- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

The Palace Intrigue at the Heart of the Qatar Crisis

Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are probably trying to groom an alternative and more pliable al-Thani, as compared to the current emir and "father-emir," for a leadership role.

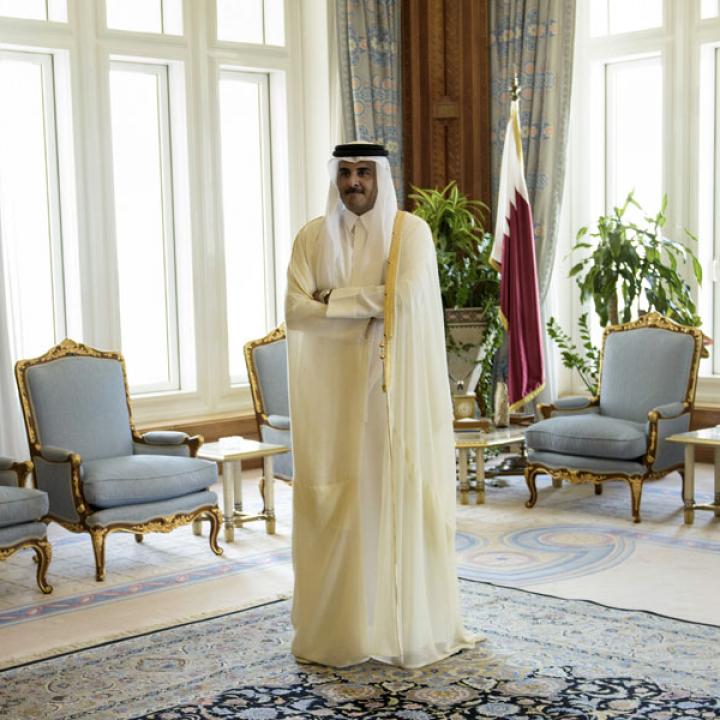

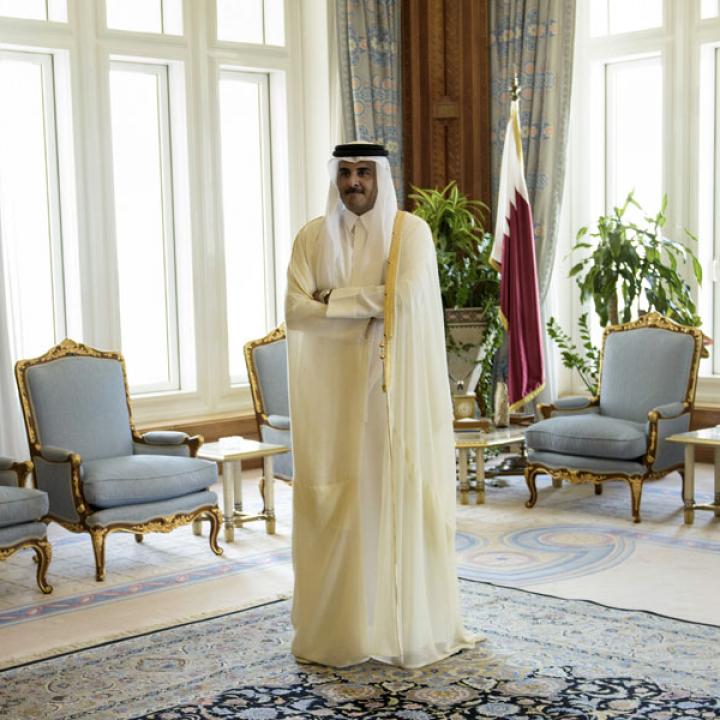

Who is the real leader of Qatar? On paper, it is Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, the 37-year-old son of Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, who abdicated in Tamim's favor in 2013. But the leaderships of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which have become involved in a messy diplomatic squabble with Qatar, think it is actually Sheikh Hamad, now known as the "father-emir," who is still pulling the strings. The truth could dictate the outcome of the Gulf crisis, for which the United States is trying to broker an early settlement while Iran watches mischievously from the sidelines.

There are a variety of judgments of who is really in control in Doha, none of which are particularly complimentary to the Al Thanis, the onetime desert tribe that number a mere few thousand but effectively own the world's third-largest reserves of natural gas.

"Hamad dislikes the Emiratis and the Bahrainis, but completely loathes the Saudis," was the opinion of a former diplomat who lived in Doha for several years, who insisted that the father is still the driver of Qatari diplomacy. The 65-year-old Hamad apparently takes a historical and "intensely personal" perspective. Standing in a room festooned with ancient maps, he once lectured a visiting British defense minister for five consecutive days on the historical links of the Al Thani to distant locations, now mostly in Saudi Arabia. Hamad, in the judgment of a onetime insider, is "forceful" and "dangerous."

Those with a less intimate acquaintance with the Al Thani family take a more benign view. "Tamim is willful, but his father is a restraining force," is the judgment of one European official involved in Qatar's 2022 hosting of the World Cup, which involved billions in infrastructure building on top of the alleged bribes paid to be chosen as a venue, estimated by a European intelligence agency at $180 million.

Such an amount is almost pocket change for Doha. Qatar's gas has given it the highest gross domestic product per capita in the world. During his reign, Hamad leveraged that wealth to set up Al Jazeera, the region's first satellite television network, which dramatically increased Qatar's influence -- while upsetting its neighbors because it provided a platform to opposition voices and troublesome preachers like Islamist cleric Yusuf al-Qaradawi. Over the years, Hamad was unmoved by diplomatic protests at the station's output, often blandly and incredulously responding to a range of ambassadors that Al Jazeera was either independent or should be allowed freedom of expression.

Hamad, it appears, cannot resist an opportunity to annoy his Gulf Arab neighbors, even if this risks the breakup of the Gulf Cooperation Council, which has largely protected the conservative Arab monarchies and sheikhdoms from the region's turbulence since the Iran-Iraq War broke out in 1980. The examples of Hamad poking his neighbors in the eye are legion. Early in the Syrian civil war, Qatar tussled with Saudi Arabia over which would back the most effective jihadi fighters. Doha has also supported the Muslim Brotherhood as the wave of the future for the Muslim world, an ironic position considering that the Brotherhood disapproves of hereditary sheikhdoms like, er, Qatar.

Hamad's antagonistic relationship with his Arab neighbors extends to the first days of his rule. After he pushed his own father to the side in 1995, the Saudis and Emiratis, with some Bahraini involvement, tried to organize a counter-coup. Several hundred tribesmen were recruited, and at least one arms dump was established in the desert. The plot failed because one tribesman informed Hamad's court of the plot. But to Hamad's disappointment, any condemnation by the United States was muted so as not to upset the Saudis, the larger and more important regional ally.

Washington's concern for Riyadh's feelings went unrewarded. In 2003, the Saudis withdrew permission for the U.S. Air Force to use the Prince Sultan Air Base. Qatar had built the giant Al Udeid Air Base essentially for just such an opportunity. U.S. military aircraft have flown from it during operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as against the Islamic State.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain, along with Egypt, are leading the attempt to isolate Qatar by cutting off air links, restricting shipping, and closing the overland route via Saudi Arabia. They have produced a list of 13 demands and given Qatar until July 2 to accept them. It was more time than Doha needed -- this week, it rejected them all. The demands range from the apparently bizarre, such as expelling Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps personnel (Are there any there?) to the obvious -- expelling any political dissidents to their home countries in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, or Egypt. There's also the nigh impossible, such as closing down Al Jazeera, now a billion-dollar world-class brand viewable in hotels across the world.

Qatar does not appear to be adhering to its opponents' playbook, and insiders say Riyadh and Abu Dhabi were disappointed when Doha publicized the list of demands. The question is: What happens now?

In the slightly longer term, how Hamad and Tamim will respond depends on how much pressure they feel from the wider Al Thani clan. Hamad's leadership is not fully respected; Tamim's even less so. The former emir's 1995 accession to the throne was resented within the extended family, and the view lingers. Bloodlines are important to the Al Thani, so it is a negative that Hamad's mother was from the al-Attiyah tribe. Hamad is regarded, therefore, as only half Al Thani, a "cuckoo in the nest," in the words of one experienced observer. Two of Hamad's three wives are Al Thani, but his favorite -- and the mother of Tamim -- is the statuesque Moza, who comes from the al-Missned tribe. So Tamim's position within the Al Thani family is no more secure -- and arguably less secure -- than Hamad's. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are probably trying to groom an alternative and more pliable Al Thani for a leadership role.

In wider Qatari society, most probably don't want to be at odds with Saudi Arabia. Nor do they want to be dependent on Iran, which is serving as a route for food supplies no longer arriving via Saudi Arabia.

But domestic pressure for reconciliation may not be enough for Hamad to concede much, at least for now. His health could prove to be an important factor. Once very overweight, he is now much thinner but looks gaunt rather than healthy. His kidneys have been a problem -- diplomats think he has had at least one transplant.

In the current diplomacy, neither Hamad nor Tamim has had much of a public profile. But Hamad could well be enjoying the developing crisis. Several years ago, Hamad bin Ali, a young Al Thani with a reputation for being capable, was tasked with setting up a food security project. At the time, diplomats thought it was perhaps meant to deal with the danger of the Strait of Hormuz, at the mouth of the Gulf, being closed to shipping. Now it seems that the father-emir may have been forward planning. What other tricks does he have up his sleeve?

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Gulf and Energy Policy Program at The Washington Institute, and coauthor of its 2017 Transition Paper Rebuilding Alliances and Countering Threats in the Gulf.

Foreign Policy