- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3982

Lebanon’s New Prime Minister Approaches the Next Crossroads on Hezbollah

Salam has promised to enforce accountability and implement the ceasefire with Israel; independent Shia cabinet ministers can help him reach those goals while showing there is an alternative to Hezbollah.

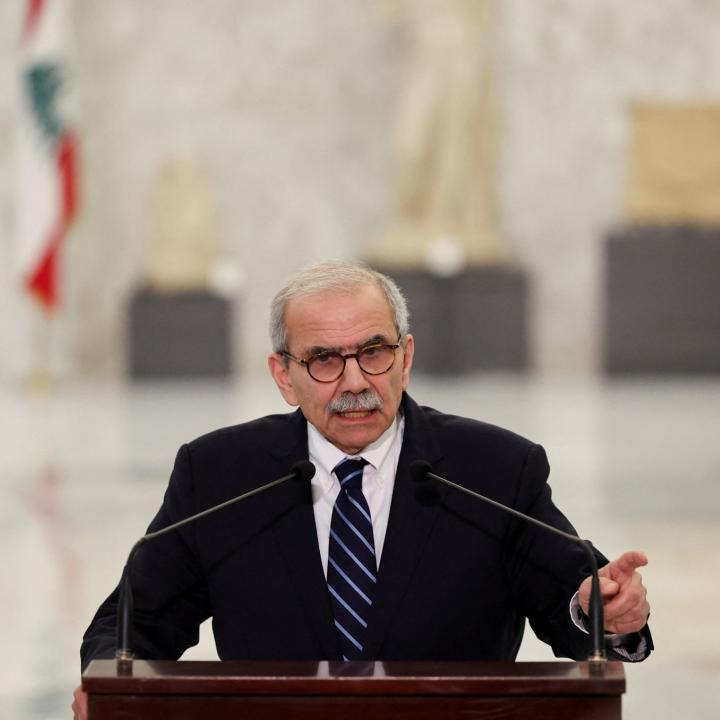

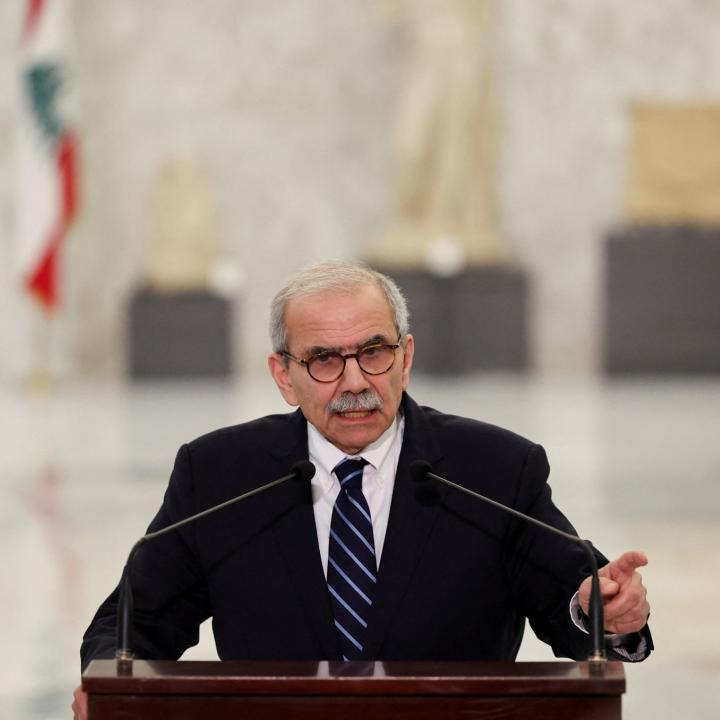

In his first speech as prime minister, Nawaf Salam stated that he would “immediately start coordinating” with new president Joseph Aoun to “rebuild the project for the new Lebanon,” adding that he wants to work with all Lebanese people and factions. As expected from an International Court of Justice official with a history of condemning Israel, Salam was also very critical of Israel’s occupation “of Lebanese land.” Yet his main focus was laying out his plans and promises to the Lebanese people. In addition to reforms and reconstruction, he emphasized four top objectives: fully implementing the Taif Accord, signed in 1990 to end after the country’s civil war; implementing every term of the ceasefire agreement signed with Israel last November; ensuring that “state authority is established across all Lebanese territory”; and seeking justice for the victims of the 2020 Beirut port explosion.

Time Will Reveal Salam’s Priorities

All of these goals emphasize Lebanon’s sovereignty, its aspirations to respect international commitments, and its promises to contain Hezbollah through legal means. Salam’s promises will be tested as he turns toward forming a government and appointing ministers to key portfolios, particularly foreign affairs, finance, defense, and justice.

His emphasis on the port blast is most significant internally. For years, Hezbollah and its political allies worked hard to stop Judge Tarek Bitar from concluding his investigation of that disaster. Just two days after Salam was appointed, however, Bitar charged ten new suspects in the case. If this process goes swiftly, Hezbollah officials and their allies may soon be indicted—an unprecedented action by the Lebanese judicial system.

Meanwhile, Hezbollah and the Amal movement boycotted the nonbinding parliamentary consultations that Salam held on January 15 to inform his choice of cabinet members. They apparently did so to express their resentment against Aoun for refusing their request to postpone their consultation by one day. During his inaugural speech the previous day, the prime minister had promised to push for accountability, starting with the Beirut blast investigation.

Hezbollah’s bid to pressure Salam and Aoun via boycott should be met with resolve. To be sure, the Sunni prime minister and Maronite Christian president want inclusion—Salam does not want to form the government without Shia representation. But Hezbollah and Amal are clearly not the right Shia representatives after the destruction they have brought upon the towns and cities they represent, particularly since October 2023. Salam and Aoun are signaling Shia communities that they have the opportunity to become part of the new Lebanon and join their fellow countrymen in rebuilding the state. The best way to bring them into the fold is by appointing well-qualified independent Shia figures as ministers in the new government rather than Hezbollah-aligned figures, thereby demonstrating that the militia is not the only political option for the Shia.

If Salam has the nerve to isolate Hezbollah and simultaneously include the Shia, he will be headed in the right direction. And if Judge Bitar is empowered to issue the necessary indictments for past crimes, Hezbollah will have to think hard before it threatens or assassinates its domestic opponents again.

Moreover, Salam will come to another crossroads once his government prepares to issue its first ministerial statement. Past statements have traditionally included the phrase “the people, the army, and the resistance” as the basis for Lebanon’s security, essentially legitimizing Hezbollah’s arsenal and military role. Will Salam remove that motto? If he is willing to confront Hezbollah and its allies in parliament by refusing to legalize Hezbollah’s weapons through such wording, he may be able to project enough power to reach the next series of tests: namely, making senior security and financial appointments and providing the Lebanese Armed Forces with the political backing they need to implement UN resolutions.

Only time will tell, but Salam’s early remarks as prime minister and his past record of eschewing corruption are promising. The next few months will confirm his priorities and indicate his willingness to truly confront Hezbollah and its cronies.

Hezbollah’s Failures Are Salam’s Opportunities

The dramatic political developments in Lebanon—and next door in Syria—reflect Hezbollah’s growing weakness. The group failed to sabotage Aoun’s selection as president and was left with no choice but to vote for him in the second round of parliamentary balloting. To save face, the group’s outlets claimed that during the two hours of negotiations between rounds of voting, the “Shia duo” of Hezbollah and Amal forced Aoun to promise that the new government would allow the militia “to keep its arms north of the Litani River” and have a major say in forming the new government, “especially the Finance Ministry.” Within forty-eight hours, however, Hezbollah outlets were backing down from these claims.

Meanwhile, Hezbollah nominated Najib Mikati to return as prime minister, but an overwhelming majority of parliament ignored the group’s lobbying on his behalf and instead chose Salam, who was never considered friendly toward the “resistance.” The lopsided final tally in favor of Salam (84 votes to 9) stemmed from a mass defection of most factions previously allied with Hezbollah, including Free Patriotic Movement leader Gebran Bassil.

Even if Hezbollah finds a way to become part of the new government, it will probably lose more of its traditional power over decisionmaking if Salam and Aoun stick to their promises. In that scenario, the group would be forced to adjust to a new reality in which its staunch critics formerly in the opposition are now given key portfolios.

Hezbollah is particularly concerned about what these developments may bode for Lebanon’s next election in May 2026. The group previously lost its parliamentary majority in the 2022 election but managed to continue obstructing its opponents through various political machinations and threats. Much has changed since then, however—Hezbollah now stands to lose more allies in parliament, and the disillusioned Shia community will probably be on the lookout for alternatives. For example, the group’s main political partner, Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri, is eighty-six years old and may not be in the running to return to his position next year.

One of the biggest potential factors in swaying Shia away from Hezbollah will be the crucial upcoming decisions on who funds Lebanon’s reconstruction and the mechanisms by which the process is conducted and monitored. On January 23, Saudi foreign minister Faisal bin Farhan will visit Beirut to “launch a new phase” in the bilateral relationship. If the Saudis are going to help with reconstruction, however, they need to make sure Hezbollah is not part of this phase.

Amid these shifts and the prospect of continued Israeli strikes on its military positions, Hezbollah will probably refocus most of its attention on domestic matters in the near term to maintain some of its political influence. So far, however, it has proven incapable of fulfilling any of the promises that its leader, Naim Qassem, has made about reconstruction and political sway, nor has it been able to exert any visible influence over the nascent political process. Accordingly, Salam and Aoun should feel emboldened to continue containing the group, paving the way to deeper change in 2026. If Salam shows determination in implementing his promises, the international community should reward him with ample support; but if he backs off and resorts to the usual Lebanese game of consensus and compromise with Hezbollah, he and his government should be held accountable.

Hanin Ghaddar is the Friedmann Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute and author of Hezbollahland: Mapping Dahiya and Lebanon’s Shia Community. Ehud Yaari is the Institute’s Lafer International Fellow and a Middle East commentator for Israel’s Channel 12 television.