The IAEA’s new uranium revelations are amplifying concerns about a potential multifront war between Israel and Iran.

In a worrying reversal of policy amid war in the Middle East, Iran has tripled its production of high-enriched uranium (HEU) after several months of reduced output. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) offered rare public remarks on the matter on December 26, confirming to various media outlets that Iranian nuclear facilities are producing about 9 kilograms of 60% HEU per month instead of the previous 3 kg.

Iran already has enough 60% HEU for three nuclear weapons if the material were further enriched using a short two-week process (see below). Gleaned from plants at Natanz and Fordow, the extra production adds to this stockpile of potentially weaponizable material. Iran denies it is seeking nuclear weapons but has no other use for such large quantities of such highly enriched uranium.

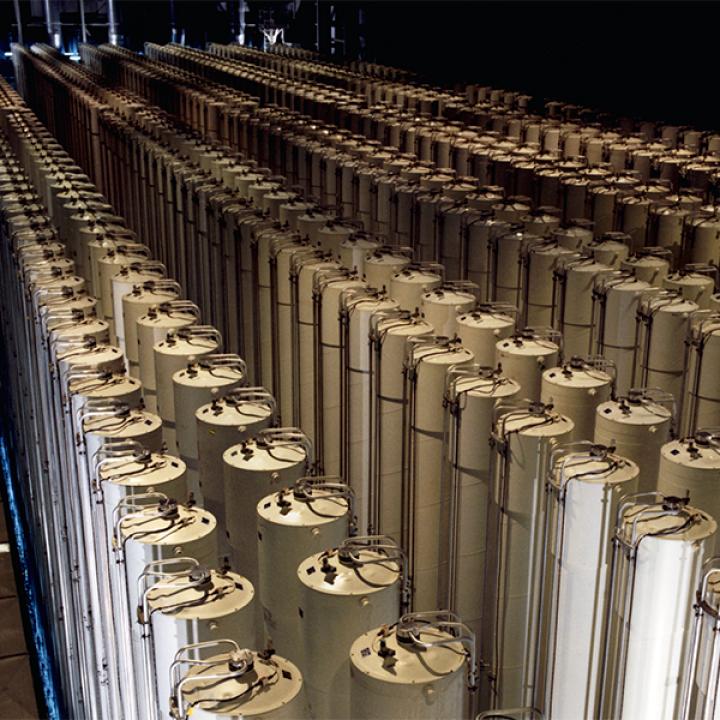

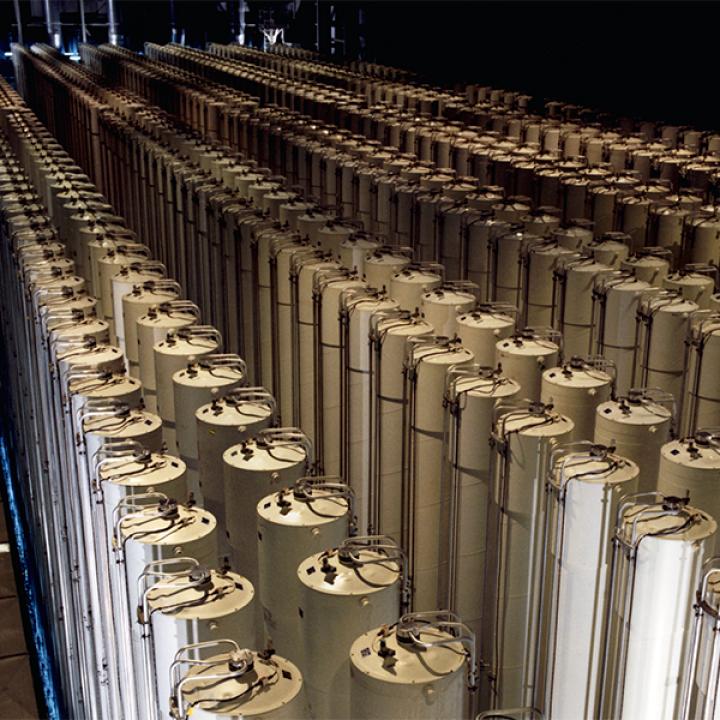

Natural uranium is mostly composed of the non-fissile U-238 isotope, which is not suitable for an atomic bomb. The fissile U-235 isotope is present in much tinier proportions—just seven out of every thousand atoms, a ratio of 7:993 or 0.7%. The initial stages of enriching this material can take months. The first goalpost is typically a ratio of 7:193, producing 3.5% uranium, which is suitable for fueling nuclear power plants. Once enrichment reaches a ratio of 7:5 (60% HEU), only around two more weeks of processing is needed to make weapons-grade 90% HEU (7:1). (For more on the enrichment process, see this Washington Institute infographic or the associated Iran Nuclear Glossary.)

Depending on the sophistication of the design, the “critical mass” needed for a functional nuclear weapon is approximately 15 kg of 90% HEU, about the size of a grapefruit. In February, Iran was found to have reached an enrichment level of more than 80% after an IAEA inspector noticed a modification in its centrifuge piping. The regime’s enrichment levels and production rates slowed down this summer, a shift that diplomats attributed to secret U.S.-Iranian talks that led to the release of several detained American citizens in exchange for more access to frozen oil revenues.

In September, however, Iran ceased granting visas to the IAEA’s most experienced inspectors. And in late November—just weeks after the Iran-backed Hamas terrorist organization attacked Israel and sparked the Gaza war—the agency noticed a change in HEU production levels, spurring it to verify the increased amounts at Natanz and Fordow on December 19 and 24.

Iran’s disturbingly short timeline for producing weapons-grade material does not necessarily mean it is that close to fielding an actual weapon. To make a standard atomic bomb, the regime would need to cast the gaseous 90% HEU output from its centrifuge plants into two metal hemispheres and insert them into a complex assembly of high explosives. The design challenges of making such a device into a warhead capable of withstanding the stresses of ballistic missile launch and reentry are substantial. Yet Iran could circumvent some of those challenges through its ongoing development of sophisticated cruise missiles or drones.

Whatever Tehran’s current nuclear “breakout” timeline may be, the threat of war with Israel is rising. On December 26, Defense Minister Yoav Gallant reiterated that Iran is a major threat, telling a parliamentary committee that Israel is facing a multifront war: “We are being attacked from seven different arenas: Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, [the West Bank], Iraq, Yemen, and Iran. We have already responded...in six of these areas, and I say here in the clearest way: Anyone who acts against us is a potential target, there is no immunity for anyone.” In the context of war in Gaza, ongoing clashes with Hezbollah in Lebanon, and Houthi strikes against shipping in the Red Sea, the news of Iran’s increased nuclear enrichment could further widen the regional crisis.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy at The Washington Institute.