- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3462

One Less Hurdle Before Iraqi Elections

A complicated parliamentary compromise has reactivated some of the machinery required for this year’s proposed ballot and a potential resolution to the KRG energy dispute, though the country’s hobbled legal institutions are still holding back reform.

On March 19, the Iraqi Council of Representatives (COR) amended Law No. 30 of 2005 establishing the Federal Supreme Court (FSC), the country’s highest constitutional court. Although the decision stems from a thorny political compromise and fails to resolve Iraq’s deeper legal pathologies, it will nonetheless help overcome a serious barrier to holding early elections in October. The FSC has been paralyzed since 2019 by a self-inflicted constitutional crisis, but it can now fulfill its mandated duty of ratifying election results. It might also be able to dust off a case regarding national oil and natural gas management rights—a subject of bitter dispute between Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Yet if Iraq keeps kicking the can down the road on constitutionally mandated reforms, the situation could lead to even worse political and legal complications.

A Broken Third Pillar

Since Iraq’s current constitution was adopted in 2005, the judicial branch has undergone a number of haphazard transitions and rapid changes whose net effect has been to blunt the rule of law. Among these negative consequences is a political process periodically marred by constitutional violations.

Article 92 (2) of the constitution mandated the creation of a federal supreme court and tasked the legislature with achieving this end. Yet despite bearing that name, the current FSC was not established by the COR as required by the constitution—it was created by the interim government that oversaw Iraq’s transition before the constitution was ratified. This supposedly interim FSC ought to have been replaced very soon after the constitution was in place, but fifteen years later, the COR has yet to pass the necessary legislation—a failure that remains among Iraq’s foundational postwar sins.

In addition to a long track record of highly questionable rulings (see below), the FSC was completely disabled in 2019 after one of its members retired. The court had previously struck down articles in Law No. 30 that allowed for naming judges to the FSC, so no replacement judge could be appointed. Unable to achieve the quorum needed for rulings, the court has essentially been deactivated ever since.

Earlier this month, the COR finally embarked on the long-delayed effort to pass the constitutionally mandated legislation and create a new FSC. Yet the bill faced two tall obstacles. First, in today’s fractured politics it is nearly impossible to garner the two-thirds majority vote needed to pass such a law given its constitutional nature. Second, heated disagreements erupted over interpreting ambiguous constitutional language about the role of clergy at the FSC. After prolonged wrangling, the COR reverted to an easier but legally problematic option: continuing to postpone the creation of a new, constitutionally compliant FSC and instead amending Law No. 30 in ways that reactivate the existing FSC, since this required only a simple majority.

Specifically, the amendment stipulates that all current FSC judges be removed and new ones be appointed. The court’s jurisdiction has been expanded as well. Ironically, the amendment is selectively copy-pasted from the constitution—the powers and jurisdictions contemplated for a constitutionally compliant FSC are repeated word for word, but the articles that set out the process and requirements for establishing such a court are entirely ignored.

Another problem is that the amendment’s process for nominating judges is vague and unaccountable. It empowers only some judicial bodies to make a list of nominated judges and send it to the president for ratification and swearing-in, or to the COR should the president refuse. The amendment also tries to inject ethnosectarian “balance” into the FSC’s makeup, and establishes a new but ill-defined position of secretary-general for the court.

Regardless of how these changes pan out, the FSC has already lost a great deal of credibility over the years by passing politically motivated and undemocratic judgments on various issues. For example, it reduced the COR’s powers and subverted independent commissions to the executive branch. It hastily issued a decision on the unconstitutionality of the Kurdistan independence referendum, yet remained silent when the Iraqi government missed the 2007 deadline for implementing Article 140 of the constitution, which covers disputed territories. Perhaps most damaging of all in reputational terms, the court has interpreted constitutional articles in ways that favored the ruling party at the time—a power it was never granted under Law No. 30. In 2010, for example, it interpreted the meaning of “winning bloc” from Article 76 (1) in a manner that favored Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, despite clear evidence that a different interpretation was intended during the constitutional drafting process.

Elections, Energy Disputes

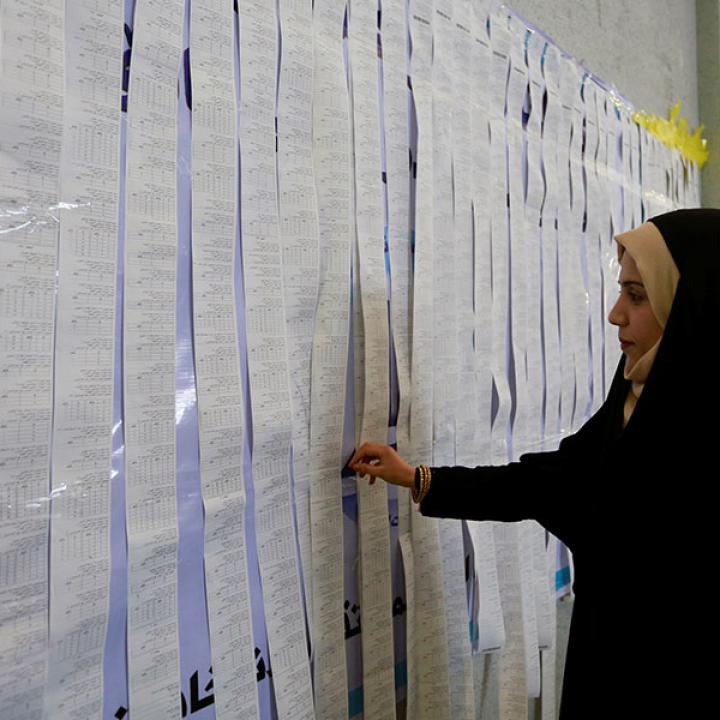

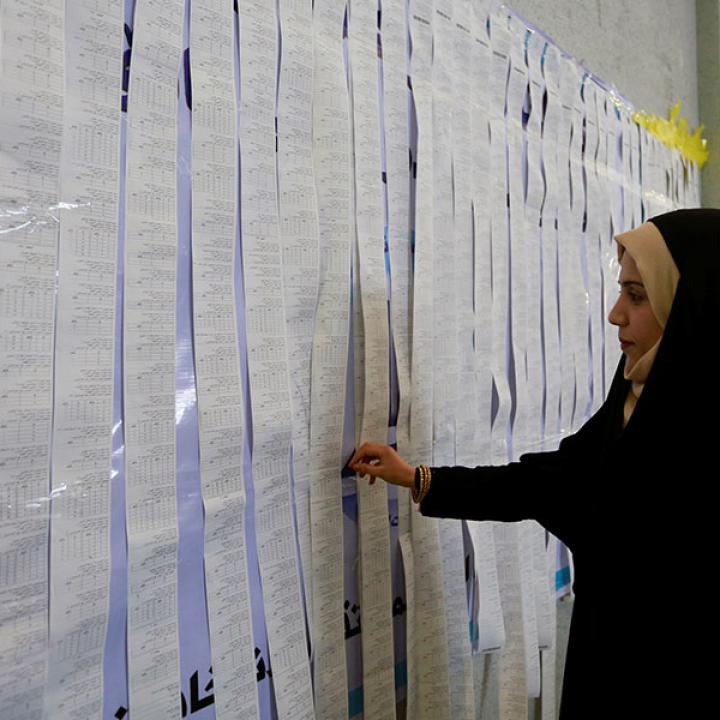

Once the new FSC justices are in place, the most immediate and important issues requiring their attention will be the coming elections and the petroleum management disputes between the KRG and the federal government. The public has demanded early elections, and the government has committed to hold them this October. If the COR elected in that vote is to be legally valid, the FSC must ratify the results. Alternatively, the court could throw a wrench into the election gears by ruling that parts of the new electoral law are unconstitutional. Other political issues that the FSC might immediately look into are the 2021 budget law and the COR’s legally disputed January 2020 vote on expelling all foreign troops.

Regarding energy disputes, Baghdad filed an FSC case against the KRG in 2012 over the region’s independent oil exports. The case stalled for technical and political reasons, but in 2014, the government filed a separate case against Turkey at the International Chamber of Commerce’s International Court of Arbitration, accusing it of allowing KRG oil exports via the Iraq-Turkey Pipeline without Baghdad’s green light. The fate of the two cases may be related—Iraqi-Turkish tensions over the pipeline would decrease if the FSC issues an export ruling that the KRG and Baghdad both respect, though this is unlikely. Ankara wants Baghdad to drop the arbitral case and focus on putting Iraq’s legal house in order regarding petroleum management. The government attempted to do so in the past with the Iraqi National Oil Company Law, but the FSC ruled it unconstitutional.

Policy Recommendations

Although Iraq can take some pride in its constitution and competitive politics, a legal and political culture of constitutionalism and rule of law has yet to take root. The potential pitfalls in the COR’s amendment of Law No. 30 signal that the political system still faces serious challenges to its functionality and legitimacy. As it has done in the past, the reactivated FSC might overstep its role and set precedents that affect the country for years to come. Militias and corrupt politicians have been chipping away at Iraq’s sovereignty by flaunting rule of law in many sectors, and the judicial branch is no exception. The United States should watch this space.

In general terms, Washington’s goal should be for Iraq and its judiciary to respect their own constitution. And as crucial elections near, the Biden administration (via the Justice Department’s office inside the Baghdad embassy) should work with international partners on engaging with the FSC. This includes offering technical and legal assistance as well as inviting the new judges to Washington in the near future (albeit after the coronavirus pandemic). U.S. officials should also stand ready to call out any bogus election results and the governments they produce. If the FSC rubber-stamps electoral procedures or results that are neither free nor credible, it risks being perceived as an extension of the political class and its patronage system. Alternatively, fostering trust in the electoral system and the high court could help boost voter turnout come October. Finally, a legitimate and respected FSC is crucial to Washington’s call for resolving federal-KRG disputes on energy and other matters according to rule of law rather than political facts on the ground.

Safwan Al-Amin is an international attorney studying at Yale Law School. Bilal Wahab is the Wagner Fellow at The Washington Institute.