- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3429

Iran’s Flexible Fatwa: How “Expediency” Shapes Nuclear Decisionmaking

The main lesson of the nuclear fatwa is that Tehran’s national security decisions are guided by interests, not ideology, and that progress in negotiations is possible if framed in terms of "regime expediency."

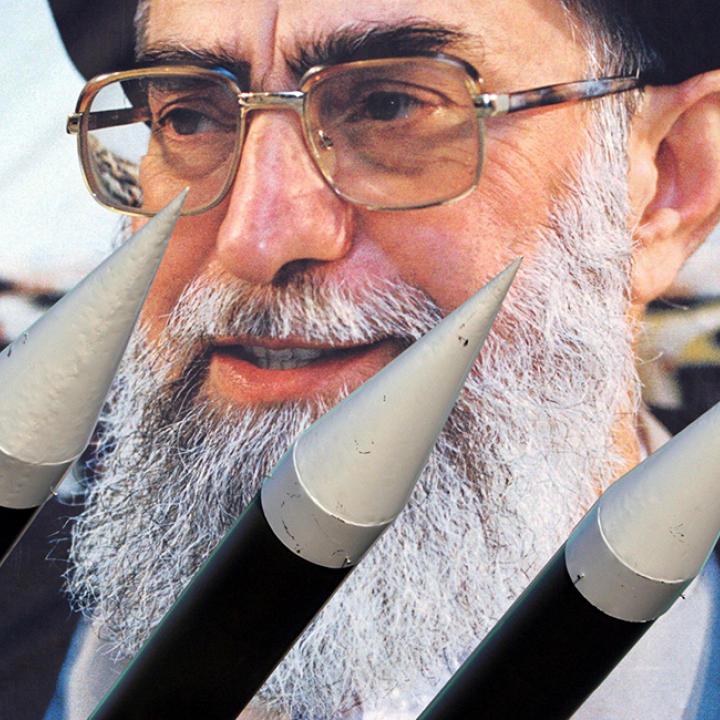

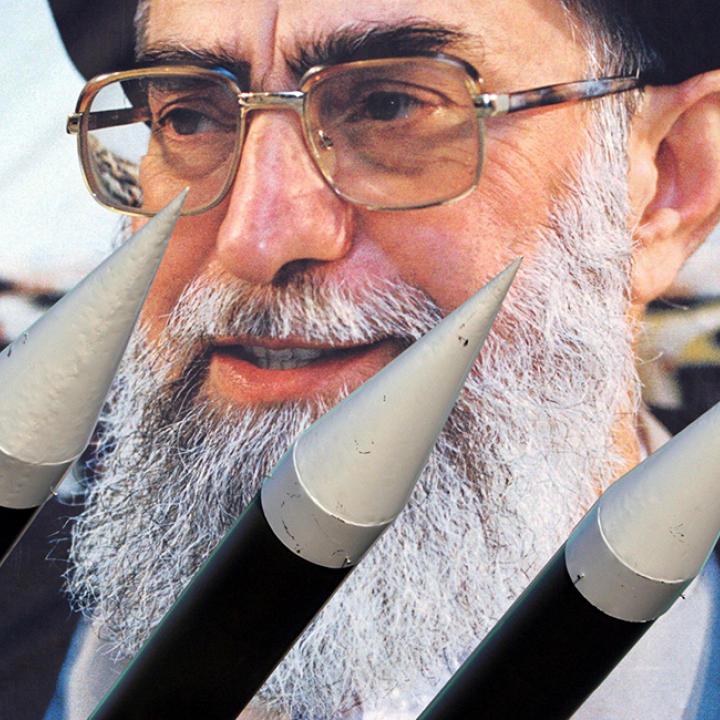

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s years-old fatwa banning nuclear weapons is again making headlines. The regime and its supporters, including former nuclear spokesman Hossein Mousavian, have long claimed that the fatwa is permanent and adduced it as proof that Iran is religiously forbidden from acquiring such weapons. Yet in a January 30 interview with al-Mayadeen television, former Iranian diplomat Amir Mousavi stated, “A fatwa is not permanent, according to Jaafari Shia jurisprudence. A fatwa is issued in accordance with developing circumstances. Therefore, I believe that if the Americans and Zionists act in a dangerous manner, the fatwa might be changed.” His statement confirms that Tehran’s national security decisionmaking is dictated not by religious precepts, but by the principle of “regime expediency” (maslahat-e nezam), whose paramount concern is the survival of the post-revolutionary power structure.

Mousavi is not just any former diplomat; he is also a brigadier-general in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. As Iran’s cultural attache in the Algerian embassy between 2015 and 2018, he was declared persona non grata for spreading Shia sectarian propaganda. He now directs the Center for Strategic Studies and International Relations, an IRGC think tank based in Tehran.

What Spurred the Fatwa, and Why Is It Mutable?

The Supreme Leader first issued an oral nuclear fatwa in 2003, and he has repeated it in numerous speeches since then. These pronouncements, which use a religious idiom to describe nuclear weapons as “forbidden” (haram), have the same legal standing as written fatwas.

The precise formulations used in these pronouncements have varied. Khamenei has at times categorically forbidden the development, stockpiling, and use of nuclear weapons. On other occasions, he appeared to tacitly permit their development and stockpiling, but not use. When addressing a group of top scientists on October 9, 2019, he stated, “Although we could have taken this path [of producing a nuclear weapon], we decided not to...based on Islam’s verdict; it is wrong to make it and it is wrong to stockpile it because it is forbidden to use it.”

Notably, both the initial fatwa and early Iranian efforts to highlight it followed not long after the discovery and public disclosure of the regime’s clandestine nuclear enrichment program in 2002. These efforts should therefore be seen, at least in part, as damage control. The fatwa has been used for other purposes as well:

- To legitimize the nuclear program as a strictly peaceful activity via religious justification

- To deflect potential domestic criticism for the program’s slow progress, its numerous setbacks, and the regime’s decision to eschew a rapid breakout

- To help the regime promote revolutionary Islam as a coequal system of international legitimacy alongside international law, as expressed through proposals in 2013 to get the fatwa enshrined in a UN resolution.

Moreover, fatwas are not immutable—they can be altered depending on circumstances. The founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, modified his position and issued contradictory fatwas on a number of issues, including taxes, military conscription, women’s suffrage, and the legitimacy of the shah’s monarchy. Likewise, Supreme Leader Khamenei could reverse his nuclear fatwa should he deem it necessary. Acknowledging this fact, some former Iranian officials have suggested that parliament pass legislation making the nuclear fatwa law in order to preserve its value as a confidence-building measure with the West.

The reason Iranian fatwas can be reversed is because the principle of “regime expediency” guides policy formulation in the Islamic Republic. Before he died, Khomeini ruled that the regime could destroy a mosque or suspend the observance of Islamic tenets if its interests so dictated, and the Islamic Republic’s constitution invests the Supreme Leader with absolute authority to determine those interests. He can therefore cancel laws or override decisions by various deliberative bodies, including parliament, the Guardian Council, and the Expediency Council.

Regime spokesmen also have a habit of proffering convenient interpretations when it comes to fatwas and foreign policy. For example, when Khomeini’s 1989 fatwa calling for the death of author Salman Rushdie sparked a crisis in relations with Europe, Iranian Foreign Ministry officials tried to downplay its importance, claiming that the fatwa reflected the Supreme Leader’s personal opinion and was not officially binding. Regarding Khamenei’s nuclear fatwa, however, Foreign Ministry officials have repeatedly tried to convince the international community that it is a binding religious ruling and would prevent the country from getting the bomb—at least until Mousavi’s statement last month claiming it would not.

The history of Iran’s fatwa on chemical weapons (CW) raises additional questions. During the Iran-Iraq War, Khomeini reportedly issued a fatwa regarding CW, but it is unclear whether he banned their development and production or only their use. It is also unclear whether the edict was eventually altered in the face of escalating Iraqi chemical warfare. Whatever the matter, the fatwa did not stop Iran from producing small numbers of CW-filled mortar and artillery rounds and aerial bombs, transferring some of these munitions to Libya in 1987, and using some of them against Iraqi troops toward the end of the war. And although Iran joined the Chemical Weapons Convention after the war—reportedly destroying its CW capability in the process—the U.S. government continues to believe that the regime is pursuing pharmaceutical-based agents (possibly fentanyl) for offensive purposes. Thus, if Iran’s chemical fatwa did not preclude it from subsequently acquiring and using CW, it is reasonable to doubt that the nuclear fatwa would preclude it from acquiring and using nuclear weapons if doing so were in the regime’s interests.

Implications for Negotiations

Mousavi’s candid admission on al-Mayadeen should come as no surprise given the abundant information available about Iran’s nuclear weapons R&D efforts, as documented in various International Atomic Energy Agency reports and in the secret Iranian nuclear archive that Israeli intelligence covertly removed from the country in 2018. Yet the greatest significance of his remarks—coming just as the potential for negotiations with a new U.S. administration is ripening—may lie in underscoring how interests rather than ideology will drive Iran’s decisionmaking regarding its nuclear program, missiles, and regional activities.

Previously, this principle of regime expediency led Iran to defer its nuclear ambitions and temporarily suspend the program on at least two occasions: 2003 and 2015. The former decision followed the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, while the latter came despite Tehran’s prior claims that it would never negotiate while under sanctions. The challenge, then, is finding the right combination of pressures and incentives to convince Iran that it is in the regime’s interests to lengthen, strengthen, and broaden the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) while avoiding a nuclear breakout.

This flexibility means that Tehran’s negotiating positions and redlines are not sacrosanct if violating them would advance the regime’s interests. Indeed, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif has already backed off from insisting that the United States take the first step in rejoining the JCPOA, instead talking about ways to “synchronize” or “choreograph” the U.S. reentry.

This also means that the role of trust and confidence in reaching a deal is greatly exaggerated, even though Iranian diplomats incessantly emphasize their importance. Diplomacy can succeed only when Tehran concludes—following an unsentimental, cold-eyed assessment—that a new agreement or series of agreements will advance its interests. At the same time, this likely means that Tehran will adhere to a new agreement only for as long as doing so aligns with its interests. The international community therefore needs to create a framework that can not only facilitate a new deal, but also sustain it for many years to come.

Michael Eisenstadt is the Kahn Fellow and director of the Military and Security Studies Program at The Washington Institute. Mehdi Khalaji, the Institute’s Libitzky Family Fellow, is a former Iranian journalist and Qom-trained theologian.