- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3987

So Far So Good? The Israel-Lebanon Ceasefire Is Largely Holding

The agreement’s implementation phase is going surprisingly well and has been extended, but maintaining the ceasefire will require officials to resolve the issues in dispute and address Hezbollah’s threats.

The Israel-Lebanon ceasefire that went into effect on November 27 called for a sixty-day implementation period ending on January 26. There have been almost no exchanges of fire during that time, and many of Hezbollah’s military capabilities have been dismantled. Before the deadline, Jerusalem announced it would delay the withdrawal of the Israel Defense Forces due to gaps in Lebanese enforcement, and Washington then issued a short extension to which Beirut agreed. On January 26, however, Hezbollah encouraged a rushed return home by south Lebanese villagers, leading to a lethal IDF response. Indeed, the agreement and its parties will be put to the test repeatedly in the near future.

The Agreement and Side Letter

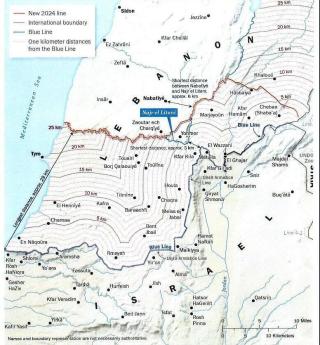

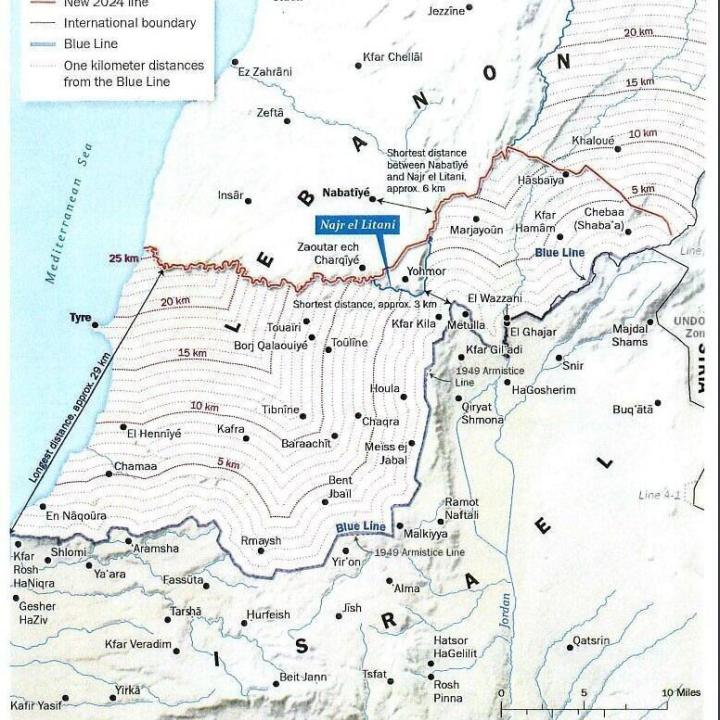

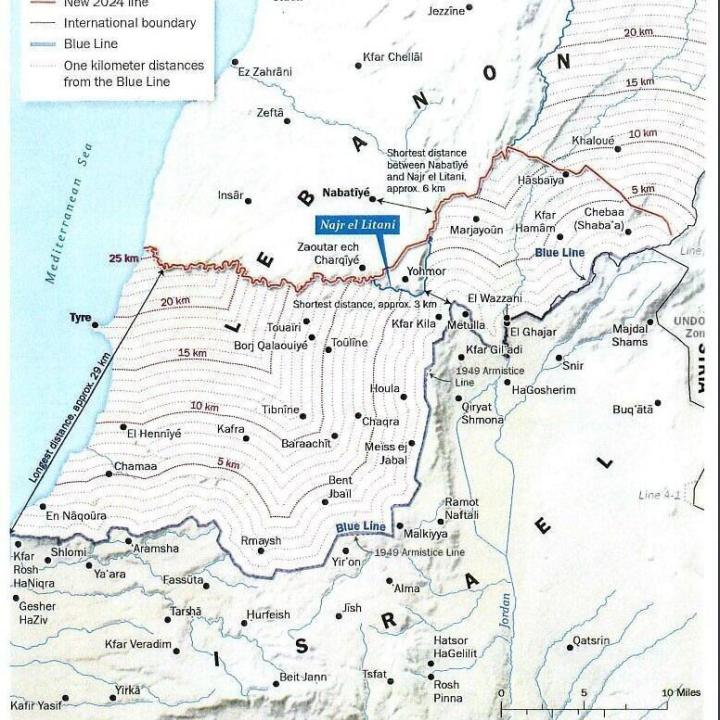

The ceasefire agreement included the establishment of a U.S.-led International Monitoring and Implementation Mechanism (IMIM) with the participation of Israel, Lebanon, France, and the UN Interim Force in Lebanon. It also stipulated that during the sixty-day implementation period, Israel and Hezbollah would gradually withdraw from southern Lebanon, and the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) would deploy throughout the area with UNIFIL’s support and dismantle Hezbollah’s arms there. Attached to the agreement was a map of the relevant area, mostly south of the Litani River but expanded to the north by several kilometers in the area opposite Metula.

In a side letter to Jerusalem, parts of which were leaked, Washington pledged to allow Israel to respond to threats in accordance with international law and act at any time against violations in southern Lebanon. In the rest of Lebanon, it was allowed to respond to Hezbollah violations that the LAF does not address, after notifying the United States. Washington also pledged the following: to prevent Iran from establishing itself in Lebanon and undermining the agreement; to provide Israel with intelligence on violations and on Hezbollah’s penetration of the LAF; and to recognize Israel’s right to conduct reconnaissance flights over Lebanon as long as they do not break the sound barrier.

Initial Implementation Period

The IMIM was established in late November, headed by Maj. Gen. Jasper Jeffers of U.S. Central Command and American mediator Amos Hochstein, with the participation of Brig. Gen. Guillaume Ponchin of France, Brig. Gen. Edgar Lowndes of the LAF, and Brig. Gen. Amit Adler of the IDF. These parties met four times to discuss implementation of the agreement, and according to informed sources, UNIFIL was somewhat marginalized as the center of gravity shifted from the UNIFIL-hosted tripartite meetings held since 2006 to the much more substantial bilateral channels with the United States, which has CENTCOM representatives in both Beirut and the IDF’s Northern Command in Safed.

During the ceasefire, Israel has responded forcefully to Hezbollah violations—apparently after informing the IMIM—destroying dozens of military sites and killing about fifty Hezbollah fighters who came south or tried to remove weapons from the area. In mid-January, Israel reported that the IMIM had addressed 65 percent of the complaints submitted to it, and that Israel had responded to violations not addressed by the LAF within seventy-two hours. According to IDF statements, all Israeli strikes were in accordance with the agreement and were intended to remove threats.

Only 10 to 25 percent of the displaced residents of northern Israel have returned home. The government has offered them financial incentives to return by March 7, which will be reduced after that date. In southern Lebanon, the IDF is preventing the population from returning to villages near the border.

The LAF has mobilized six thousand soldiers and begun deploying in places evacuated by the IDF. LAF units have also reportedly carried out about five hundred missions to expose Hezbollah sites and dismantled most of the group’s military infrastructure south of the Litani without resistance. According to UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres, UNIFIL has uncovered more than one hundred arms caches belonging to Hezbollah and other groups since November 27. It is unclear how the LAF is handling weapons it confiscates to ensure they will not be returned to Hezbollah, as so often happens in Lebanon. Meanwhile, senior Lebanese officials have complained of widespread violations by Israel on the ground and in the air.

The Palestinian terrorist groups Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and Fatah al-Intifada have handed several military bases over to the LAF in the Beqa Valley and other areas—a possible first step in disarming them. Lebanon also conducted a well-publicized search of Iranian diplomatic luggage at Beirut’s airport in an attempt to show control of its borders. In addition, Syrian authorities reportedly intercepted two Iranian arms shipments to Hezbollah that were transiting through their territory.

Hezbollah was forced to accept the ceasefire agreement due to its postwar weakness, and since then has taken a verbally critical but operationally cautious approach to continued heavy damage inflicted by Israel. The group has avoided responding to casualties other than firing two mortar shells on December 2, and has not responded to U.S. drones launched from Israeli territory or operated by UNIFIL, which it has defined as a red line in the past.

Hezbollah’s opposition to the new situation stems not only from Israel’s actions, but also from its own particular understanding of the terms of the agreement—or, rather, from denial. Hezbollah spokesmen repeatedly emphasize that the agreement is only an implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1701 and relates solely to the area south of the Litani, disregarding the map that is part of the agreement as well as its requirement that the group disarm. Outgoing prime minister Najib Mikati has argued that the map, which includes an area north of the river, is not part of the agreement. Yet President Trump’s Middle East advisor Massad Boulos has stated that “there is a misunderstanding, especially on the part of Lebanon” and that “according to the agreement, all armed groups must be dismantled, including Hezbollah, and this task is assigned to the Lebanese army—including north of the Litani.” Hezbollah has already begun efforts to rebuild the south, while Israel considers every house previously used for military purposes to be terrorist infrastructure that should not be rebuilt.

The Sixty-Day Deadline, Extended

The main issue on the Lebanese agenda now is Israel’s withdrawal. From the start of the ceasefire, Israel questioned the LAF’s ability to fulfill its obligations within sixty days, and thus its own ability to withdraw by then. It also considered retaining control of several commanding heights in southern Lebanon.

Israel announced on January 24 that its gradual withdrawal will continue beyond day sixty, as Lebanon has not yet fully enforced the agreement. The delay will allow the IDF to continue destroying Hezbollah infrastructure, capturing arms, and reassuring residents of northern Israel as their return date approaches. It also demonstrates that there is some flexibility in the agreement, allowing adaptations as the situation evolves. On January 26, the White House announced an extension of the agreement until February 18, adding that negotiations will begin for the return of Lebanese prisoners of war.

Hezbollah, while threatening to resist the “occupation forces,” has avoided committing to a timeline or method. When Israel indicated that its withdrawal would be delayed, Hezbollah placed responsibility on the Lebanese government and blamed diplomacy for failing to defend Lebanese sovereignty. The only solution, Hezbollah insists, is its triad of “people-army-resistance,” which is being jeopardized by the ceasefire agreement and by President Joseph Aoun’s inauguration speech calling for the state’s monopoly on arms.

In addition, Hezbollah has sought indirect friction by encouraging southern villagers (and probably its own members) to swarm southward. Since January 26, twenty-six Lebanese have reportedly been killed while approaching IDF units. The LAF, meanwhile, called on the villagers not to return yet, then made feeble attempts to stop them, and finally assumed the role of protector while avoiding confrontation with the IDF.

Conclusion

Surprisingly, implementation of the ceasefire has been relatively successful so far—a testament to Israel's achievement and Hezbollah’s defeat. The IMIM and its American leadership have been somewhat successful in energizing the LAF and UNIFIL and have also given Israel leeway to respond directly to Hezbollah’s violations and extend the implementation phase. Hezbollah has refrained from responding forcefully to these developments, focusing its energy on political and information efforts while debating whether and how to stop the erosion of its position and when to use its remaining forces. Its weapon of choice on day sixty was popular pressure, sending civilians toward the IDF and undermining the Lebanese government.

The immediate challenge will be maintaining the ceasefire after February 18. It is also clear that Hezbollah will take advantage of any dispute to challenge Lebanon’s new president, prime minister, and government, claiming that they are failing to defend the country and its sovereignty. Later, the group may seek to regain relevance by using force. Despite the current coordination between the United States and its close ally Israel, ongoing tactical friction could potentially create tension between them.

Recommendations

The ceasefire must be maintained while agreement is sought on the issues in dispute, as long as Hezbollah’s threats are addressed. Israel must also maintain close strategic coordination with the United States while insisting on its security interests. When there is tension between time-related and performance-based milestones, it is important to focus on the latter, promoting three strategic goals:

- Removing Hezbollah’s threats against Israel, the United States, and Lebanon for the long term, especially in southern Lebanon.

- Promoting Lebanese sovereignty and a government monopoly on arms.

- Working toward a permanent ceasefire down the road.

The strategic horizon for Israel and Lebanon should be peaceful relations, and conditions for achieving this goal should be patiently pursued. In addition:

- Implementation of the agreement after Israel’s withdrawal must be ensured. The Lebanese government must publicly instruct its army to fulfill its commitments and disarm Hezbollah, initially in southern Lebanon. It must also demand that UNIFIL act to fulfill its mandate—both independently and alongside the LAF, including in areas Lebanon has tried to define as “private property” and off limits.

- Any assistance to Lebanon and aid to the LAF must be conditioned on the fulfillment of their obligations under the ceasefire agreement and Resolution 1701.

- UNIFIL must adapt its operations and procedures to the new situation, improve its situational awareness, and play a proactive role in discharging its mandate.

- The United States, France, and Israel should prepare for a review of UNIFIL’s mission fitness, size, and budget, with an eye toward the next mandate renewal scheduled for late August.

Brig. Gen. Assaf Orion (Res.) is The Washington Institute’s Rueven International Fellow, a senior research fellow at the INSS, and former head of the IDF Strategic Planning Division.