- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3480

Lines in the Sea: The Israel-Lebanon Maritime Border Dispute

Benefitting from offshore natural gas reserves should be a win-win situation, but in this case the players may turn it into a zero-sum game.

On May 4, Israel and Lebanon are set to resume U.S.-mediated talks on resolving their maritime border dispute after months of setbacks on the issue. Previous diplomacy had reduced the contested area to a 330-square-mile triangle of water in the East Mediterranean, but that progress was thrown into the air last October when Beirut enlarged its claim in a way that encroached on two not-yet-exploited Israeli gas fields, Karish and Tanin.

On the surface, the matter is a legal dispute over property rights, but numerous other factors are at play. Diplomatically, the two countries have yet to establish formal relations. Geographically, they have no agreed land border either; the current demarcation is the “Blue Line” drawn by the United Nations in 2000 after Israel withdrew forces positioned in southern Lebanon to stop terrorist attacks. Militarily, Israeli forces are on constant alert against Hezbollah, which has used Syrian and Iranian assistance to amass a huge arsenal of rockets and missiles capable of hitting targets deep inside Israel. Economically, Lebanon cannot produce enough electricity for its population, many of whom rely on private generators. And in energy terms, substantial gas resources have been discovered and exploited in Israeli waters, while Lebanon has so far been unsuccessful in that regard.

This week’s talks will be held at the UN peacekeeping base at Rosh Hanikra/Ras Naqoura, located on the border overlooking the sea. The official agenda has not been revealed, but the underlying parameters are as follows:

Territorial Waters and Exclusive Economic Zones

Countries can claim up to 12 nautical miles from their coasts as territorial waters. (One nautical mile is approximately 1.15 miles.) The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea allows countries to claim a further 200 nautical miles as an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) for fishing and mineral rights. In the event that the waters between two countries are not wide enough to allow for claims of that size, the agreed midpoint becomes the boundary. Oil and gas fields can extend beyond such boundaries; in such cases, internationally established mechanisms are often used to split costs and revenues proportionally.

Maritime Borders Between Adjacent Countries

To draw a maritime border and EEZ, countries that share a coastline must agree on two points: where to begin the line (typically where their land border reaches the sea), and what bearing it will take. In Israel and Lebanon’s case, both points are subject to dispute.

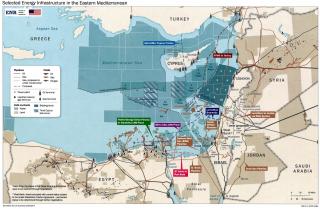

One accepted convention for determining the bearing of a maritime border and EEZ is to draw them perpendicular to the “line of the coast,” but different interpretations of this theoretical line can produce different bearings. For example, if one asserts that Israel and Lebanon’s line of the coast extends from Tyre to Acre, then the resultant border/EEZ would have a bearing of 290 degrees. But if the line of the coast extends from Beirut to Haifa, then the bearing would be 295 degrees—a significant difference when deciding how hydrocarbon reserves far off the coast will be apportioned (see map). Further complicating the calculus, Lebanon has sometimes argued that the maritime border should continue the bearing of the (disputed) land border, which at the coast is 270 degrees, or due west.

Maritime Borders Between Multiple Countries

Because Lebanon, Israel, and Cyprus are comparatively close to each other in the East Mediterranean, none of them can assert a full 200-nautical-mile EEZ, forcing them to calculate a point equidistant between them. But getting all three to agree on the same point is difficult. Cyprus realized this when negotiating an EEZ with Lebanon in 2007, making “Point 1” the southern terminus of that line. Three years later, “Point 23” was designated as the northern terminus of the island’s newly negotiated EEZ boundary with Israel. Between these two points is the aforementioned triangle of disputed waters between Israel and Lebanon (see Blocks 8 and 9 on the map). One U.S. proposal has been to divide this pizza slice in a 56:44 ratio, with Lebanon taking the larger bite.

Islands

Islands can be extraordinarily contentious when countries are attempting to draw maritime borders. For instance, Turkey argues that all islands—even ones as large as Cyprus—should only be granted territorial waters, not EEZs. Besides Ankara’s rancorous tensions with Cyprus, this mindset reflects 200 years of history with Greece, whose claims in the Aegean Sea have prevented Turkey from asserting control in waters between the two countries. Similarly, for the tiny Greek island of Kastellorizo—located a mile off Turkey’s southern coast with a population around 500—Athens has claimed a 200-nautical-mile EEZ stretching as far as Egypt’s EEZ. This assertion helped spur Turkey’s decision to intervene in Libya.

Elsewhere, a dispute has emerged over the islet of Tekhelet, which lies in Israeli waters just south of Rosh Hanikra/Ras Naqoura. A small, rocky outcrop nearly a mile offshore, Tekhelet is the northernmost of five similar islets that form a reef-like feature stretching four miles south to Achziv, the ruins of a Phoenician port dating back more than 2,000 years. Categorized in technical terms as “drying features,” all of the islets are part of a nature reserve where visitors are forbidden. In a previous EEZ proposal, Lebanon conceded the islets to Israel; in turn, Israel pushed its definition of the maritime border northward. At the end of last year, however, Beirut reversed its position and declared that the islets were uninhabited and therefore not relevant to the negotiations. Yet this has not stopped Lebanese officials from asserting a maritime border with Syria in which they use their own uninhabited nature-reserve islets to stake a more favorable claim.

Adjudication

This week’s talks seek movement toward a maritime deal even if Beirut does not want to take the larger step of recognizing Israel’s existence. Arguments over offshore waters are common across the world, and many have been resolved to the mutual advantage of the parties. In the absence of a negotiated agreement, the parties can seek binding arbitration or a judgment by the International Court of Justice in The Hague. Yet this seems unlikely in the case of Lebanon and Israel given the lack of diplomatic recognition. The fact that Lebanon currently has a caretaker government could be a further impediment to resolution.

The Politics

When Lebanon expanded its claim last year, Israel arguably missed a negotiating trick by not quickly and publicly expanding its own claim. That move did not come until last week—according to the Jerusalem Post, Israel is now prepared to argue that the maritime line should be an azimuth bearing 310 degrees from the coast at Rosh Hanikra/Ras Naqoura, a significant northwesterly shift from previous proposals. The report did not mention the legal backing for this position.

Time Constraints

The licenses for exploring the Israeli blocks containing the Karish and Tanin fields are held by the Greek company Energean. Exploitation of Karish could reportedly begin in early 2022 using a floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) vessel currently being constructed in Singapore. Such vessels remove the need for a seabed pipeline to shore but cannot operate in contested waters.

For its part, Lebanon is hoping that the French company Total will carry out exploratory drilling in Block 9, part of which lies in the contested triangle with Israel. The block is deemed likely to contain hydrocarbons, but this is not a certainty, and Total is reluctant to drill so long as ownership is contested. Israel’s claimed 310-degree line would give it sovereignty over roughly one-fifth of Block 9 and almost all of Block 8.

Conclusion

Israel and Lebanon’s sharply differing views on maritime boundaries represent a significant challenge to U.S. diplomacy, which has quietly encouraged development of offshore oil and gas in the East Mediterranean with some success in recent years. An agreement this week or in the near term may be elusive—Israel does not want to concede even partial ownership of its discovered gas fields or delay them coming into production because of perceived Lebanese obstructionism. But a confrontation, perhaps accompanied by threats of force by Hezbollah, could deter other investors from committing to projects off Israel’s coast—which may be part of Beirut’s motivation. The task ahead for American mediators will not be easy.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy at The Washington Institute.