- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3259

Latest Battle for Idlib Could Send Another Wave of Refugees to Europe

Various displacement scenarios may unfold as the fighting escalates, each carrying a high risk of negative humanitarian and economic consequences even if the parties live up to their promises.

The battle for Idlib province, the last stronghold of Syrian rebel forces, is heating up again. As Turkish troops clash with Assad regime forces and displaced civilians continue piling up along the border, various foreign and domestic players are considering moves that could send hundreds of thousands of refugees to other parts of Syria, northern Iraq, or Europe.

EUROPE’S FEARS, TURKEY’S LEVERAGE

The EU countries are very afraid of seeing a new wave of Syrian refugees sweep over the continent. Two of the countries that opened their doors so generously during the previous mass wave of 2015—Germany and Sweden—are now unwilling to do so again. France was not greatly affected by the previous wave, but President Emmanuel Macron is nevertheless trying to avoid becoming the next mass haven. Instead, he has proposed a mechanism that would distribute new refugees proportionally between all EU member states. Eastern European countries have flatly rejected this idea, however, especially Poland and Hungary.

One of the reasons why Europe is so hesitant to reopen its doors is because it has suffered multiple terrorist attacks in recent years, some of them perpetrated by jihadists who infiltrated the continent under mechanisms intended to help refugees. Last month’s arrest of Islam Alloush in Marseilles is a telling example of how European intelligence services are often unable to separate the wheat from the chaff when screening for violent radicals. A former official with the brutal Syrian Islamist rebel group Jaish al-Islam, he arrived in Europe last year on a student visa as part of an EU scholarship program, then resided there for months before being picked up on charges of torture and other war crimes.

The potential economic cost of hosting millions of new refugees has troubled Europe as well. Moreover, the continent is currently coping with a populist, xenophobic electoral wave. Combined with potential domino effects stemming from the battle for Idlib, these factors pose serious threats to EU cohesion on all issues and endanger the costly status quo Europe established with Turkey in 2015.

Turkey is well aware of the EU’s dilemma. Because Syrian refugees are not economic migrants, but rather a case of war migration by people in real distress, many European leaders have felt obligated to exhibit some degree of solidarity with them. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has taken advantage of this sentiment by essentially blackmailing the EU, which has financed the millions of Syrian refugees still residing in Turkey with a support plan of 6 billion euros since 2016. The EU also continues to subsidize Turkish agriculture, tourism, culture, and other sectors as if the country were still engaged in a serious effort to join the EU, even though both sides know that is no longer the case. Last but not least, European officials have been careful not to condemn or punish Ankara for human rights violations stemming from its military operations against Kurds in Syria, if only because they do not have an alternative plan at ready if Erdogan decides to retaliate by opening the Pandora’s box of mass migration.

DISPLACEMENT AND REFUGEE SCENARIOS

Since December, the Syrian army’s rapid advance in Idlib has prompted nearly 400,000 civilians to take refuge near the province’s northern border with Turkey, where approximately one million internally displaced persons are already gathered. In all, the fighting could wind up displacing around 2.5 million people in Idlib if the regime campaign is carried out to its fruition. Erdogan has built a wall to prevent these IDPs from crossing the border and adding to Turkey’s existing Syrian refugee population of 3.5 million—a number he now deems politically and economically unsustainable after years of generous hosting.

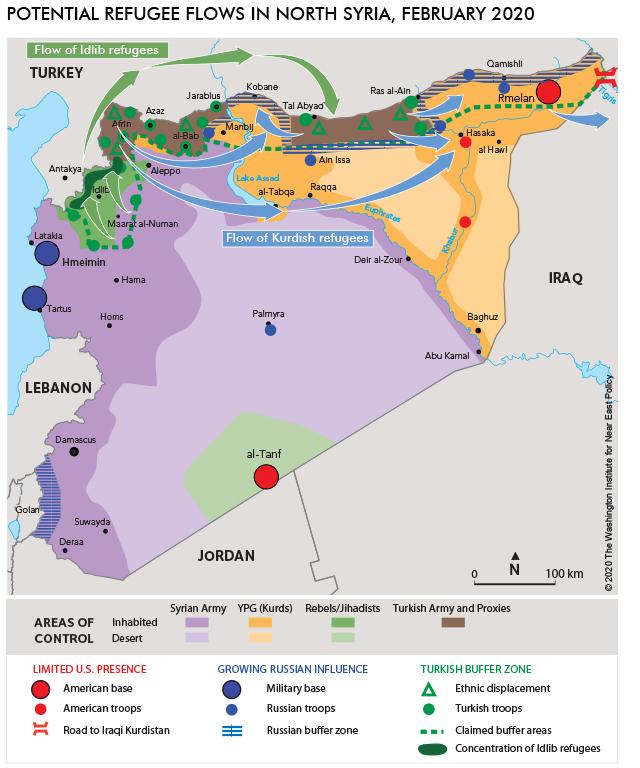

Click on map for larger version.

Although Erdogan has attempted to buy time by forcibly slowing the Syrian advance and delivering military ultimatums to Damascus, he will ultimately need to choose one of two solutions: let the IDPs cross Turkish territory toward their eventual goal of reaching Europe, or send them to other parts of Syria. If he takes the first approach, the EU would immediately cut off its massive financial aid to Turkey. Yet the second approach presents obstacles of its own. Most Syrian refugees do not want to return to a devastated country where many of them would be at risk of reprisal given their involvement in the rebellion. Even settling in areas of Syria controlled by Turkey would require massive economic development and heavy local security, neither of which is currently present. In contrast, the millions of refugees already in Turkey are content to enjoy much better living conditions and the persistent, if dim, hope of eventual EU accession.

Despite these hurdles, Erdogan believes that the threat of a new refugee wave is great enough to spur Europe into accepting and financing option two. The current version of Turkey’s plan is to establish a thirty-two-kilometer-deep buffer zone from the Tigris River in northeast Syria all the way to Idlib, and then move as many Syrian refugees as possible there. Yet that would require resuming stalled military operations against the Syrian Kurds, with the goal of taking the various border towns not already seized by Turkey and its proxy militias (all except for Qamishli, which would remain under the Assad regime’s sovereignty).

The ethnic repercussions of such a campaign would no doubt be serious. Since January 2018, the date of Turkey’s offensive against Afrin in northwest Syria, more than half of that canton’s Kurdish population (200,000 inhabitants) have left. Further east, all of the Kurds (70,000) between Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain have fled due to subsequent Turkish incursions. Erdogan’s objective is to replace these Kurds with Sunni Arabs in order to establish a non-Kurdish buffer area along the entire border—an outcome that would align with his broader effort to suppress the violent Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) at home and its sister militia in north Syria, the People’s Defense Units (YPG).

This process is well underway in Afrin, with the families of Syrian fighters from the Turkish-backed “Syrian National Army” militia occupying the homes of Kurds who have fled. Some displaced Syrians have also been moved to Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain, though that effort has been slowed by the zone’s persistent insecurity and lack of territorial continuity with Idlib, the area most urgently in need of IDP resettlement. Most of the refugees in Idlib face deplorable humanitarian conditions and the fear of falling under the yoke of the Syrian army, which is moving inexorably closer.

If Erdogan succeeds in creating his entire buffer zone, 650,000 inhabitants of northeast Syria—three-quarters of whom are Kurds—would likely be displaced. Rather than move to other parts of Syria, most would presumably flee to the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq and then on to Europe, where they have readymade migration networks.

Currently, Russia and the United States oppose Turkey’s plan, partly because it would entail another offensive against the Kurds, and also because of the financial costs required by the proposed resettlement. Even if these two major obstacles are removed, the fact remains that the proposed buffer areas would not be able to absorb the roughly 2.5 million Syrians trapped in Idlib—at most, only a few hundred thousand could be supported. As such, the majority of Idlib’s civilians would remain stranded at the foot of Turkey’s border wall, threatened by a potentially revenge-minded Syrian army and subject to jihadist groups that would likely seek to profit from running the small remaining sanctuary.

The EU would then face a potential double wave of refugees. The first would be diffuse, composed of Kurds gradually transiting Iraqi Kurdistan en route to Europe. The second would likely be more sudden and brutal—Turkey cannot contain the pressure of 2.5 million people forever, so violent breaches of its Idlib wall would be inevitable.

Russia has sought to convince the Europeans that there is a third option: namely, Damascus issuing a broad amnesty and offering security guarantees to the province’s entire population, with these concessions facilitated by generous EU financial assistance and the lifting of sanctions against Damascus. Yet this idea has not gained any traction in Europe, in part because of the Assad regime’s known track record of breaking such guarantees and continuing its brutal treatment of displaced Syrians.

Until these questions are resolved, the threat of a new refugee march toward the EU will keep rising, leading some states to consider ways to fortify their frontiers—Greece, for example, has proposed the construction of floating walls in the Aegean Sea to block migrant boats. In this sense, the course of events in Idlib may play a decisive role in Europe’s most pressing dilemma: how to maintain its humanitarian principles while still preserving its security and unity.

Fabrice Balanche is an associate professor at the University of Lyon 2, an adjunct fellow with The Washington Institute, and author of Sectarianism in Syria’s Civil War: A Geopolitical Study.