- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

Trump's Plan to Arm Kurds Lays Bare the Strategic Vacuum in Syria

The administration's plan to retake Raqqa from the Islamic State could further inflame tensions with Turkey and Iran.

President Donald Trump has his work cut out for him next week in his first meeting with Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. While many issues crowd their agenda, the situation in northern Syria will be the most difficult. Tensions remain high between the United States and Turkey about the role of the Syrian Kurdish PYD and its military wing YPG in the fight against the Islamic State, following a Turkish air attack on YPG bases along the Iraqi-Syrian border on April 23. In private and publicly, at an Atlantic Council meeting on April 28, Erdogan stressed that he is ready to act further against the PYD.

But, as Foreign Policy reported on May 5 and confirmed by the Trump administration on May 9, the United States plans to move against the Islamic State in Raqqa using -- and arming -- the PYD. Tactically, the United States, whose troops were close to the airstrikes, and which sees no immediate military alternative to the PYD, is in the right. But less so strategically, as the administration appears uncertain or ill-informed about the larger issues at stake in Syria. This tension, if not resolved between the two presidents, could provoke a confrontation between Ankara and Washington in the geostrategic great game looming in the region.

This game in and around Syria isn't the one the United States is now fighting single-mindedly against the Islamic State in its last strongholds in Mosul, Iraq, and Raqqa, Syria; rather, it's the larger carving up of the Levant following the Islamic State's inevitable demise. The Turkish airstrike and a recent Israeli attack on Hezbollah depots at the Damascus airport are chess moves in the larger game: efforts by the Turks, Israelis, Iraqi Kurds, the region's Sunni Arab majority, and (they all hope) the United States to push back against an Iranian- and Russian-led upheaval of the regional order. This is exactly what Trump will hear from regional leaders in Israel and Saudi Arabia in two weeks.

The PYD, from Turkey's standpoint, is part of this upheaval. The strategic difficulty for Washington is that it's not sure, beyond general hostility, what its policy toward Iran and its Hezbollah and Syrian vassals should be -- nor its relationship with the PYD -- once the Islamic State is defeated.

For Erdogan and the Turkish military, the PYD, as a geographical extension of its parent organization, the Turkish-Kurdish insurgent PKK, threatens Turkish territorial integrity at two levels. Ankara and the PKK have been at war in Turkey's southeast for more than 30 years. The PKK claims to represent Turkey's roughly 15 million Kurds, almost one-fifth of the population. Ankara cannot militarily defeat the PKK, but it has effectively blocked it from uniting the Kurdish population, now divided into several basic camps: a pro-PKK element; religious Kurds in the southeast who often vote for Erdogan's AKP party; and a large minority assimilated by language, family, and geography with ethnic Turks. The result is a bloody stalemate broken by temporary cease-fires without any real resolution, as the PKK's Marxist core -- loyal to imprisoned leader Abdullah Ocalan -- seeks ultimately a Kurdish state carved out of much of Turkey.

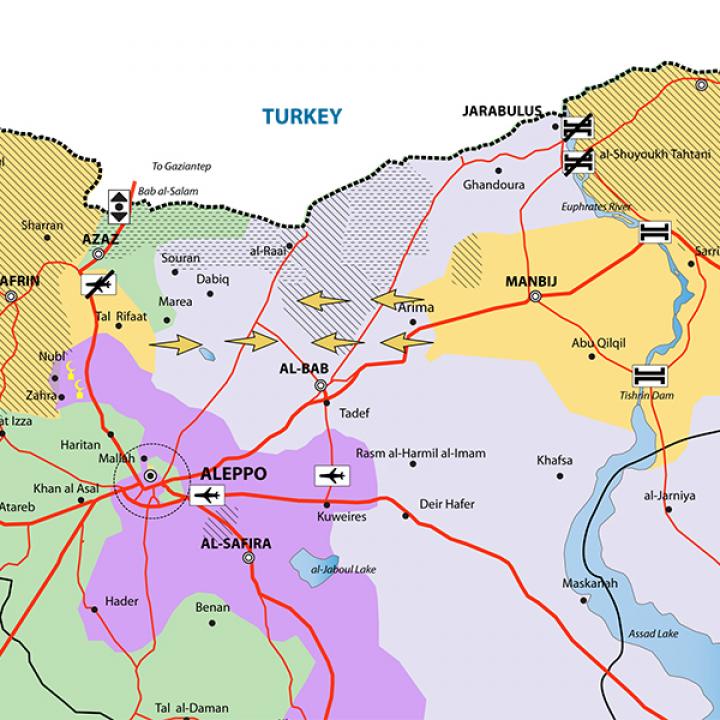

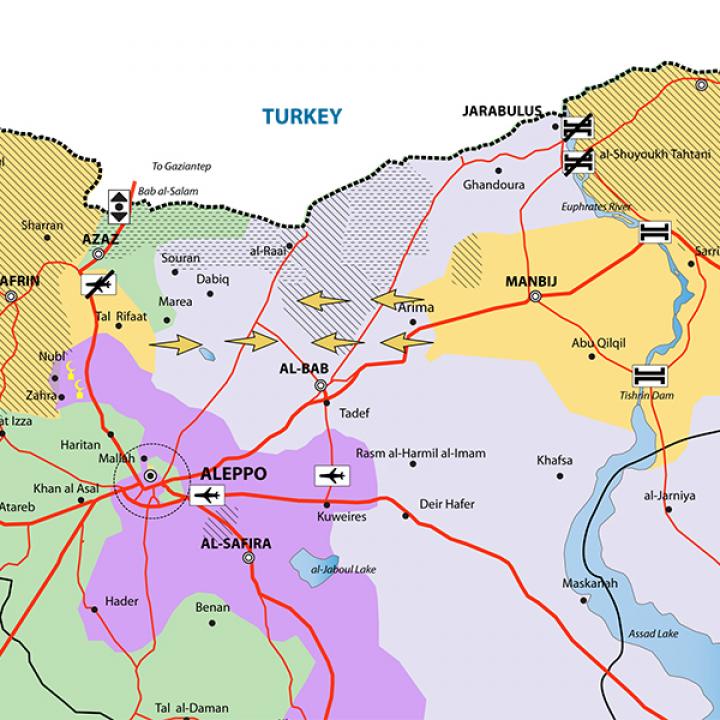

Thus, Erdogan's great worry about the United States arming the Kurds in Syria. Were the PYD to form a contiguous state along Turkey's southern border it would dramatically increase the PKK's reach, forcing Turkey to deal simultaneously with the PKK insurgency inside the country and a PKK-allied state to its south. Even if an uneasy truce with the PYD endures, Turkey's strategic situation would worsen, and push many Turkish Kurds to choose sides. Ankara has long warned what it sees as a naive Washington not to support the PYD against the Islamic State, which it fears would facilitate a PYD-dominated northern Syria after the Islamic State is defeated. Turkey's alternative against the Islamic State, a Turkish-trained Syrian Sunni force, is not favored by the Pentagon, however.

Even worse, the PYD, with close trade ties with the Syrian regime, could form common cause with Bashar al-Assad, the Iranians, and Russia to surround Turkey, opening an Iranian ground corridor through northern Iraq and PYD territory to Damascus. These concerns motivated the Turkish intervention in Syria last August, as much to push back against the Islamic State as to block a contiguous Kurdish zone. The April strikes against PYD/PKK targets in northeastern Syria and in Sinjar, Iraq -- along the aforementioned corridor, where PKK forces are arrayed against Turkey's Iraqi Kurdish ally Masoud Barzani -- again confirmed this willingness to use force to advance Turkish territorial concerns.

Washington appears in turn clueless and furious at Erdogan, particularly with the latest bombing. (Erdogan's bombast, authoritarianism, and dismissal of U.S. concerns generate strong reactions, especially after Trump congratulated him on his controversial referendum win and invited him to Washington.) Washington needs the PYD and its Arab allies to lead the attack on the Islamic State capital of Raqqa: in part because the United States will not commit ground troops itself, in part because the PYD fighters are among the region's best. Tactically, to eliminate the more immediate if less strategic threat -- the Islamic State -- a temporary alliance with the PYD makes sense. But the U.S. military further infuriates Turkey by asserting frequently that the PYD can be differentiated from the PKK (despite former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter's Senate testimony last April, and a detailed report from May 4 by the International Crisis Group documenting the PKK's domination of the PYD and the Syrian Democratic Forces, an umbrella rebel group). This feeds Turkish suspicion that, strategically, the United States plans to use the PYD against Turkey -- a long-standing if unsubstantiated Turkish concern.

But the Trump administration as a whole strengthens this concern by ignoring the stakes in the region beyond defeating the Islamic State. All of America's regional allies feel themselves under threat from Iran, while Turkey sees a second threat from Iran's possible ally, the PKK/PYD.

While the Trump administration -- in contrast to President Barack Obama -- recognizes in principle Tehran's threat to regional order, it clearly has not worked out a strategy to contain it. Such strategizing is hard, and particularly for the United States. In contrast, the military campaign against the Islamic State, fulfilling a Trump campaign pledge, is a "good war" with low casualties, high public support, and victory in sight. For good reason, it is the unchallenged priority. But the Islamic State cannot upend Middle East order. Iran and its friends can. So, as is often the case, Washington is focusing on tactical feel-good wins while ignoring the messy day-after politics and thus risking long-term losses. Now, Trump faces a possible confrontation with NATO ally Turkey -- economically and militarily the strongest state in the region, and irreplaceable in any strategy to contain Iran.

Erdogan's visit offers a chance to defuse this pending crisis. Nothing is certain with the increasingly unpredictable Turkish president. But if Trump convinces him that he has a regional containment strategy against what Erdogan recently called "Persian expansionism"; that his administration's collaboration with the PYD is limited by time, mission, and quality; and that Turkey will have a role in liberating Raqqa -- as the local tribes desire -- then a crisis with Ankara might be avoided, and a common effort against the greater regional threat initiated.

James F. Jeffrey is the Philip Solondz Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute and former U.S. ambassador to Turkey and Iraq.

Foreign Policy