- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4008

Syria’s Quest for Oil May Include Russian Shipments

As the new government looks for quick answers to its emergency energy needs, it may turn to sanctioned Russian ship operators and other illicit actors.

To address the acute energy crisis it inherited from the Assad regime, Syria’s interim government has been working swiftly to procure more oil shipments. Its options are limited, however, since major international trading firms and ship owners remain reluctant to risk running afoul of Western sanctions. The EU recently “suspended” restrictive measures in key sectors like energy, and the previous U.S. administration issued temporary waivers for transactions that meet essential human needs. Yet it will take time for these measures to have an impact on shaky market sentiment amid uncertainty surrounding U.S. sanctions.

In these circumstances, some opportunistic traders and ship operators will likely be more willing than others to do business with Syria—including Western adversaries like Russia, which is familiar with the country’s energy sector and seeks to maintain a foothold there after withdrawing much of its presence post-Assad. In the past two weeks alone, a pair of Russia-linked, U.S.-sanctioned ships have been tracked en route to Syrian ports (see below). Washington and its European partners should therefore pay close attention to the nature of any suppliers that attempt to meet Syria’s urgent oil and energy requirements. The entire sector has been crippled by fourteen years of war, and rebuilding it under new authorities must be done the right way if officials hope to avoid the structural failures seen in neighboring countries over the decades.

Russian Oil Activity Post-Assad?

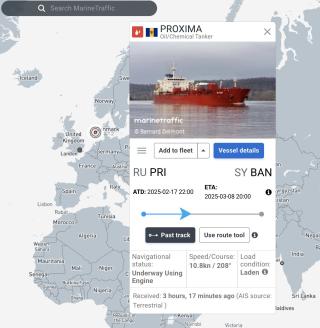

On February 23, the Barbados-flagged tanker Proxima (IMO identification number 9329655) changed the destination in its automatic identification system (AIS) from Mersin, Turkey, to the Syrian port of Baniyas while sailing from Russia. This course change was detected using data from MarineTraffic, and the observation was confirmed by ship trackers at Lloyd’s List Intelligence and TankerTrackers.com. On February 26, the ship switched its AIS destination back to Mersin, raising suspicions that it might be attempting to mask its destination.

The background of the Proxima—which is currently carrying an oil product, likely diesel—lends weight to these suspicions. The vessel is on the sanctions list maintained by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control and is linked to Fornax Ship Management FZCO, a firm based in the United Arab Emirates and connected to the state-owned Russian shipping company Sovcomflot. Amid Western sanctions, a fleet of such vessels has emerged to haul Russian oil to key markets, particularly India and China (Moscow’s top clients, as discussed recently by The Washington Institute’s Maritime Spotlight) and Turkey (which has become a key importer and re-exporter of Russian diesel). Indeed, Russia is a major supplier for customers that need diesel for power generation, truck/machinery fuel, and other uses—a gap that urgently needs filling in Syria, too.

The final destination of the Proxima’s cargo remains unclear as of this writing; the ship has not reached Middle East waters yet and may not end up in Syria. Earlier today, however, AIS data indicated that another Russia-linked, U.S.-sanctioned tanker—the Prosperity (IMO 9322956), previously known as NS Pride—arrived off the coast of Baniyas, most likely carrying diesel loaded at Russia’s Primorsk port, according to Kpler. Satellite imagery is often required to fully confirm the locations of certain sanctioned tankers in case they are involved in obfuscation schemes, but in this case both MarineTraffic and TankerTrackers.com confirmed that AIS data showed Prosperity in Syria as of March 5; their finding will be further confirmed once a satellite image is available. Currently under sanctions related to the invasion of Ukraine, the ship is registered to Barbados—a practice used by many ship operators that trade sanctioned oil from suppliers like Russia and Iran.

More important, long-time experts on oil flows to the Assad regime (e.g., Samir Madani of TankerTrackers.com) believe that Moscow could send oil shipments to the new government in return for maintaining Russian military bases in Syria. Meanwhile, a March 3 media report stated that Damascus had secured a light crude shipment to be refined in Syria, and that it is scheduled to arrive in a few weeks.

Syrian Oil Product Imports: Trends and Limits

The Baniyas terminal has several berths designated for different types of oil, such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), crude oil, gas oil/diesel, and gasoline. Tankers that docked there prior to the Assad regime’s collapse included crude cargoes from Iran, previously Syria’s top supplier of seaborne oil. According to Kpler, Syrian oil imports from Iran averaged 55,000 barrels per day last year, via one to two monthly shipments by Suezmax vessels. These shipments provided key refinery feedstock, yet it remains to be seen how Damascus will resume a substantial supply line of seaborne crude for its two main refineries, Baniyas (the largest) and Homs.

For now, seaborne LPG shipments—which are urgently needed for heating and cooking—appear to be flowing more than other oil products. Most of them come from Dortyol, Turkey, a longtime clandestine source during the Assad era. One LPG tanker, the Palau-flagged Gas Catalina (IMO 9183568), sailed to Baniyas from Dortyol at least three times in February alone. This vessel is reportedly linked to the India-based company Hamburg Marine Lines. On March 1, Gas Catalina left Dortyol signaling for Beirut, Lebanon, but it most likely went to Baniyas. Another LPG tanker was observed signaling for Lebanon’s port of Tripoli, yet it bears watching given the past track record of some tankers signaling one destination but then ending up in Syria instead while masking their final destination. Moreover, the Liberia-flagged LPG tanker Gas Husky (IMO 9507764)—part of the fleet of Greece-based Stealth Maritime Corporation—left Dortyol on February 26 signaling for Baniyas.

Regarding diesel, the Syrian Arab News Agency announced that a tanker carrying the much-needed “mazut” arrived at Baniyas on February 27, without revealing the name of the vessel or its source. Data from S&P Global Commodity Insights indicates that the country’s total oil demand may average around 100,000 barrels per day in the near term, the majority of it diesel/gas oil (though such estimates are limited by the fact that the government will need more time to complete the difficult postwar task of updating its energy databases).

Tellingly, interim Syrian oil minister Ghiath Diab revealed in January that oil cargoes are being “imported from private companies” and have not been procured “in the form of international agreements and contracts,” indicating a lack of government-to-government supply contracts. He added that private firms are allowed to import oil and offload in Baniyas, but not to distribute it. For now, the nature and role of the local companies involved in the import process remain unclear, as does the process itself.

Regarding land routes, Damascus has reportedly resumed an “amended” arrangement with the Kurdish administration in northeast Syria to receive crude and other oil supplies from Kurdish-controlled fields—a deal that dates back to the Assad regime. Yet the amounts in question are estimated to total just 5,000 barrels per day—not nearly enough for Syria’s needs. During the Assad era, some Kurdish crude transfers were reportedly carried out by U.S.-sanctioned intermediaries such as al-Qatirji, a company that was also previously involved in facilitating Islamic State oil sales to the regime. The details of the amended Kurdish contract with the new government remain unclear, including the costs and agents involved.

In the meantime, Jordan started sending LPG to Syria via truck. Yet it will be challenging to find enough legitimate suppliers while halting the deep-rooted smuggling networks that bring gasoline and other oil products from Lebanon. Given Syria’s urgent demand, one can expect increased efforts to smuggle fuel from Lebanon so that it can be sold at higher prices on the Syrian black market.

U.S. Policy Implications

Postwar experiences in Lebanon (after 1990) and Iraq (after 2003) showed that the energy sector is particularly vulnerable to corrupt schemes that paralyze economic development. Post-Assad Syria urgently needs more funds and commodities to run basic public services, many of which were restricted during the Assad regime. If authorities do not figure out how to meet these needs and address market concerns about sanctions, several unfavorable scenarios could emerge:

- A limited number of suppliers could step in and monopolize energy supplies to Syria amid a lack of competition.

- Continued lack of clarity about U.S. sanctions relief could give established networks of traders and middlemen ample room to step up their operations—a potentially serious problem given that these networks are accustomed to operating under the highly corrupt Assad regime and generally do not serve U.S. interests. Monitoring these networks will therefore be crucial.

- To help maintain its footprint in Syria, Russia may seize the opportunity to strike unfavorable bargains with Damascus on matters like energy supply and currency shortages.

In light of Syria’s dire socioeconomic conditions, officials in Washington and Europe may argue for putting these concerns aside and urgently addressing the population’s needs with whatever means are available. Yet ignoring these problems carries a high risk of not only perpetuating the endemic corruption seen under Assad, but also empowering illicit networks and adversaries abroad.

Noam Raydan is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute and co-creator of its Maritime Spotlight series.