- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3956

With Its Conventional Deterrence Diminished, Will Iran Go for the Bomb?

Although recent military setbacks have fueled Iranian talk about a possible nuclear breakout, uncertainty about the risks, costs, and utility of weaponization may give the United States leverage to ensure that Tehran continues to hedge.

With Donald Trump’s election victory, Iran faces a period of maximum danger as it confronts the likely return of U.S. “maximum pressure.” This period comes soon after a series of Israeli actions weakened Iran’s deterrent posture, including an October 26 strike that neutralized its strategic air defenses and ability to produce solid-fuel ballistic missiles, leaving it vulnerable to future attacks and unable to replenish partially spent missile stocks. In response, some Iranian officials have urged the regime to bolster deterrence by producing nuclear weapons, stoking concerns that it might soon abandon its nuclear hedging strategy.

Creeping Toward Breakout

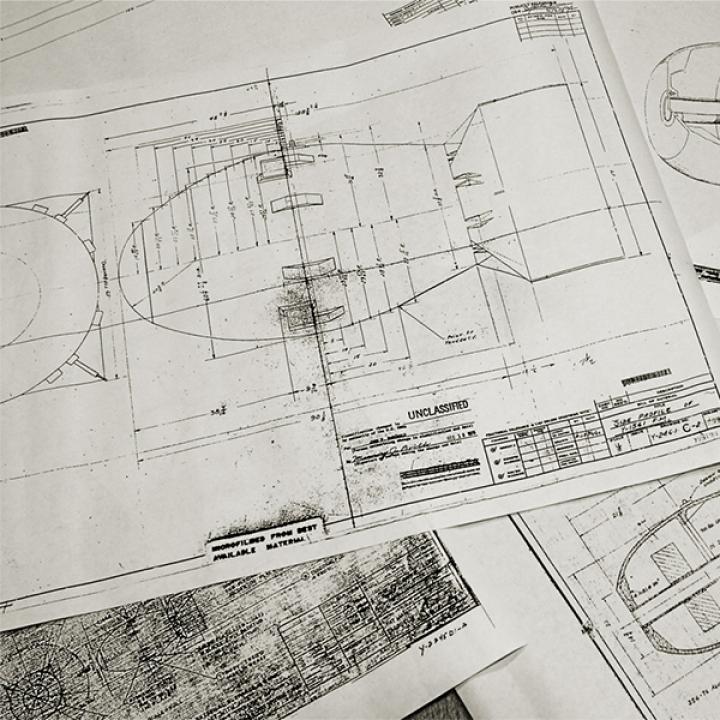

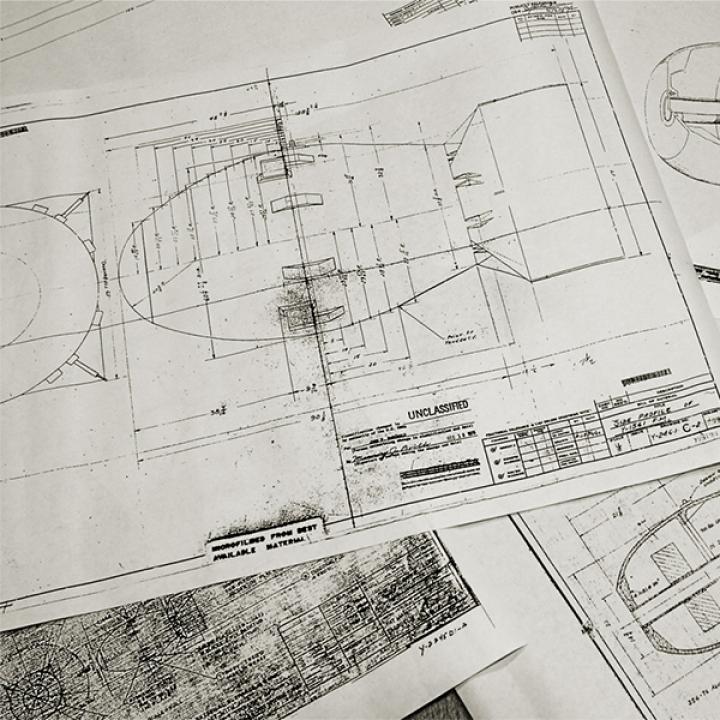

This spring and summer, several Iranian officials warned that a worsening threat environment could cause the regime to rethink its nuclear doctrine. Meanwhile, the International Atomic Energy Agency reported that Tehran had begun installing advanced centrifuges in uranium enrichment facilities at Fordow and Natanz, while Israeli and American officials told journalists that it had engaged in metallurgical, computer modeling, and explosives research potentially related to nuclear weapons work. And a U.S. intelligence assessment released in July asserted that Iran had “undertaken activities that better position it to produce a nuclear device, if it chooses to do so.” Unsurprisingly, then, Israel’s October 26 strike also hit a facility near Tehran reportedly engaged in these weaponization activities.

At the same time, the regime adopted a more risk-acceptant approach toward Israel, believing that the Jewish state was increasingly vulnerable due to the Gaza war, associated U.S.-Israel tensions, and Iran’s massive missile force. The regime was also convinced that it needed to respond firmly to various Israeli actions, including targeted strikes on senior Iranian and proxy figures in Damascus, Tehran, and Beirut. Accordingly, Iran launched major missile strikes against Israel on April 13 and October 1. These actions may herald a more risk-acceptant approach toward the development of nuclear weapons as well, unless the United States and its partners adopt a more assertive approach in the coming months.

Iran’s Proliferation Calculus

Tehran halted most of its clandestine nuclear weapons work in 2003, after the program was exposed by an opposition group. It subsequently adopted a hedging strategy to preserve a nuclear option because the risks and costs of going for the bomb—diplomatic isolation, economic sanctions, military strikes, and perhaps a regional nuclear proliferation cascade—were deemed unacceptable. Tehran’s proliferation calculus has always considered a broad range of factors, and hedging offered many of the benefits of getting the bomb without the attendant risks and costs.

Since then, some of the concerns that led Iran to hedge have abated, while others remain acute. For example, it is more difficult to isolate Tehran today than in the past. The regime has strengthened its ties with Russia and China, while various U.S. partners have hedged their bets by reaching out to Tehran. Yet Iran remains vulnerable to sanctions—President Masoud Pezeshkian has indicated that sanctions relief remains a priority, while Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei would likely support such efforts if Iran does not have to pay too high a price.

Moreover, the threat of military action is higher than ever before. Israeli aircraft overflew Iran with impunity on October 26, knowing exactly where to strike to maximize damage to the regime’s ballistic missile production capabilities during an operation conducted in full coordination with the United States. Indeed, Israeli intelligence has repeatedly penetrated Iran’s most sensitive activities. Tehran could reasonably conclude that if it attempted a nuclear breakout now, Israel would probably know about it, and the lame-duck Biden administration might support, if not participate in, a strike to thwart it. This applies a fortiori to the incoming Trump administration.

In addition, Iran may need weeks or months to manufacture a viable nuclear weapon, potentially giving its enemies time to act. The recent use of B-2 bombers to hit buried Houthi drone and missile storage facilities in Yemen indicates that the United States might use this asset against Iran if a strike against its nuclear program is deemed necessary. The B-2 is the only aircraft cleared to drop the 30,000-pound GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator, the only conventional munition capable of reaching Iran’s underground enrichment facility at Fordow.

The Limits of (Nuclear) Power

Tehran also has to consider whether the benefits of the bomb would be worth the risks of an attempted breakout. Khamenei has spoken about this on several occasions, whether to justify the post-2003 hedging policy or as part of a genuine evolution in his thinking. For example, he has stated that the Afghan mujahedin defeated the Soviet Union and Iran thwarted the United States in Iraq and Syria, even though both superpowers possessed nuclear weapons. He also pointed out that nuclear weapons did not prevent the collapse of the Soviet Union. In contrast, there is no evidence that he sees nuclear weapons as key to the Islamic Republic’s survival; if he did, he almost certainly would not have agreed to pause or dismantle the nuclear program on several occasions to avoid diplomatic isolation or obtain sanctions relief.

Furthermore, Iran has been unable to protect its most prominent nuclear scientists from Israeli hit squads, its most important nuclear facilities from Israeli saboteurs, or its nuclear archives from theft by Israeli agents. Until the regime solves this problem—and recent events provide no confidence on that score—it might not want to produce nuclear weapons that could be vulnerable to sabotage or diversion by foreign agents or domestic terrorists.

At the moment, however, the most important reason for Tehran to avoid a breakout may be its conventional military vulnerability. It thus faces a conundrum: although nuclear weapons could help redress this shortcoming, the worst time to go for the bomb is when its ability to deter or respond to a strike against the program is diminished.

“Keep the Hedger Hedging”

With the tentative adoption of a more risk-acceptant approach toward Israel, Iran may have reached a tipping point. Washington must therefore do everything it can to prevent this approach from becoming the new normal and induce Tehran to keep hedging. Although a hedging Iran is an undesirable outcome, it is preferable to a nuclear-armed Iran. It is also preferable to a major preventive strike on Iran’s nuclear sites, which would likely buy just a year or two of respite before the program is reconstituted and has to be struck again. Just as “mowing the grass” ultimately failed in Gaza, it would likely fail in Iran. And a preventive strike could convince Tehran that building a bomb is imperative.

Facing a second Trump term, Iran might further ramp up production of advanced centrifuges and fissile material to create additional leverage over Washington, or to enable a more rapid breakout if tensions escalate further. It might even view the period before Inauguration Day as a window of opportunity to take the first steps toward a breakout so that it can deal with the new administration from a position of strength. Such moves could include hiding fissile material at unsafeguarded sites or clandestine enrichment facilities.

To address these risks, U.S. leaders have several options. First, the incoming administration should, like its predecessors, publicly state that it will not allow Iran to acquire nuclear weapons. Second, with help from Israel and other partners, the United States should take the following steps to deter Tehran from getting the bomb and keep it hedging for as long as possible:

- Continue close cooperation with Israel and other allies to signal Iran that it is facing a broad coalition.

- Seek agreement from a broad array of U.S. allies that they will participate in a maximum pressure campaign against Iran if it enriches uranium beyond current levels (60 percent) or otherwise attempts a nuclear breakout.

- Step up the use of B-2 stealth bombers in regional exercises and operations to signal that Washington might use this platform if Iran attempts a breakout.

- Deploy the U.S. Army’s new Dark Eagle long-range hypersonic glide vehicle to the region to suggest that Iran’s leadership could be targeted if they order a breakout, since not all nuclear targets may be reachable.

- Demonstrate a persistent ability to penetrate Tehran’s nuclear program by cyber and other means to show that any nuclear weapons would be vulnerable to sabotage and diversion, and could therefore pose a risk to the regime.

- Launch an influence campaign in Farsi-language social media questioning the utility of nuclear weapons and underscoring the dangers they could pose to Iran in the event of sabotage, diversion, or a resultant regional proliferation cascade.

Given Tehran’s longstanding concerns about the potential risks and costs of going for the bomb, even relatively small policy adjustments that play on Khamenei’s traditional risk aversion and paranoia may dissuade the regime from attempting a breakout. Such fears have undoubtedly been reinforced by Israel’s recent elimination of Hezbollah’s senior leadership.

Finally, to prevent Tehran’s more risk-acceptant approach from becoming the new normal, Washington should encourage Israel to answer any future attacks with calibrated counterstrikes that further degrade Iran’s conventional military capabilities, while the threat of action against nuclear and regime leadership targets deters a breakout. In this way, the United States and its allies can quell the conventional threat, avert a nuclear breakout, and perhaps pave the way for a comprehensive deal with Iran after the Trump administration takes office in January.

Michael Eisenstadt is the Kahn Fellow and director of the Military and Security Studies Program at The Washington Institute. This PolicyWatch draws from his forthcoming study If Iran Gets the Bomb: Weapons, Force Posture, Strategy, as well as his previous study Iran’s Nuclear Hedging Strategy: Shaping the Islamic Republic’s Proliferation Calculus.