- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 2915

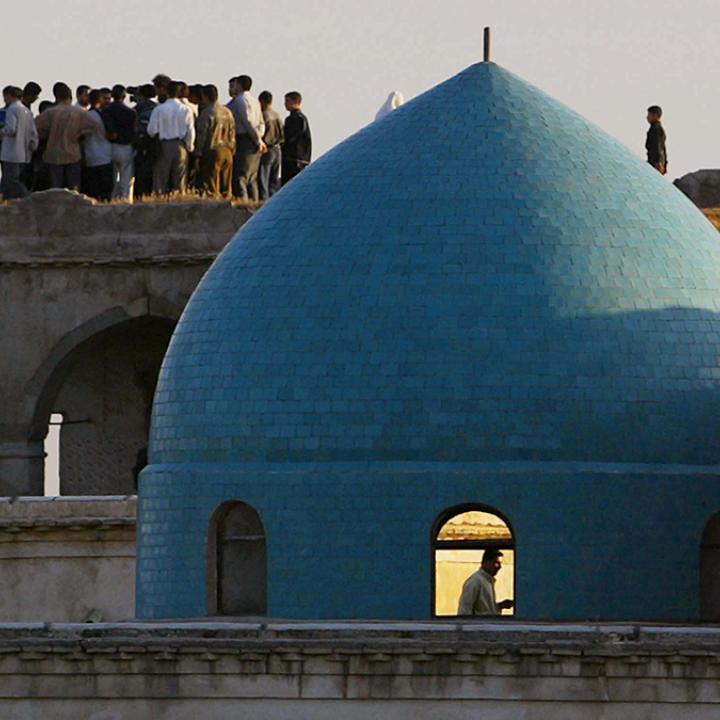

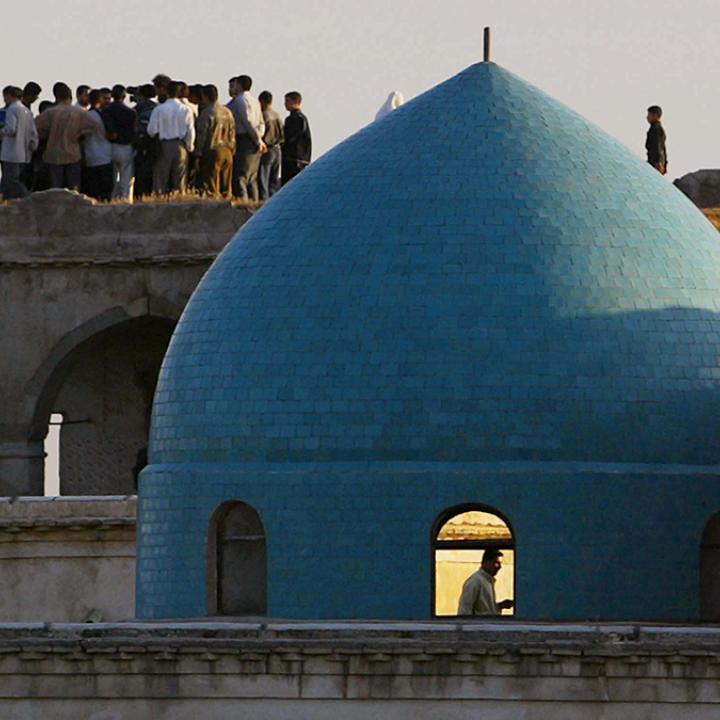

Setting the Stage for Provincial Elections in Kirkuk

The disputed area is more combustible than ever, but the United States still has time to press for consensus-based security and political decisionmaking.

On October 16, Iraqi security forces reentered the disputed oil-rich city of Kirkuk in strength for the first time since 2003, upending fourteen years of Kurdish domination there. Local governance is now deadlocked by a Kurdish boycott of the provincial council, while security has deteriorated due to a quick-developing Kurdish insurgency, the first of its kind since 2003. Every week, Kirkuk city witnesses more than half a dozen Kurdish attacks on Iraqi security forces, whether by rocket-propelled grenades, roadside bombs, mortars, or assassinations.

On May 12, the province is slated to hold local elections for the first time since 2005, but multiethnic Kirkuk is more of a powder keg than ever. To keep it from exploding, Iraqi and Kurdish authorities need to defuse tensions quickly and reach a sustainable balance—and they will need some outside help.

STATUS QUO UPENDED

Since the fall of Saddam Hussein, Iraq has held provincial elections on three occasions: 2005, 2009, and 2013. Yet Kirkuk province—which has a special disputed status under coalition statutes and Article 140 of the Iraqi constitution—has not held one since 2005. Subsequent local polls were canceled there for a variety of practical and political reasons. Kurdish blocs in the federal parliament repeatedly prevented the passage of provincial election regulations that would allow Kirkuk to participate. Specifically, they opposed the idea of dividing the provincial council equally among the area's three main ethnosectarian communities, with Arabs, Turkmens, and Kurds each receiving 32 percent of the seats and Christians claiming the other 4 percent (Kirkuk's actual ethnic composition is a subject of heated debate).

As a result, governance in Kirkuk has been frozen in the shape set by the January 2005 elections, when many Sunni Arabs boycotted the polls and a coalition of Kurdish parties won twenty-six of the forty-one provincial council seats. Kurds have since held an unassailable majority on the council, and the province has been overseen by a Kurdish governor and Kurdish police chief the entire time.

This status quo has been under threat in recent months, however. On September 14, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi asked the parliament to impeach Kirkuk governor Najmaldin Karim, who was later forced to flee the province when federal forces evicted Kurdish Peshmerga there a month later. Both Najmaldin and Rebwar Talabani—the provincial council chair who hails from the Kurdistan Islamic Union—also face legal challenges related to the Kurdistan Regional Government's decision to extend its September independence reference to disputed Kirkuk. The province's long-sitting deputy governor, Arab politician Rakan Saeed al-Jubbouri, has functioned as acting governor since October, though Talabani will likely be replaced by a different Kurdish candidate, Jwan Hassan.

The council has been unable to convene since the October military operations because a quorum of twenty-one members is needed, and all twenty-six Kurdish members are boycotting. Some of them have declared that the council cannot meet in Kirkuk while it is under federal military occupation.

As for the province's security situation, such matters were coordinated through a committee chaired by the governor after local Iraqi army forces collapsed in June 2014. The committee received key inputs from Peshmerga commanders and provincial police chief Brig. Gen. Khattab Omar Aref, a Kurd form Kirkuk city, while Kurdish authorities assumed full control of local oil fields. Since October, however, a new Kirkuk Operations Command has been established at the province's old K-1 federal military base, led by Maj. Gen. Ali Fadhil Omran, an Arab member of the Badr Organization and former head of the army's Diyala-based 5th Division. Alongside General Omran, day-to-day control of federal forces in the area is exercised by Maj. Gen. Maan al-Saadi, commander of the Iraqi Special Operations Forces 2nd Brigade. For the most part, though, federal army and police forces have kept out of Kirkuk city since October 16, as have Kurdish security forces.

U.S. POLICY OPTIONS

On October 20, the U.S. State Department firmly reminded all parties of the need for shared governance in Kirkuk and other disputed areas: "The reassertion of federal authority over disputed areas in no way changes their status—they remain disputed until their status is resolved in accordance with the Iraqi constitution. Until parties reach a resolution, we urge them to fully coordinate security and administration of these areas." Since then, the U.S.-led coalition has maintained a small military advisory mission at K-1. Washington should now lay the rhetorical and practical foundations for longer-term U.S. policy on Kirkuk.

Preserving basic security is the first priority. From 2003 onward, the United States took great pains to reduce the risk of intensified ethnic conflict in Kirkuk, investing diplomatic and military capital to put a cap on escalation risks. In 2010, for instance, the U.S. military established the trilateral U.S.-Iraqi-Kurdish Combined Security Mechanism to reduce tensions during national elections held in the area that March. The CSM required U.S. forces to jointly patrol and maintain checkpoints on Kirkuk's dangerous streets.

Current conditions are clearly different from the days when over 100,000 U.S. troops were present, but the need for an international military observer and coordination function in Kirkuk has not diminished. A Joint Security Mechanism should therefore be established, with a senior working group that pulls in the governor's office, provincial council, and UN Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI). In addition, a Combined Coordination Center should be collocated with the Kirkuk Police Service headquarters at the regional air base in Kirkuk city for the purpose of bringing federal, provincial, and Kurdish forces together. The initial focus of this new mechanism would be developing better cooperation ahead of this year's planned elections.

The issue of whether, when, and how to hold provincial elections in Kirkuk is more complex. In keeping with the scaling of seats by population size enacted nationally since 2005, any new elections would see Kirkuk's council seats reduced from forty-one to fewer than thirty. Moreover, national election results from Kirkuk in 2006, 2010, and 2014 suggest that Kurdish factions would win a plurality or very slender majority of these seats—certainly not the commanding position they maintain today.

Some observers may worry that such drastic political changes could create a dangerous brew of highly competitive local elections that risk being viewed as an ethnic census. Viewed another way, Kirkuk's council has needed refreshing for a long time, and a more balanced membership might produce consensus candidates for governor and council chair. If unstructured elections are considered too risky, the provincial elections law could return to the aforementioned 32-32-32-4 percentage split between ethnic blocs.

Whatever the case, the United States and UNAMI should encourage Iraqi federal legislators to include arrangements for Kirkuk in the draft provincial elections law they are currently amending. The parliament has asked for the Kirkuk council's input on the matter, but none can be given until the local body reconvenes. Therefore, another high priority for Washington and UNAMI is reactivating the Kirkuk council—which cannot happen until Kurdish members receive reassurances that they will not be arrested for their role in the KRG referendum or related charges. Once the council meets, it can also elect a new governor, most likely a Kurd. All of these tasks will be easier if the Kurds see evidence of internationally observed security coordination.

In the longer term, the coalition should not forget the fundamental ethnic compact written into Article 140 of the Iraqi constitution, which called for resolution of property and residency disputes, a census, a referendum on Kirkuk's administrative future, and potential boundary changes. The charter also clearly states that Kirkuk's oil fields are to be administered by the federal government, so all parties should agree to this condition during U.S.-backed negotiations. As the country's former occupier and the midwife to its constitution, the United States has a special responsibility to ensure that Iraqis resurrect the commitments enshrined in Article 140 when tackling disputes over Kirkuk and other areas. Prior to the 2011 military withdrawal, Washington maintained a consulate at Kirkuk Regional Air Base and evaluated the option of keeping a diplomatic station there afterward, as occurred in Basra and Erbil. This option might be worth reconsidering in light of the pivotal developments in Kirkuk, where the risk of an Islamic State resurgence and new fighting between federal and Kurdish forces justifies a sustained U.S. observation mission.

Michael Knights, a Lafer Fellow with The Washington Institute, has worked in all of Iraq's provinces and spent time embedded with the country's security forces. Bilal Wahab is a Soref Fellow at the Institute.