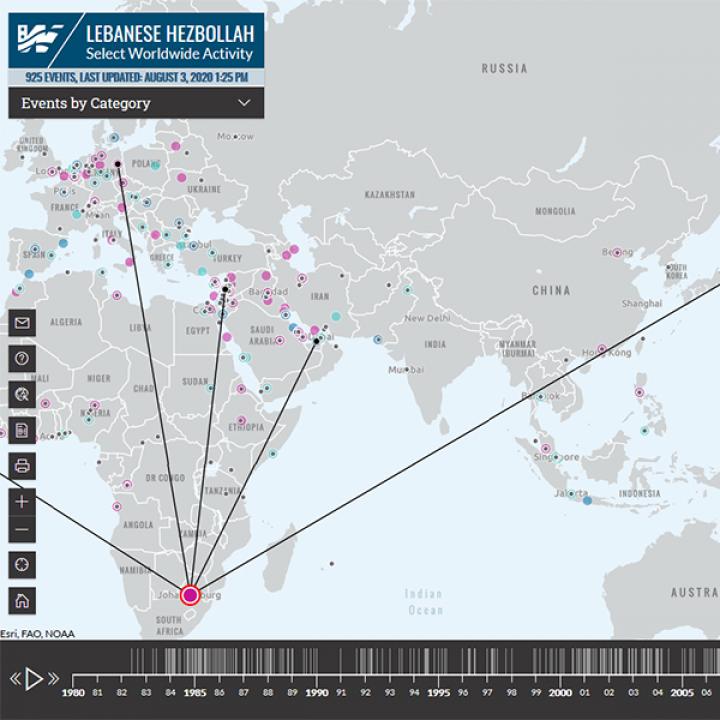

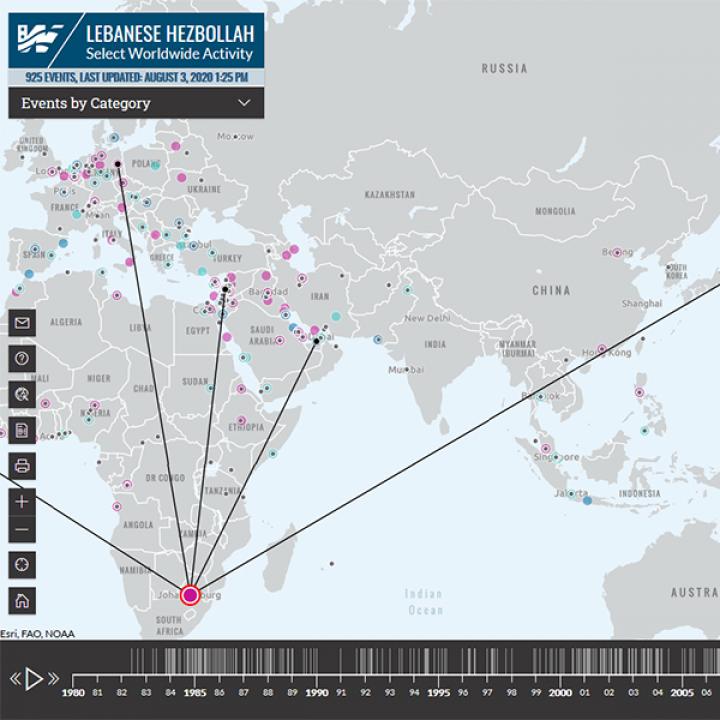

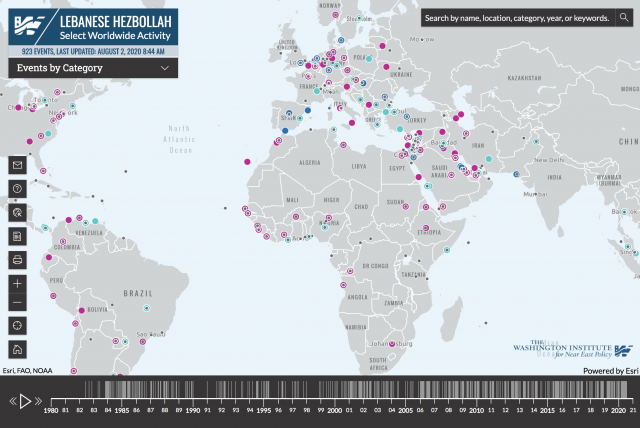

Using research from my book and subsequent work as a starting point, I decided to build an interactive map and timeline of Hezbollah activities around the world, from its foundation in the early 1980s until today. This is intended to be an iterative project; although we are launching with approximately a thousand entries, we plan to continue to add new entries, source documents, and features after the launch. Since the product will change over time, we have also included a “counter” informing users of the cumulative number of entries in the map and the time of the latest update, available in the upper left-hand corner.

This map is fully interactive and is searchable by category, location, timeline, and text keywords. Each entry includes photographs or videos, a summary of the event, geographic and/or thematic linkages to other related entries in the map, as well as primary-source documents. The tool is already, far and away, the largest repository of open-source documentation on Lebanese Hezbollah, comprising declassified government reports, court documents, congressional testimony, and research reports.

Origin Story

Although I have worked on the issue of Hezbollah terrorism since the 1990s, the Hezbollah map’s origins date to spring 2003. As I noted in the opening of my book, I have attended many conferences and meetings with officials from various governments in which having an informed discussion about Hezbollah’s covert enterprises was rendered virtually impossible by the dearth of publicly available material on the group’s covert activities. This conundrum came to a head for me a couple of years after I left the FBI, at a fairly typical Washington DC policy conference:

In May 2003 I participated in a conference for current and former U.S. law enforcement and intelligence personnel on Lebanon. Sponsored by the U.S. government and featuring speakers from the United States and Lebanon, each of the conference panels was chaired by a U.S. official. Strikingly, when participants on several panels insinuated that Hezbollah had never engaged in an act of terrorism or that there was no such person as Imad Mughniyeh (Hezbollah’s late operations chief)—both concepts being American or Israeli fabrications—the U.S. officials chairing the respective panels said nothing. The issue was put to rest once the session was opened up to questions from the audience, but the experience left me convinced of the need for a serious study focusing on Hezbollah’s clandestine activities worldwide to complement the already rich literature on the party’s overt activities in Lebanon.3

This seed of an idea led to a multiyear undertaking, conducting interviews around the world, collecting court documents and government reports, and otherwise building a collection of information about Hezbollah’s covert activities. Once the manuscript was ready, the hardworking team at Georgetown University Press went to work copy editing, laying out the pages, and printing the book. These efforts took place in the wake of a thwarted Hezbollah plot in Cyprus, a Hezbollah bus bombing in Bulgaria, Hezbollah’s entry into the Syrian civil war, and a heated debate among European Union member states over whether or not to designate Hezbollah as a terrorist group at all, partially, or in its entirety. In July 2013, the EU chose the second option, designating only Hezbollah’s military wing, but in the months leading up to that decision I made several trips to Brussels and other EU capitals to meet with officials, speak at academic and policy conferences, and testify before the European Parliament, at each of these forums stressing the merits of designating Hezbollah in its entirety.

Aside from concerns that designating Hezbollah would either prevent Europeans from being able to engage with Lebanese politicians, that it would destabilize Lebanon, or that Hezbollah would carry out reprisal attacks targeting Europeans, two primary themes arose repeatedly in these meetings and events.4

First, while academics and officials alike were aware of Hezbollah’s political and social activities in Lebanon, and were generally cognizant of the group’s role in terrorist attacks in Lebanon, Argentina, and Europe in the 1980s and early 1990s, few people demonstrated any understanding of Hezbollah’s ongoing terrorist and militant activities, and they showed still less awareness about the group’s organized criminal enterprises. I found myself providing officials with details—and sometimes documents—about major cases that occurred in their respective countries, of which they previously knew nothing. In one telling moment, the director-general of the foreign ministry of an EU member state complained that his country was ignorant about Hezbollah because U.S. officials did not share their information. But he then quickly declined my offers to provide him reports on Hezbollah activities produced by his own country’s intelligence services and to connect him with the FBI legal attaché at the U.S. embassy in said country (who, as it happens, previously served as the Iran/Hezbollah unit chief at FBI headquarters).

Second, when officials did acknowledge that their governments held some information about Hezbollah’s terrorist activities, they were unable to use that information for any public purpose—such as a trial in court or a designation by policymakers—because the information they had was classified. “Where am I supposed to get such information?” an official in another European capital asked me. If only there were an open-source collection of reliable information about Hezbollah’s worldwide activities, this official lamented.

My book filled this gap nicely, especially once Hurst Publishers bought the European distribution rights. Still, the book’s Hezbollah chronicle ended in 2013 (2014 for the paperback). Furthermore, the book’s plethora of information is a doubled-edged sword, important for a nuanced and encyclopedic understanding of Hezbollah, but also potentially overwhelming and hard to digest. This dilemma was the topic of extensive conversations—or, to be more precise, one often-interrupted but ongoing conversation—between me and The Washington Institute’s publications director, Mary Horan. I was wary of investing the time and energy necessary to build this map, but Mary eventually convinced me of its potential. Mary could see the map long before I could, and it is her vision that is reflected in this product. Thus took root the idea of converting the archive of documents I have collected regarding Hezbollah’s global activities into an interactive, user-friendly, open-access multimedia tool.

Three more years passed, during which I continued to research, collect information, and write about Hezbollah’s global activities. Then, in 2017, the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) released an interactive timeline, “Lebanese Hizballah: Select Worldwide Operational Activity, 1983–2017.”5 The NCTC timeline includes forty-nine entries, documenting Hezbollah activities all around the globe, but it is limited to strictly operational items (attacks, attack planning disrupted, and military adventurism) and excludes many other cases of Hezbollah operations.

The U.S. Department of State later released a one-page graphic depicting ten select Hezbollah operational activities in Europe from 1983 through 2017 (a second page listed eleven cases of Iranian operational activity in Europe from 1979 to 2018).6 This, too, excluded a great many cases of Hezbollah operations in Europe over the given time period.

Taken together, the NCTC and State Department lists of Hezbollah activities left out far more than they included. The reason for this selectivity, I found out when I inquired, was not that the experts in these agencies were unaware of the full scope of Hezbollah’s global terrorist activities, but that concerns about protecting classified information limited what they could report. And so the decision was, in a way, made for me; if the government could not declassify sufficient information to give a full picture of Hezbollah’s activities, then I would have to make my own collection of unclassified and declassified materials available in a more accessible format.

This Lebanese Hezbollah Select Worldwide Activity Interactive Map and Timeline aims to realize this goal. Now, with this tool, diplomats, policymakers, and pundits can see the totality of Hezbollah activities, not just those the group wants the public to know about. Now, a body of unclassified material—some unclassified from the outset, some originally classified but now declassified—is available for use in public debates and government actions, without fear of putting intelligence sources and methods at risk.

The Map

Before explaining the tool’s capabilities, it is important to note its key limitation, which arises from its being a collection of open-source materials documenting the covert activities of an illicit enterprise. While this is by far the largest collection of information and documentation about Hezbollah activities around the world, it is by no means an exhaustive collection—it includes just those activities recorded in unclassified sources. Users should be careful not to draw conclusions based on the map about what Hezbollah did or did not do at a given time, or in a given situation, since the information here is by definition incomplete. Users should also be careful not to give more weight to incidents about which there is more unclassified information versus those with less—the fact that we know more about one incident does not make it more significant than another with less publicly available information.

Click on the image above to visit the full interactive map and timeline.

That said, this resource is vast. This is not only because of the number of entries included, and the full range of activities covered in these entries, but because of the large number of underlying documents included (elaborated later) and its nature as a “living” project, to be updated as more information and documentation becomes available.

The information here sheds much-needed light on the full geographic and temporal range of Hezbollah activities and also addresses an array of themes related to the group’s history, modus operandi, relationship to key sponsors such as Syria and Iran, and so forth.

Consider a few examples of thematic takeaways:

- Founding and development of Hezbollah. In its early years, 1982–85, before the group publicly announced its existence with its 1985 Open Letter, several groups aligned themselves together under the name “Hezbollah.”7 Intelligence officials had a hard time understanding the nature of the relationship between and among these groups, as declassified CIA documents make clear.8

- Islamic Jihad Organization as Hezbollah. Declassified CIA documents, the 2006 report by Argentine prosecutor Alberto Nisman, and other reports make clear that intelligence officials around the world understood very early on that Hezbollah used several “cover names” for its operations, the most important and popular being Islamic Jihad Organization (IJO).9 Officials clearly understood even then that the IJO was not a separate entity from Hezbollah, but rather the group’s operational component.

- Relationship with Syria. Today, Hezbollah and the Syrian regime are close allies, with Hezbollah backing Bashar al-Assad in the Syrian civil war.10 But there were times in the 1980s, for example, when Syrian forces openly fought Hezbollah.11

- Relationship with Iran. Hezbollah has always had an intimate relationship with Iran, but the nature of that relationship has fluctuated. At times, Hezbollah was under near complete command of Iran, while at others it was not.12 Today, in large part as a result of their joint defense of the Assad regime in the Syrian civil war, Iran and Hezbollah have an especially close operational relationship.13 Regardless, Iran gives Hezbollah significant latitude and independence when it comes to decisions about the latter’s activities in Lebanon.

- Unitary nature of Hezbollah. There are no distinct wings within Hezbollah, as Hezbollah officials remind observers time and again.14 Governments may choose to conjure up distinctions among the group’s social, charitable, political, military, terrorist, and criminal activities, but Hezbollah itself makes no such distinctions.

Beyond elucidating broad trends, the tool reveals little-known cases, such as that of the Hezbollah suicide bomber who blew up Alas Chiricanas Airlines Flight 00901 on July 19, 1994,15 and previously undisclosed cases, such as the joint operation Hezbollah and Palestinian Islamic Jihad plotted (but never carried out) in late 1990 targeting Jewish emigres from the former Soviet Union congregating at a Warsaw synagogue.16

The map also offers new information on more granular logistics, like the travel routes Hezbollah operatives took into and out of Bulgaria in July 2012 for the Burgas bus bombing,17 the name of the Lebanese-French professor who Cypriot police say bought the safe house where Hezbollah was storing ammonium nitrate ice packs for the production of explosives,18 and the true name of “Fadi Kassab,” the Hezbollah handler who oversaw operatives involved in terrorist activities in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Canada, and the United States.19

Much attention has gone into how to build this map, from the macro questions of design and available features to the micro questions surrounding the temporal, geographic, categorical, and other coding decisions related to individual entries. Here is how we addressed several such issues:

1. Spellings (of Hezbollah and other names)

In this map, we generally adopt the spellings used in government documents. Occasionally, different government agencies spell Arabic names differently. In these instances, we use the spelling from the agency referenced (i.e., an entry regarding an individual’s Treasury Department designation might be spelled one way and the entry pertaining to the State Department–issued Rewards for Justice announcement for the same individual might use another). Generally, we use the spelling “Hezbollah” to refer to the terrorist group. However, when quoting other sources, we maintain their respective spellings of the organization. Fortunately, the search box takes into account all aliases and transliterations given by Treasury Department and other news reporting.

2. Document repository, primary sources, and page numbers

We try to include primary-source documentation wherever possible. The tool includes criminal complaints, indictments, trial testimony, FBI posters, Treasury Department designations, State Department Rewards for Justice announcements, government press releases, and several research reports from nongovernmental organizations, used with their permission.

In some instances, events reflect author interviews with intelligence or government officials that cannot be reproduced. In these scenarios, the relevant page from Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God is included, with the generous permission of Georgetown University Press. To access footnotes with the original source or learn more about Hezbollah overall, see the full edition of the book.

A related note about navigating documents: the page numbers included in the Documents section of each entry reflect where quotations or material relating to the given event can be found. We reference the original page numbers, not those later produced in the PDF (unless the original lacks page numbers).

3. Dates for incidents

Because this tool functions as a map as well as a timeline, each event is linked to both a date and a location. When the specific date of an event is unavailable, we use the date of the report or statement in which the event is mentioned. For example, when a Treasury Department designation mentions militant activity that occurred in a particular year, the activity will appear on that year in the timeline.20 However, if the designation does not identify the time or span of that activity, the year used is that of the designation itself.

When the only information available is of the year or decade in which the activity took place, the entry will appear at the earliest possible date on the timeline (i.e., January 1, 1990, if 1990 is the information known), but the date in the text box constitutes only the confirmed information (i.e., 1990).

Users can limit results to a specific time period by adjusting the timeline at the bottom of the screen. To view all events from a particular year, users can click on the specific year in the timeline and browse the drop-down list of the year’s events.

4. Dates for judicial actions

We try to maintain consistency in our indexing of judicial actions. Entries reflect the earliest known mention of an individual’s encounter with law enforcement. Whenever possible, judicial actions are categorized as arrests. However, when an individual(s) is indicted in absentia or the date of arrest is unknown, the entry is framed around his or her indictment. Information pertaining to the trial, verdict, and sentencing is included in this same entry and will be updated to reflect new information

When an extradition is carried out quickly after an arrest, information about the extradition is included in the same entry. For example, Moussa Ali Hamdan was indicted on November 24, 2009, in the United States, but was not arrested until June 15, 2010, in Paraguay. He was taken into U.S. custody and extradited on February 24, 2011. Due to the time and location gaps between indictment and arrest/extradition, we have included two separate entries on Hamdan’s trial.21 When there are several entries for related cases, such as someone’s arrest and extradition, the associated entries will be listed in the “See Also” section.

When an individual is arrested on nonterrorism charges but has links to Hezbollah, we note this distinction in the text.22 Apprehension, administrative detention, and other custodial actions are referred to accordingly, but may still be categorized as Arrests for ease of searchability.23

5. Cross-coding of entries, and colored dots on the map

The categories filter, on the map’s upper left-hand corner, allows the user to search by category. Clicking on a category or subcategory will produce a drop-down menu of events fitting the category, and will also limit the events appearing on the map itself. The user may notice that events of multiple colors remain even when a specific category (color) is selected. This is not an error but rather reflects the cross-coding of some events under multiple categories. For example, the Treasury Department designation for Saleh Mahmoud Fayad is coded primarily as a designation under “Counterterrorism Actions” (magenta) but also as a case of “Finance” and of “Travel” under “Finance and Logistics” (aqua); this is because Fayad serves as a Hezbollah counterintelligence operative and fundraiser, as well as a courier between South America’s Tri-Border Area and Lebanon. As such, his entry will appear as a magenta point on the map even when “Finance and Logistics” or the constituent categories “Finance” or “Travel” (aqua) are selected.24

6. Searching by country

The “Search by Country” function allows users to narrow their search to events involved with or taking place in a specific country. After a user selects a country, a drop-down will appear with a list of related events, and only relevant dots will appear on the map. The user will likely notice that events still appear in multiple countries on the map. The remaining events include cases linked by association. For example, if a user selects Italy, a dot will also appear in Switzerland. This is because after Hussein Hanih delivered explosives and arming devices to an Islamic Jihad Organization cell in Italy, Swiss police arrested him at the Zurich airport, according to the entry “Hussein Hanih Atat Arrested for Transporting Explosives.”

7. Approach to geolocation

Events are geolocated at the most relevant spot. When town/city information is not available, entries are geolocated in the capital of the country where the event occurred. Although capitals serve as both actual locations of an event and stand-ins for an undetermined in-country location, the text description indicates whether the action actually took place in the capital (e.g., Beirut, Lebanon vs. Lebanon). Similarly, when publicly available information links an event to a broader continent or region, the event is geolocated at a specific city (e.g., Beijing for Asia, Brussels for Europe, Sacramento for California).

Entries for statements or reports are generally geolocated as described therein, not at the location of publication. For example, CIA Report Cites Saudi and Jordanian Intelligence on Hezbollah Links to Khobar Towers Bombing is in Saudi Arabia; CIA Report Notes Hezbollah Threat to U.S. Personnel in Lebanon is in Lebanon; CIA Report Warns Syria Underestimates Hezbollah is in Syria; and so on.25 Only for broader statements that omit mention of a region do the entries appear at the location of delivery or publication.26

8. Gray points and “spider lines” to demonstrate Hezbollah’s geographic breadth

This map is intended to demonstrate the geographic breadth of Hezbollah’s activities, which span six continents. As CIA analysts articulated in 1987, “Like their Iranian brethren, Hizballah maintains that the Islamic Revolution must be a worldwide phenomenon and cannot be confined within the boundaries of a singular country.”27 Hezbollah, they noted, had “aspirations to become a sponsor of worldwide Islamic fundamentalism.”28 The terrorist group has long since fulfilled and continues to actualize these ambitions.

In order to demonstrate Hezbollah’s international linkages, we rely on two functions: gray points and spider lines. Gray points are placed on the map wherever ancillary Hezbollah activity occurred related to another event on the map. The gray point suggests some relationship between its location and another location/event on the map. For example, a gray point will appear in Moscow because several events mention either Russian nationals or Russia, the Soviet Union, or Moscow in-text.29

Gray points are superimposed on colored points when events occurred at this location and others are associated with this location (e.g., see Lima, Peru, to which the Treasury Department Designation of Muhammad Ghaleb Hamdar is pinned but the Treasury Designation of Samuel Salman el-Reda is associated).30

Spider lines are used to represent geographic linkages mentioned within an entry. When directional flows of funds or specific travel itineraries are known, these lines are configured accordingly, moving from location to location rather than each radiating outward from the central location of the event.

9. Decoupling dots from activity volume

The visual map can be misleading in that a dot does not necessarily reflect the amount of activity at a single location. Indeed, any location where one or many events occurred receives a single colored dot. In order to more accurately conceptualize the extent of Hezbollah activity by location, users must click on the location’s dot, which will generate a list of all colocated events.

10. Combining filters

The map allows users to further narrow results by employing multiple filters. For example, to view all Hezbollah plots and attacks in the Netherlands since 2000, users can select Netherlands from the country filter, narrow the timeline to 2000–21, and select the Plots and Attacks category.

11. Links and distinctions between Iran, the IRGC Qods Force, and Hezbollah

As one of Tehran’s foremost proxies, Hezbollah works closely with Iran and the Qods Force of its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, particularly to train Hezbollah recruits and other Shia fundamentalists. Reports have repeatedly noted this “intimate relationship.”31 The training of recruits is a particular area of overlap. A few years after Hezbollah’s founding, the CIA noted that Revolutionary Guards based in the Beqa Valley “are often co-located with Hizballah elements and share the same communications and support network.”32 Hezbollah has also carried out several operations in cooperation with Iranian agents, as in the bombing of the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina Jewish community center in 1994, and sometimes in concert with other Iranian proxies, as in the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia.33 More recently, the January 20, 2007, attack on the Karbala Provincial Coordination Center, in which five U.S. soldiers were killed and three were injured, was a joint operation involving Iranians, Iraqi proxies, and Hezbollah.34 According to documents seized in a U.S. raid, the Qods Force had gathered detailed information on U.S. soldiers in Karbala. Iraqi Shia Qais al-Khazali and his brother Laith al-Khazali, as well as Hezbollah veteran Ali Musa Daqduq, were involved in planning the attack.35

Also complicating attribution are conflicting claims of responsibility by groups using Hezbollah cover names or acting under its umbrella (discussed elsewhere). As such, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between Iran- and Hezbollah-run operations. This map includes only those incidents in which Hezbollah was operationally involved, with or without Iranian support. Events such as a January 2012 plot targeting two Israeli Chabad emissaries, a rabbi, and a teacher at the Or-Avner Jewish school in Azerbaijan,36 or the January 1984 bombing of a French cultural center in Lebanon,37 are omitted for lack of evidence connecting them to Hezbollah. It should be noted that some Treasury Department designations or intelligence reports pertaining to non-Hezbollah officials are included in the map, but the focal point for these entries is the Hezbollah-related activity mentioned therein.38

12. Recent developments

This map is constantly being updated as documents are declassified and new events unfold. The upper left-hand corner lists a running tally of entries, and clicking “Last Updated” reveals a drop-down of the most recently added events in reverse chronological order. In addition, the Hezbollah News widget at the left is frequently updated with news about Hezbollah activities from outlets around the world. Should users want to read more about overall trends or impressions from experts, the Hezbollah Analysis widget includes an updated list of recently published analyses.

Acknowledgments

This map would never have seen the light of day were it not for the efforts of a great many people.

I have had the benefit of exchanging ideas and checking facts with numerous subject matter experts, all of whom wish to remain anonymous, but to whom I am eternally grateful. You know who you are, and you have my deepest thanks and appreciation. I have also benefited from traveling the world and meeting the policymakers responsible for Hezbollah issues, the police officers and case agents overseeing Hezbollah investigations, the prosecutors building their criminal cases, and the analysts and intelligence professionals covering Hezbollah. Thank you all for your time and the confidence you have placed in me by agreeing to meet. I am especially grateful to the many people who have helped me secure documents that I can now share with a wider audience.

The design and technical teams at International Mapping have been fantastic partners. They are true professionals and a pleasure to work with. I am grateful beyond words to The Washington Institute’s publications team, led first by Mary Kalbach Horan and now by Maria Radacsi. Jason Warshof is an editor extraordinaire, Scott Rogers has been a wise sounding board throughout the process of creating the map, and the Institute’s communications team led by Jeff Rubin has been supportive from the outset.

The Washington Institute is a fabulous intellectual community, and I thank all my colleagues for their patience and counsel. This map is better for their feedback. I am particularly indebted to Katherine Bauer and Aaron Zelin, the two other legs of the tripod that is the Institute’s Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence.

A project like this is only possible if leadership buys into the idea, and I am grateful for the support and encouragement of the Institute’s leadership, especially Executive Director Robert Satloff and Director of Research Patrick Clawson.

But at the end of the day, the nuts and bolts of this product came together only due to the tireless efforts of research assistants and interns in The Washington Institute’s Reinhard Program. Avichai Bass took on the responsibility of organizing the original batch of research, which was a monumental task. Samantha Stern then assumed the organizational role, becoming the map’s overall project manager, followed by Lauren Fredericks, who continued maintaining and updating the map. It is no exaggeration to say the map would not be what it is today, or have been ready for launch on time, were it not for Sam’s tremendous dedication and perseverance. Special thanks to research interns Hannah Labow and David Patkin, who made significant contributions to the map’s production.

Finally, the financial support of key Washington Institute donors makes significant undertakings such as this project possible. It is a tremendous honor to be named the Institute’s Fromer-Wexler Fellow, and to direct the Jeanette and Eli Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence. There are certain people one is better for having met, and the Fromers, Wexlers, and Reinhards are just such people. Thank you, for everything.

Dr. Matthew Levitt

Washington DC

Notes

1 See map entry “Australia Designates Hezbollah’s ESO,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=306.

2 See map entry “Fadi Kassab Acts as Ali Kourani’s Handler,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=386.

3 Matthew Levitt, Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God (Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2013), xiii, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/media/4184.

4 On the first few concerns, see Matthew Levitt, “Debating the Hezbollah Problem,” ICSR Insight, January 22, 2018, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/debating-the-hezbollah-problem.

5 See “Lebanese Hizballah: Select Worldwide Operational Activity, 1983–2017,” U.S. National Counterterrorism Center, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 2017, at map entry “U.S. National Counterterrorism Center Releases ‘Interactive Timeline of Lebanese Hizballah: Select Worldwide Operational Activity, 1983–2017,’” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=982.

6 “Lebanese Hizballah: Select Europe-Based Operational Activity, 1983–2017,” U.S. Department of State, July 5, 2018, at map entry “U.S. Department of State Publishes ‘Lebanese Hizballah: Select Europe-Based Operational Activity, 1983–2017,’” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=983.

7 See map entry “Hezbollah Announces Its Existence in Open Letter,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=981.

8 See, e.g., “Terrorism Review,” Central Intelligence Agency, November 18, 1985, 11–15, at map entry “CIA Report Notes Hezbollah’s Growth into an Organized Network,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=126; “Terrorism Review,” Central Intelligence Agency, April 8, 1985, 3–7, 19–22, at map entry “CIA Report Notes ‘Wild, Wild West Beirut,’” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=93.

9 See, e.g., “Beirut as a Terrorist Center,” Central Intelligence Agency, January 1987, 8, at map entry “CIA Report Notes Hezbollah Use of Cover Name Islamic Jihad in Claims of Responsibility,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=811; “Iranian Terrorist Activities in 1984,” Central Intelligence Agency, 1984, 2–3, at map entry “CIA Report Identifies Islamic Jihad Cover Names,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=804.

10 See, e.g., “Treasury Sanctions Hizballah Leaders, Military Officials, and an Associate in Lebanon,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 21, 2015, at map entry “Hassan Nasrallah and Mustafa Badreddine Meet Weekly with Bashar al-Assad to Discuss Strategic Coordination,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=471; “Iran Military Power: Ensuring Regime Survival and Securing Regional Dominance,” Defense Intelligence Agency, August 2019, at map entry “DIA Report Details Hezbollah Training in Syria,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=721.

11 See, e.g., “Terrorism Review,” Central Intelligence Agency, November 18, 1985, 19–20, at map entry “CIA Report Warns Syria Underestimates Hezbollah,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=130; “Terrorism Review,” Central Intelligence Agency, December 21, 1987, 12–13, at map entry “CIA Report Describes Tense Hezbollah-Syria Relationship,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=894.

12 See, e.g., “Terrorism Review,” Central Intelligence Agency, November 18, 1985, 11, 17–19, at map entry “CIA Report Notes Hezbollah’s Increasing Independence,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=129; “Iranian Terrorist Activities in 1984,” Central Intelligence Agency, 1984, 3–5, at map entry “Iran Recruits and Trains ‘Hizballahi’ Fighters,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=802.

13 See, e.g., “Treasury Targets Procurement Networks and 31 Aircraft Associated with Mahan Air and Other Designated Iranian Airlines,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, May 24, 2018, at map entry “Treasury Department Designates Mahan Air Procurement Network,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=659; “Summary of Terrorism Threat to the U.S. Homeland,” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, January 4, 2020, at map entry “DHS Report Warns of Iranian Threat to Homeland,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=750.

14 See, e.g., “Treasury Targets Iranian-Backed Hizballah Officials for Exploiting Lebanon’s Political and Financial System,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 9, 2019, at map entry “Mohammad Hassan Raad and Wafiq Safa Maintain List of Hezbollah Members for Foreign Travel,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=708; “Treasury Targets Iranian-Backed Hizballah Officials for Exploiting Lebanon’s Political and Financial System,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 9, 2019, at map entry “Amin Sherri Threatens Bank Officials,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=707.

15 See map entry “Alas Chiricanas Airlines Flight 00901 Destroyed in Suicide Attack,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=18.

16 See “Iran: Enhanced Terrorist Capabilities and Expanding Target Selection,” Central Intelligence Agency, April 1992, 12, at map entry “Warsaw Synagogue Attack Planned,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=182.

17 See map entry “Mohamad Hassan El-Husseini Travels to Bulgaria,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=495; map entry “Meliad Farah Travels to Bulgaria,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=486; map entry “Hassan El Hajj Hassan Travels to Bulgaria,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=494; map entry “Hassan El Hajj Hassan and Meliad Farah Travel through Bulgaria,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=493; map entry “Hassan El Hajj Hassan and Meliad Farah Flee to Lebanon,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=496.

18 See map entry “French-Lebanese Professor Buys Hezbollah Safe House in Cyprus,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=437.

19 See map entry “Fadi Kassab Acts as a Bulgarian Handler,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=388; map entry “Fadi Kassab Acts as Hossam Yaacoub’s Handler,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=389; and map entry “Fadi Kassab Acts as Ali Kourani’s Handler,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=386.

20 See, e.g., map entry “Samuel Salman el-Reda Travels to Colombia,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=215; map entry “Saleh Mahmoud Fayad Travels to Lebanon,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=237; and map entry “Khalil Yusif Harb Manages Hezbollah Operations in Eastern Mediterranean,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=248.

21 See map entry “Hassan Hodroj, Dib Hani Harb, Moussa Ali Hamdan, and Hasan Antar Karaki Indicted,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=434; and map entry “Moussa Ali Hamdan Arrested and Extradited,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=465.

22 See, e.g., map entry “Ibrahim Ahmadoun Arrested,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=578; map entry “Kassim Tajideen Arrested,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=628; map entry “Mustafa Abu Darwish Arrested,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=663; and map entry “Jeroen van den Elshout Arrested,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=844.

23 See, e.g., map entry “Suspected Pakistani Hezbollah Operative Detained,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=716; and map entry “Heba al-Labadi Detained,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=724.

24 See, e.g., map entry “Treasury Department Designates Saleh Mahmoud Fayad,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=360.

25 See map entry “CIA Report Cites Saudi and Jordanian Intelligence on Hezbollah Links to Khobar Towers Bombing,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=902; map entry “CIA Report Notes Hezbollah Threat to U.S. Personnel in Lebanon,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=92; and map entry “CIA Report Warns Syria Underestimates Hezbollah,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=130.

26 See, e.g., map entry “FBI Director Robert Mueller Advises ‘Vigilance’ with Respect to Hezbollah,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=319; map entry “FBI Director James Comey Warns that U.S.-Based Hezbollah Subjects Could Attempt Attacks,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=289; map entry “CIA Director George Tenet Warns of Hezbollah’s Advanced Capability,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=304; and map entry “NCTC Deputy Director Warns of Iran-Hezbollah Relationship,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=742.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid., 13.

29 See, e.g., map entry “Ali Fayyad Arrested,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id= 550; map entry “Budapest Airport Attack Planned,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=183; map entry “Warsaw Synagogue Attack Planned,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=182; and map entry “Soviet Diplomats Kidnapped,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=113.

30 See map entry “Treasury Department Designates Muhammad Ghaleb Hamdar,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=609; and map entry “Treasury Department Designates Samuel Salman el-Reda,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=712.

31 “Iranian Involvement with Terrorism in Lebanon,” Central Intelligence Agency, June 26, 1985, 2, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP87T00434R000300240059-5.pdf.

32 Ibid., 1.

33 See map entry “Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina Community Center Bombed,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=196; and map entry “Khobar Towers Bombed,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=214.

34 See map entry “Karbala Provincial Center Targeted in Attack,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=367.

35 See, e.g., map entry “Ali Musa Daqduq al-Musawi Arrested,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=371.

36 Barak Ravid, “Azerbaijan: Iranian, Hezbollah Operatives Arrested for Plotting Attack against Foreign Targets,” Haaretz, February 21, 2012, https://www.haaretz.com/1.5188659; Marcy Oster, “Azerbaijan Arrests Terror Suspects Linked to Hezbollah, Iran,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, February 21, 2012, https://www.jta.org/2012/02/22/global/azerbaijan-arrests-terror-suspects-linked-to-hezbollah-iran.

37 “Terrorism Review,” Central Intelligence Agency, February 2, 1984, 2, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP84-00893R000100350001-2.pdf.

38 See, e.g., map entry “Treasury Department Designates Iranian Committee for the Reconstruction of Lebanon,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=445; map entry “Treasury Department Designates Iranian Ministry of Intelligence and Security,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=481; and map entry “Treasury Department Designates Abdul Reza Shahlai,” https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/hezbollahinteractivemap/#id=406.