- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

Iranian External Operations in Europe: The Criminal Connection

Also published in International Centre for Counter-Terrorism

Underworld entities like Foxtrot and Rumba give Tehran cover in its increasingly active campaigns against Jewish, Israeli, and other targets across the continent.

In his latest update on national security threats against the United Kingdom, MI5 Director General Ken McCallum revealed that since January 2022, authorities contended with twenty Iranian-backed plots targeting UK citizens and residents. In these plots, he added, “Iranian state actors make extensive use of criminals as proxies—from international drug traffickers to low-level crooks.” In fact, this is a trend seen across Europe.

In September, investigators in Germany and France revealed, Iranian agents—who were acting through European drug traffickers living in Iran—hired European criminals to carry out surveillance of Jews and Jewish businesses in Paris, Munich, and Berlin over the past few months. Once arrested, one French criminal conceded that he was paid one thousand euros to take photographs of a target’s home in Munich in April. According to the French domestic intelligence service DGSI, “The Iranian services have adapted their modus operandi and now more systematically prefer to use people from criminal circles” to carry out their attacks abroad.

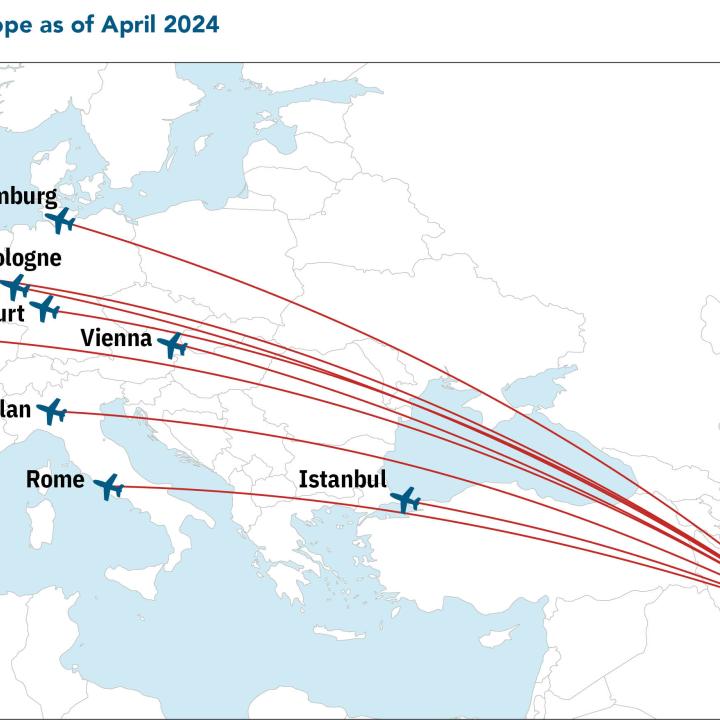

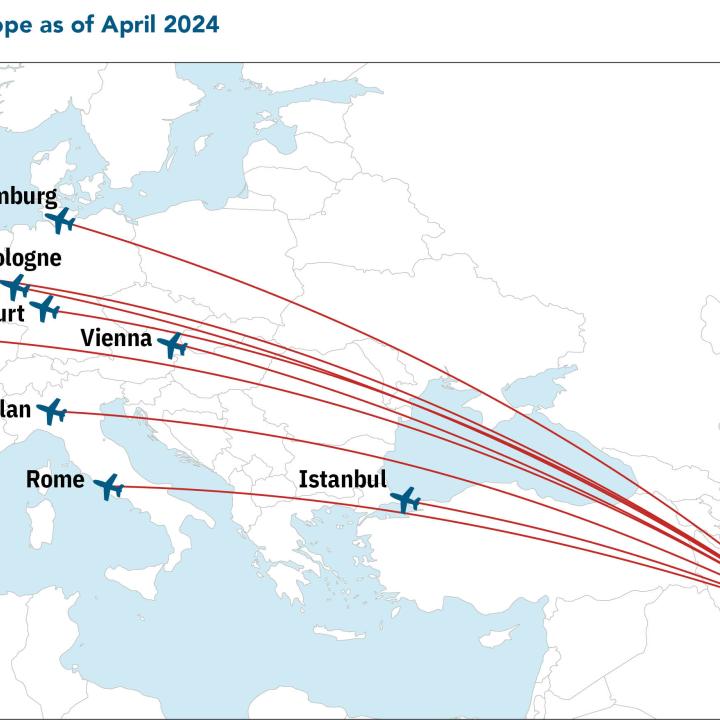

Drawing on a dataset developed by one of the authors (Levitt), trend analysis clearly demonstrates that in the wake of a foiled 2018 Iranian bomb plot outside of Paris, which led to the arrest and conviction of an Iranian diplomat for his role in the plot, Iranian operational leaders, specifically IRGC and MOIS, have increasingly leveraged criminal networks as proxies to carry out attacks abroad to provide distance between Tehran and the operations abroad. The Washington Institute has produced an interactive map drawing on this dataset which depicts Iranian external operations—assassinations, abductions, intimidation and surveillance plots—around the world and shows a marked increase in Iranian operational activity in Europe, with many of these plots involving criminal recruits.

Background: Recent Iranian Operations in Europe Using Criminals

Shortly after the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, the revolutionary leadership embarked on a campaign to assassinate Iranian dissidents and former Iranian officials who served under the Shah’s regime. Over the past forty-five years, Iranian agents have continued to engage in assassination, abduction, intimidation, and surveillance plots targeting regime opponents around the world. Many of these plots occurred in Europe, from the December 1979 assassination of the Shah’s nephew, Shahriar Shafiq, in Paris, to the March 2024 stabbing of Iranian journalist Pouria Zeraati in London.

Drawing on the author’s dataset of Iranian external operations, which are depicted in the Iranian External Operations interactive map and timeline, of the 218 plots in the overall dataset covering 1979 to today, 102 plots occurred in Europe. The pace of Iranian operational activity in Europe has spiked, with over half of these plots (54 cases) occurring between 2021 and 2024. These operations have focused on targeting Iranian dissidents (34 cases), including journalists broadcasting news in Farsi that Tehran would rather not see the light of day, Israeli citizens and diplomats (10 cases), and Jews (7 cases). Furthermore, of these 54 plots, sixteen involved the use of criminal perpetrators to carry out the attacks. Six of these cases targeted Iranian dissidents or journalists, seven targeted Israeli diplomats or embassies, and four targeted Jews or Jewish institutions.

Consider the disrupted plot, nicknamed “the Wedding” by Iranian intelligence, to assassinate two Iran International news anchors in London. Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) hired a people smuggler (referred to in the subsequent investigation as “Ismail” for his own safety) to assassinate Fardad Farahzad (“the groom”) and former presenter Sima Sabet (“the bride”), who were labelled as targets by the IRGC’s Unit 840 in November 2022. Ismail began working with Iranian intelligence in 2016 and was recruited for his role as a transnational criminal based in Europe.

How Criminals Are Used in Europe

Iranian government officials are increasingly using drug traffickers and other criminals in Iran as middlemen to recruit criminals to carry out attacks abroad. Consider the case of Umit B., a drug trafficker from the Lyon region in France with Turkish roots who now reportedly operates out of Iran. “According to Western intelligence,” Der Spiegel reports, “he is allowed to hide in the country from the reach of European investigators, in return for which he helps the regime plan attacks against Jews and Israelis.” This parallels the case of Naji Ibrahim Zindashti, described by the U.S. Treasury Department as an “Iran-based narco-trafficker” whose criminal network “has carried out numerous acts of transnational repression including assassinations and kidnappings across multiple jurisdictions in an attempt to silence the Iranian regime’s perceived critics.” In return, the U.S. Treasury notes, “Iranian security forces protect Zindashti and his criminal empire, enabling Zindashti to thrive in the country’s drug market and live a life of luxury while his network exports the regime’s repression, carrying out heinous operations on the government’s behalf.” The data shows that Iran increasingly leverages criminal networks such as these for its international operations. Not only does Iran use individuals with a criminal past, but organised crime groups as well.

Iran repeatedly leverages a few notable organised criminal gangs, such as Foxtrot, Hell’s Angels, and Rumba, to carry out attacks on Israeli and Jewish targets across Europe. In Sweden, an unexploded grenade was found inside the property of the Israeli Embassy in Stockholm in January 2024. Several months later, Swedish and Israeli intelligence agencies revealed that the attack was orchestrated by the Foxtrot organised crime group at the behest of Iran. According to Swedish intelligence body Säpo, “Iran has been carrying out security-threatening activities in and against Sweden for several years,” using criminal gangs to target Jews, representatives of the Israeli government, and Iranian dissidents. Also in Sweden, Swedish police investigated a shooting outside the Israeli embassy in Stockholm and ultimately detained a fourteen-year-old suspect affiliated with the Rumba criminal organisation, led by gangster Ismail Abdo. In May 2024, a Foxtrot operative, acting on Iranian instructions, threw two airsoft grenades at the Israeli embassy in Brussels, Belgium. In Germany, the IRGC hired a fugitive Hell’s Angels gang boss and dual German-Iranian national, Ramin Yektaparast, to organise terror attacks targeting synagogues in Germany, one in Bochum and the other in Essen in 2021.

In addition to carrying out attacks, foreign governments have warned their citizens of surveillance conducted by criminals on behalf of the Iranian government. In 2023, UK Minister of State for Security Tom Tugendhat stated that Iran is hiring criminal gangs in the United Kingdom to spy on Jews in preparation for a potential assassination campaign targeting prominent members of the Jewish community. Tugendhat notes that Iran is using “non-traditional sources,” including “organised criminal gangs,” and is directing “threats and Iranian operational activity” against potential Jewish targets. These operations have garnered the attention of the international community.

International Response

With 54% of Iranian external operations occurring between 2019 and 2024, Iranian plots continue to receive a growing amount of attention from foreign officials and governments. In response to Iran’s global operations, at least a dozen countries across five continents have warned their citizens about threats from Iran. This includes warnings to specific individuals like Iran International employee Fardad Farahzad. In 2022, the UK Metropolitan Police warned Farahzad of “imminent, credible, and significant” threats to his life and the lives of his family originating from the IRGC.

More broadly, a number of countries have warned their citizens about Iran’s ongoing operations on their soil and have expelled Iranian diplomats as a result. In 2013, according to the Kenyan newspaper Daily Nation, Israel’s embassy in Nairobi alerted the Kenyan Foreign Ministry that Iran and Hezbollah were “collecting operational intelligence and [expressing] open interests in Israeli and Jewish targets around the world including Kenya.” In 2020, Albania expelled its Iranian diplomats and ambassador for “damaging national security” and “breaching diplomatic status.” In 2022, the Royal Thai Police issued an order to be on alert for Iranian spies believed to be in the region gathering intelligence on the movements of Iranian dissidents. In 2022, Ken McCallum, director of MI5, announced that at least ten times between 1 January and 16 November, 2022 Iran’s intelligence services plotted to kidnap and assassinate people in the UK, including British citizens, whom Tehran considers “enemies of the regime.” McCallum added that through its “aggressive intelligence services,” Iran is projecting a “threat to the UK directly.” The Canadian Security Intelligence Service noted in its 2023 annual public report that “Iran will continue to target its perceived enemies even when [they are] living in foreign countries” and that “Iranian threat-related activities directed at Canada and its allies are likely to continue in 2024.” Most recently, U.S. authorities arrested a Pakistani national on charges of plotting to recruit criminals to assassinate prominent U.S. officials within the United States. “This murder-for-hire plot,” FBI Director Christopher Wray stated, “is straight out of the Iranian playbook.”

Conclusion

Iranian external operations are a tactic Tehran employs to address several different perceived threats to the revolutionary regime. Iran targets current and former U.S. officials to avenge the January 2020 targeted killing of Quds Force General Qassem Soleimani. It targets Israeli officials and businesspeople as part of its shadow war with Israel and commitment to Israel’s destruction. It targets Jews—from prominent Jewish businesspersons in Europe to Jewish college students in the U.S.—and it targets Iranian dissidents and journalists abroad who expose the regime’s brutality to the world and empower Iranians to challenge the revolutionary regime.

All these drivers of Iranian external operations are likely to persist, while additional drivers continue to emerge, such as Iran’s pledge to avenge the targeted killing of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran. Increasingly, Iran seeks ways of carrying out operations with some measure of reasonable deniability to reduce the likelihood of a direct response targeting Iran. In April 2024, Iran fired some three hundred rockets and drones at Israel, and Israel targeted Iran in response. Iran seeks to avoid that direct confrontation happening again for fear that such strikes in Iran make the regime look vulnerable, not only to enemies abroad but to opponents at home. As a result, Iran now demonstrates a clear preference for plots that employ intermediaries—typically criminals but also dual-nationals with ties to Shia militant groups affiliated with Iran’s proxy network.

What that means looking forward is that authorities around the world—including Europe—need to develop systems to detect and disrupt such plots. For starters, the European Union, or individual member states, should heed Sweden’s call and classify the IRGC as a terrorist organisation. Ultimately, Sweden’s prime minister recently argued, “The only reasonable option...is that we obtain a common classification of terrorists, so that we can act more broadly than with the sanctions that already exist.” Acts of state-sponsored terrorism, carried out by criminal proxies, cannot be effectively addressed as a criminal matter alone. A common designation would bring to bear a broader range of intelligence and counterterrorism tools to address the threat.

This article was originally published on the ICCT website.