- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

From Torch to Tunis to El Alamein: Events 80 Years Ago Made the Modern Middle East

Also published in History News Network

The second week of November 1942 has much to tell us about the region’s geopolitical centrality, its enduring political currents, and its role in the future of the Jewish people—not to mention the evolution of American foreign policy.

The Middle East is again in the news. With nationwide protests in Iran, the schism in U.S.-Saudi relations and Israel’s fateful political election, it appears the region is again convulsed in tumultuous change. That makes it an appropriate moment to pause and reflect on how the Middle East we know today owes itself to events exactly eighty years ago, when the region passed through one of the most consequential, if largely forgotten, weeks of the last century.

The region has known many seismic moments over the past hundred years. From Allenby’s entry to Jerusalem (ok, nearly 105 years ago) to the world-shaking Suez Crisis to Khomeini’s overthrow of the Shah, the Middle East has been a setting for events that defined global politics. Each one of these moments—along with many others—not only changed the course of history but helped define the contours of the contemporary Middle East.

But there have never quite been so many historic events crammed into a single week as what happened eighty years ago. Students of Middle East history along with practitioners of Middle East policymaking should take a moment to consider the cumulative impact of three oft-forgotten events that all occurred within just days of each other, moments that forever altered the region’s landscape.

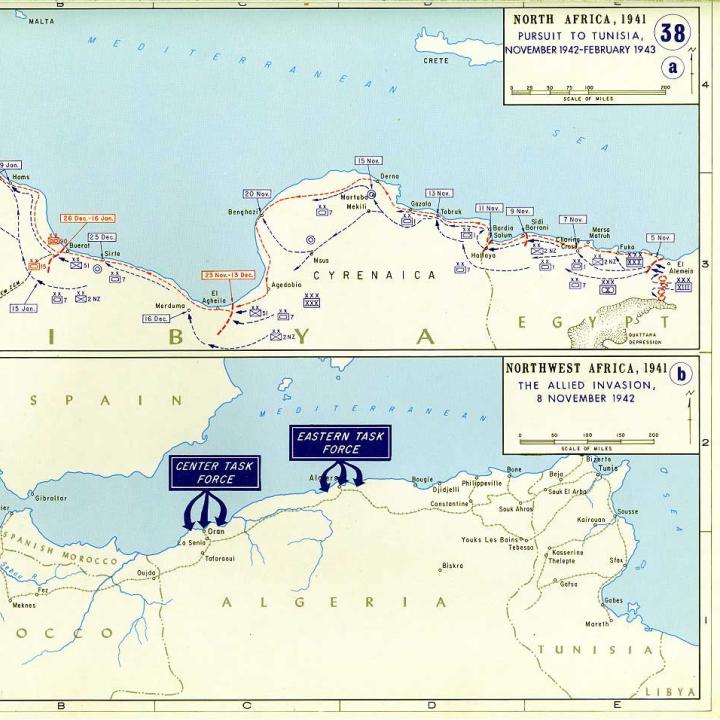

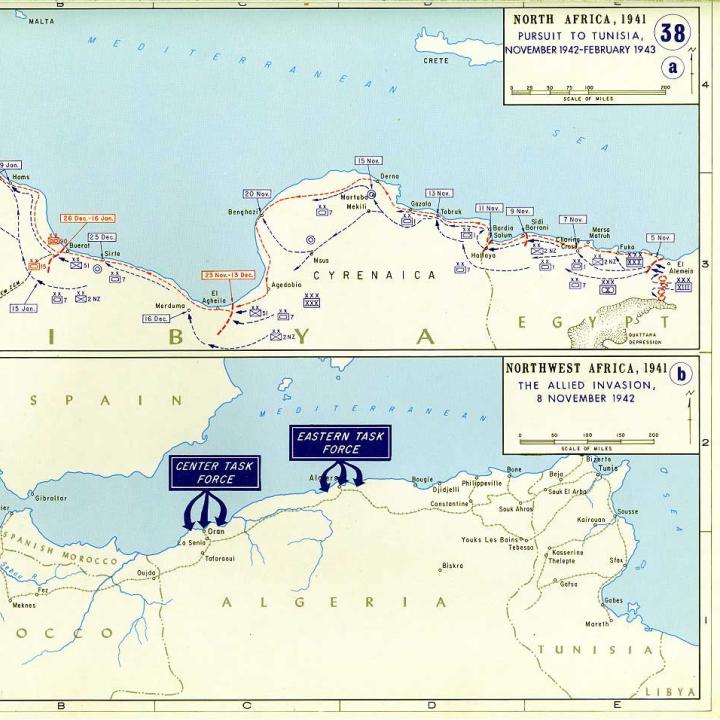

The fateful week begins at dawn on Sunday, November 8, with the launching of Operation Torch, the Anglo-American landing in Algeria and Morocco that was, at the time, the greatest amphibious invasion in human history. The first major U.S. combat operation of World War II, Torch marked the opening of a second front against Nazi Germany and a critical turning point in the war.

But did Torch leave a lasting imprint on the Middle East? Most observers say no. After all, American forces came and went, transiting through North Africa on their way to Italy, never to look back. But that’s precisely the point.

Torch underscored a strategic lesson that few contemplated when the United States declared war on Hitler’s Germany the day after Pearl Harbor—that victory in Europe would run through the sands of the Middle East. The region mattered little to America in the 120 years since the Barbary pirates gave us the Marines’ celebrated landing on the “shores of Tripoli,” but Torch marked the dawn of a new era in which the Middle East was a critical theater of strategic competition.

Here, Torch’s lesson was that America would henceforth ignore the region at its peril. Indeed, the Biden Administration may be the third in a row looking for ways to diminish America’s role in the region, but like his two predecessors, the incumbent president is finding that even with hot war in Europe and brewing conflict in Asia, America cannot escape the hold the region has on American interests and attention.

At the same time, America’s wartime leaders eighty years ago carved another principle into subsequent U.S. strategy by wanting little to do with the local politics of this obscure, distant and little-understood region. Washington showed itself especially allergic to involvement in the messiness of Middle East governance.

In retrospect, one could have imagined a different approach. After all, fifteen months earlier, U.S. and British leaders had issued the Atlantic Charter, declaring their common war aims to be to “respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live [and] to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them.” Within hours of landing in Algiers, the capital of French North Africa, U.S. commanders had the option of implementing those principles in the very first territory they captured from Axis forces.

But instead of bringing liberty to the liberated lands, they made a deal that empowered local Vichy administrators to maintain the reins of power in exchange for safe passage for U.S. troops. Rather than endorsing self-government and bestowing rights on “those who have been forcibly deprived of them,” U.S. commanders were eager to leave the business of local management to the Vichy colonialists they just defeated.

Those early U.S. decisions in Algiers in the hours after Torch laid the foundation for what became a core element of American Middle East policy. This is the instrumentalist idea that the region was a way-station to other U.S. policy aims, such as the defense of oil or the protection of critical sea lanes, but not intrinsically worthy of much political investment. Ultimately, this left the Middle East as the region of the world where America relies the most on friendly despots to help secure its interests.

For decades, through the Cold War and the “end of history” era that followed, this system worked well enough, though massaging the built-in pressures of these relationships was never easy. Now, as both ends of our domestic politics—the progressive left and the America First right—call for a shift in how we conduct this policy, that past uneasiness will pale in scope to the stress and anxiety likely to emerge from clashes with these traditional authoritarian partners. In this regard, current U.S.-Saudi tensions may just be a harbinger of things to come.

The second critical event to occur in this pivotal week eighty years ago was Monday, November 9, when Germany responded to Torch by invading Tunisia. Few today recall the six-month period after Torch when the most hotly contested territory in the European theater of war was not in Europe at all but in Tunisia, where Hitler deployed hundreds of thousands of troops ordered to hold the North African beachhead at all costs.

Fewer still recall Tunisia as the only Arab country to suffer a full-scale German occupation during the war. This included the dispatch of SS units, under the ruthless Walter Rauff, who applied his experience with mobile death gas vans used to kill Jews in Europe to implement round-ups, hostage-taking, concentration camps, deportations and executions of Jews in Tunisia. Despite the fact that the Germans never controlled more than a third of Tunisian territory, faced repeated military attacks by allied troops and were targeted almost nightly by allied bombers, the Nazis persisted in building the foundation for what would have been, if they kept their hold on Tunisia, the full persecution and execution of its Jews—the Final Solution was core to their mission here just as it was in Europe.

Driving the Germans from Tunisia was a tough slog. It took nearly as long for U.S., British and Free French troops to take Tunisia as it did, a year later, to move from the beaches of Normandy to the Battle of the Bulge. But after some missteps, the allies eventually routed the Germans in April/May 1943, taking about a quarter-million prisoners and setting up the invasion of Sicily and then mainland Italy the following September.

Few physical reminders remain of the German occupation. But the half-year of German control left a deep scar on the psyche of many Tunisian Jews, who only in recent years have emerged to tell their stories and demand their rightful chapter in the history of the Holocaust. As for broader Tunisian society, the German occupation ended with the return of the French protectorate and proved to be a brief detour on the road to eventual independence in 1956.

Yet here too, there is more to the story, as it marked the arrival of fascism in Arab lands. Indeed, the most lasting impact of the Nazi presence in Tunisia was to give Arabs an up-close look at a model of all-powerful government infused with supremacist ideology. Along with the 1941 arrival in Berlin of Jerusalem mufti Hajj Amin al-Husseini and Iraqi putschist Rashid Ali, both forced to flee from Baghdad, the Tunisia experience would play a role in building two movements that competed for power in the Middle East for decades to follow—the radical Arab nationalism of Gamal Abdul Nasser and Saddam Hussein and the Islamist extremism of Osama bin Ladin and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Whether both of these movements have been flushed from the Arab political system—or are just passing through a period of reassessment, retrenchment and rebirth—is one of the region’s most profound uncertainties.

The fact that Nazism itself did not spread throughout the Levant was thanks to the third event of this historic week, Britain’s success in the second battle of El Alamein, which concluded on Wednesday, November 11. This is the legendary battlefield victory of British general Bernard Montgomery over the Desert Fox, German field marshal Erwin Rommel—what Churchill famously called, after suffering through three disastrous years of German victories, “the end of the beginning.”

As recent scholarship shows, the Germans had designs on Egypt and the Levant that went beyond the purely strategic objectives of controlling the Suez Canal, the eastern Mediterranean and the oil fields of Arabia. In fact, there is convincing evidence that the Nazis planned to follow on Rommel’s expected sweep into Cairo and then onto Jerusalem with the extermination of the Jewish communities of Egypt, Palestine and beyond. If the Panzers were not defeated in the Western Desert, this would likely have added more than 600,000 additional Jews to the Holocaust death toll.

This would have aborted any hope of the Zionist dream for a “Jewish national home” in the historic homeland of the Jewish people. The near annihilation of the Jews of Europe fed the desire for Jewish sovereignty; the annihilation of the Jews of the Levant would have killed it. Israel would never have been.

Torch, Tunisia, El Alamein—to understand how the Middle East we know today came to be and to appreciate the origin and evolution of American policy in a region that has loomed so large in our national consciousness in recent decades, let’s pause to remember the events of the second week of November 1942.

Robert Satloff is executive director of The Washington Institute and author of Among the Righteous: Lost Stories from the Holocaust’s Long Reach into Arab Lands. This article was originally published on the History News Network website.