The controversial Hariri trial will unfold amid growing sectarian violence in Lebanon, the seemingly interminable war in Syria, and a longstanding political stalemate regarding Hezbollah's role in government.

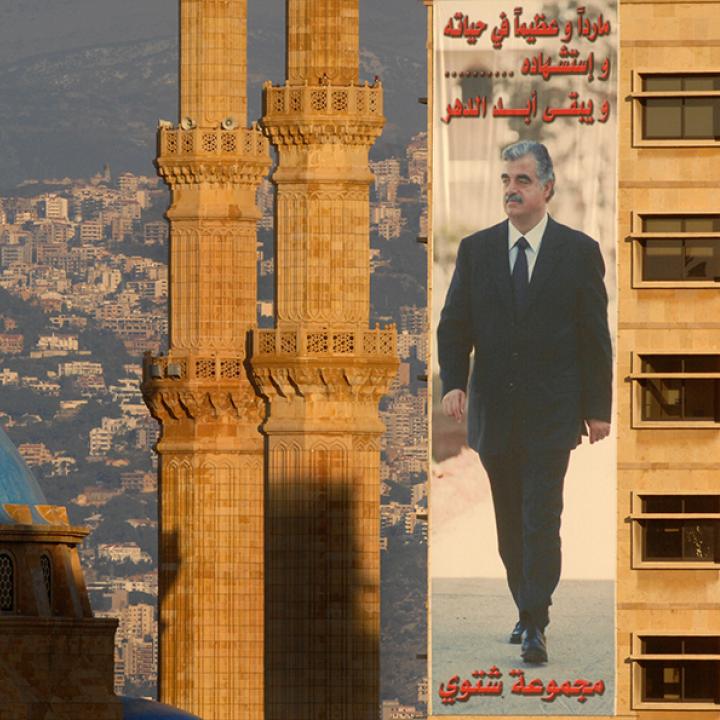

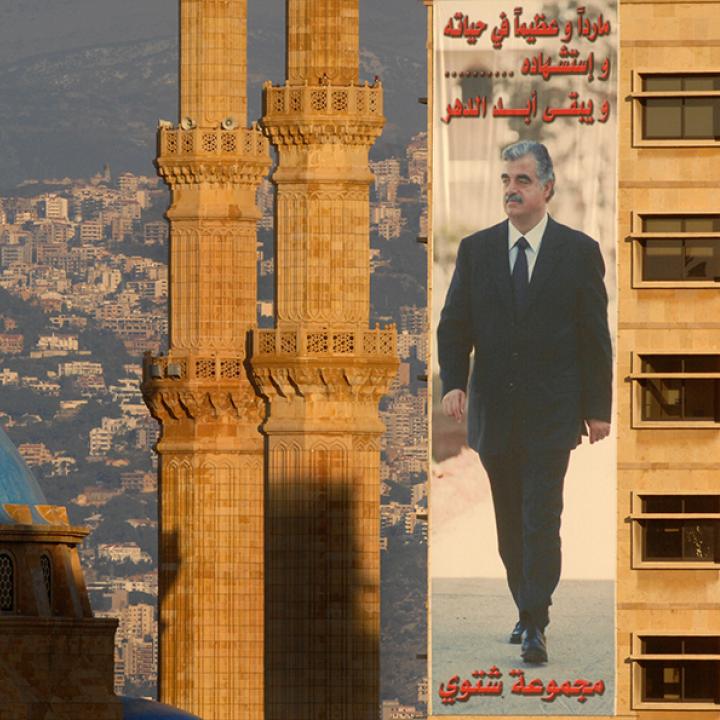

Last week, the four suspects charged with the 2005 murder of former Lebanese prime minister Rafiq Hariri finally went on trial in The Hague. In the coming months, these men -- all members of the Iranian-backed Shiite militia Hezbollah -- will be prosecuted in absentia for their role in the bombing that killed twenty-four people, including Hariri, the leader of Lebanon's Sunni Muslim community. The court proceedings for this overtly sectarian crime are already reverberating in Lebanon, heightening tensions in a state reeling from the Sunni-Shiite war next door in Syria. Further complicating matters, the trial coincides with contentious negotiations in Beirut over the formation of a new government.

BACKGROUND

From 1975 to 1990, Lebanon fought a brutal civil war that killed more than 100,000 people. Ultimately, Saudi Arabia mediated the war's end via a renegotiated political understanding called the Taif Accord, an agreement buttressed by the Syrian occupation of Lebanon. This postwar modus vivendi continued until 2004, when Syrian president Bashar al-Assad sought -- in violation of the Lebanese constitution -- to extend the term of his preferred Lebanese president, Emile Lahoud. Prime Minister Hariri opposed the extension but acquiesced in the face of threats from Damascus. He then left the government in October 2004, but not before endorsing UN Security Council Resolution 1559, which called for all foreign forces -- including Syria's -- to depart Lebanon. On February 14, 2005, he was killed by a massive car bomb in Beirut.

Hariri's murder touched off the Cedar Revolution, which led to the withdrawal of Syrian troops but also repolarized Lebanese society into two camps: the anti-Syrian "March 14" coalition headed by Hariri's son Saad, and the pro-Syrian/Iranian "March 8" coalition led by Hezbollah. Following its victory in the 2005 parliamentary elections, March 14 began to raise the sensitive topic of disarming Hezbollah, kicking off a three-year campaign of assassinations against politicians, journalists, and security officials allegedly perpetrated by Syria and its Lebanese allies. In 2007, the UN Security Council established the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) to prosecute those responsible for Hariri's killing and subsequent political murders.

UPTICK IN VIOLENCE

While the tempo of assassinations in Lebanon abated slightly after 2008, violence resumed with a vengeance after Syrians rose up against Assad's Alawite-Shiite regime in 2011. Over the past two years, as Hezbollah increasingly acknowledged its role as a combatant in Syria, intercommunal violence has proliferated throughout Lebanon. In addition to now-routine sectarian battles between Sunnis and Alawites in Tripoli and border ambushes against Sunni and Shiite jihadists travelling to Syria, Lebanese Sunni militants have clashed with Hezbollah troops in Sidon. Sunni militants have also begun directly targeting local Shiites and Hezbollah strongholds, car-bombing Dahiya four times -- most recently on January 21 -- and even attacking the Iranian embassy in Beirut.

Hezbollah has apparently responded by attacking Sunni targets in Tripoli and resuming assassinations of leading Sunni political and security officials, including Hariri confidant Mohamad Chatah on December 27. The presence of an estimated 1 million mostly Sunni refugees from Syria has only exacerbated sectarian resentment.

DELAYED CABINET FORMATION

In March 2013, these tensions prompted Lebanese prime minister Najib Mikati -- affiliated with neither March 8 nor March 14 -- to resign his post. A month later, he was replaced by sixty-eight-year-old Tammam Salam, another unaligned politician. Since then, Salam has presided over a caretaker government prohibited by law from making decisions of consequence. Not surprisingly, the government has accomplished little even by Lebanese standards. To be sure, it is not unusual for Beirut to be without a working government for long periods of time: in 1969, for example, Prime Minister Rashid Karami took nine months to form a cabinet. Yet with presidential elections approaching this May -- the nomination process for which occurs in parliament -- the need to form a government has become more urgent.

Cabinet formation has long been a prickly topic in Lebanon, but the current iteration has been particularly challenging. March 14 is divided on the matter of participating in a government with Hezbollah. As in 2009, Saad Hariri, leader of the Future Movement, has indicated he is amenable to a "national unity" government, but his leading Christian coalition ally, Samir Geagea of the Lebanese Forces party, opposes governing alongside the Shiite militia. "A government of contradictions," Geagea said on January 13, "cannot result in anything."

Seat allocation has also been controversial, though the blocs seem to be moving closer to accepting an even 8-8-8 split between March 14, March 8, and the seats chosen by President Michel Suleiman. Likewise, March 14 has supported the appointment of a "technocratic" or nonpartisan government, though March 8 rejected this proposal.

While these disagreements are not trivial, they may be surmountable. Going forward, the most difficult point of contention will be the bayan wizari (ministerial statement), the main source of policy guidance for the new government. Hezbollah wants the document to incorporate a reference to the group's perennial defense doctrine, joining the "Army, the people, and the Resistance (i.e., Hezbollah)" into a national strategy and -- not coincidentally -- legitimizing the large stockpile of weapons the militia has long employed against Israel. On January 17, Hezbollah cleric Muhammad Yazbeck reaffirmed his organization's support for this formulation during a celebration of the Prophet Muhammad's birthday.

In 2005 and 2009, March 14 agreed to integrate a similar expression into the bayan, but it will be more difficult to do so now, especially in the shadow of the STL. When Chatah was assassinated last month, Hariri issued a statement blaming Hezbollah for the crime and condemning the "proliferation of arms and armed groups at the expense of the state and its institutions." Against this backdrop, a March 14 move toward Hezbollah would not go over well with Hariri's Sunni base.

March 14 has also indicated that in order to participate in a government with Hezbollah, it would need a bayan that reiterates support for the Taif Accord, adheres to the 2012 Baabda Declaration pledging Lebanese noninvolvement in the Syrian war, and sets a timetable for the withdrawal of Hezbollah forces from Syria. Although Hezbollah and March 8 have already accepted -- if not fulfilled -- the precepts of Taif and Baabda, pulling fighters from Syria is a red line that Hezbollah will not readily cross. In any event, as one anonymous March 8 parliamentary deputy told Lebanese daily al-Akhbar on January 14, the bayan is the purview of Shiite speaker of parliament Nabih Berri and cannot be discussed "until the decree to form the government is issued."

PROSPECTS

This week's attack in Dahiya, last week's suicide bombing against Hezbollah operatives in Hermel, and Syrian shelling that killed several Sunni villagers in the border town of Arsal on January 17 have all heightened concerns about further deterioration in Lebanon's security situation. Amid this spike in violence, Hariri may attempt to convince his coalition partners to make concessions and join a government with Hezbollah, as he did in 2009. Alternatively, he might try to exploit impending presidential elections by convincing Free Patriotic Movement leader Michel Aoun, Hezbollah's Christian coalition partner, to run. Aoun, age eighty, has long coveted the presidency and may be responsive to such overtures even if Hariri's intention is to co-opt him and undermine Hezbollah.

Regardless of what deals are struck behind closed doors, however, even a national unity government may not be able to reverse Lebanon's downward trajectory. Although Hariri and Geagea might have enough influence to keep their constituents in check, Sunni jihadists exhibit no loyalty toward March 14 and seem dedicated to extracting revenge against their Shiite enemies in Lebanon, who have aided and abetted the killing of tens of thousands of Sunnis in Syria. At the same time, Hezbollah has demonstrated little restraint when it comes to retaliating against its Sunni countrymen.

In April 2007, Assad warned UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon that the STL "could unleash a conflict which would degenerate into civil war and provoke divisions between Sunnis and Shiites from the Mediterranean to the Caspian Sea." Although the tribunal did not spark the violent spillover from Syria's interminable war, the current trial promises to exacerbate Lebanon's increasingly dangerous sectarian strife. Justice and accountability for Rafiq Hariri's murder was necessary, overdue, and inevitable. Regrettably, it will also come with a high price.

David Schenker is the Aufzien Fellow and director of the Program on Arab Politics at The Washington Institute.