- Policy Analysis

- Policy Alert

Turkey’s Energy Confrontation with Cyprus

While much of the world is focused on the Strait of Hormuz, tensions are also mounting rapidly in the East Mediterranean.

The hydrocarbon riches of the Nile and Levant geological basins have already transformed the Egyptian economy and expanded Israel’s energy options, but the possibility of similar good fortune for Cyprus is being undermined by a dangerous Turkish power game. Apparently unable to find oil or natural gas in its own Mediterranean waters, Ankara has claimed rights in areas that the international community regards as part of Cyprus’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Israel and Egypt may be drawn into the growing diplomatic row, and a military clash with Turkey is possible.

According to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, a country’s territorial waters stretch 12 nautical miles out to sea, but its EEZ can extend an additional 200 miles, where it can claim fishing, mining, and drilling rights. When the maritime distance between two countries is less than 424 miles, they must determine an agreed dividing line between their EEZs.

Yet Turkey has not signed up to the convention because the document grants significant rights to island territories. Ankara instead claims rights based on its continental shelf, a perspective that severely limits Cypriot rights. These rival claims, complicated by the island’s continued division into Greek and Turkish Cypriot entities, are well illustrated in the State Department map “Selected Energy Infrastructure in the Eastern Mediterranean.” Aside from Ankara, the rest of the world recognizes Cyprus as one country, with the government in Nicosia having sovereignty if not control over all its territory.

Such recognition infuriates Turkey, which has steadily increased its assertiveness inside the island’s EEZ. So far this year, it has:

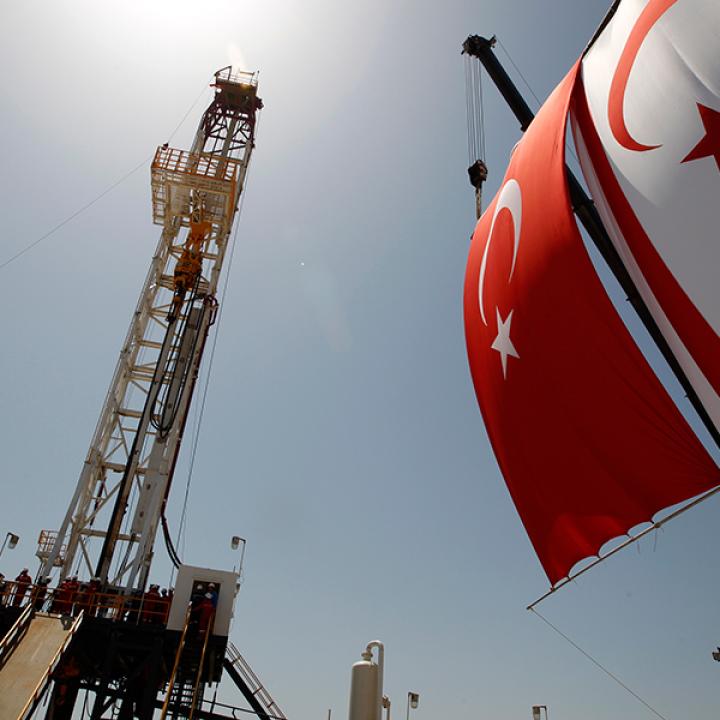

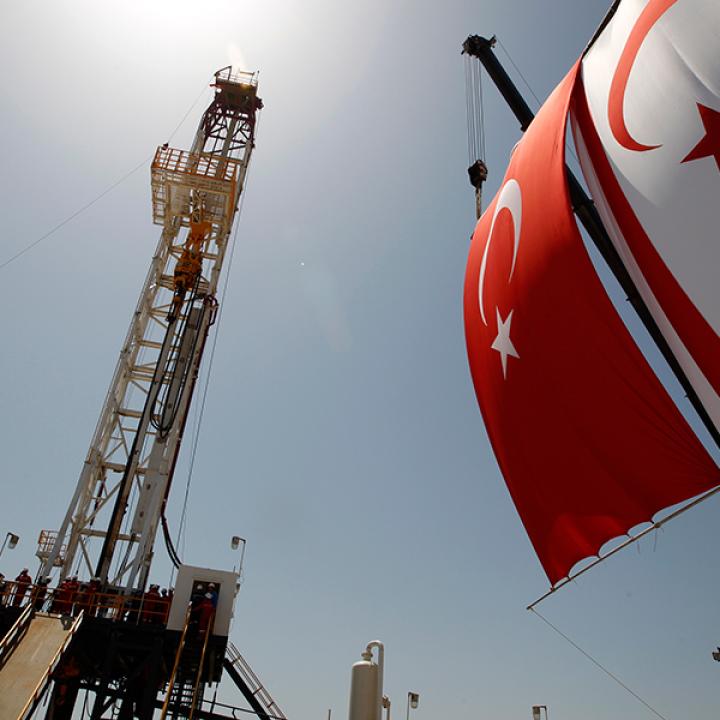

- Sent a drillship to operate fifty-five miles west of Cyprus, well inside Nicosia’s claimed EEZ. Ankara bought the ship in 2017, repainted it to look like the Turkish national flag, and renamed it Fatih after the fifteenth-century Ottoman conqueror of Istanbul.

- Assigned a seismic survey ship to explore in an area directly south of Cyprus, where Nicosia had already given a license to Italian oil giant ENI. The ship was brightly repainted like the Fatih and named after the Ottoman admiral Barbaros Hayreddin Pasa.

- Ordered the identically liveried drillship Yavuz (meaning “inflexible” or “resolute”) to work in an area off the Karpas Peninsula, a part of the island that Ankara unilaterally designated as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus after invading in 1974 to counter a pro-Greek coup attempt in Nicosia.

Alongside such moves, the Turkish military has been harassing Cypriot oil and gas exploration efforts for years. The worst incident was in March 2018, when Turkish warships forced a vessel contracted by ENI to abandon its drilling attempts in Block 3, which lies east of the island and close to the maritime boundary with Lebanon. Ankara may have been responding to the discovery of the Calypso gas field, announced the previous month by a consortium of ENI and the French company Total in an area southwest of Cyprus. Turkey regards that offshore area as belonging to Egypt, even though Cairo’s own maritime boundary accord with Nicosia puts the field in Block 6 of Cyprus’s EEZ.

The stakes have only increased in 2019:

- In February, Exxon Mobil announced the Glaucus (aka Glafcos) discovery in Nicosia’s Block 10 south of Calypso, establishing a direct American link to the issue.

- Egypt was named the host of the new East Mediterranean Gas Forum, a group that also comprises Cyprus, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority. Turkey and Lebanon are not included.

- The United States has reportedly facilitated maritime boundary negotiations between Israel and Lebanon. If successful, these talks could open the waters off Lebanon’s coast to oil and gas exploration and reduce Beirut’s tensions with Israel.

- Earlier this month, Cairo approved a subsea pipeline between Cyprus’s first gas field, Aphrodite (discovered in 2011 but yet to be exploited), and the Egyptian gas liquefaction and export terminal of Edku, near Alexandria. The consortium that owns the field’s license is led by Houston-based Noble Energy, which also operates Israel’s Tamar and Leviathan gas fields. When Aphrodite was first found, Turkish fighter jets buzzed supply helicopters flying from Israel. Part of the field was later determined to lie in Israel’s EEZ, so if Turkey repeats such tactics while work begins on bringing the field into production, Israel will likely respond forcefully.

- On July 15, EU foreign ministers approved sanctions on Turkey because of its “illegal” exploration activities off the coast of Cyprus, an EU member. Although the sanctions were light, Ankara responded angrily and vowed to continue drilling. On July 22, Turkish foreign minister Mevlut Cavusoglu appeared to back down slightly, noting that the government would not be sending an extra seismic ship to the area as originally planned. Two days later, however, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan declared that “threatening to sanction” Turkey will not stop its drilling activities. “The recent steps we have taken,” he noted, “have clearly demonstrated our sensitivity to protect Turkish Cypriot rights, laws, and benefits.” Meanwhile, the leadership of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus proposed a joint committee with Greek Cypriots to discuss the sharing of oil and gas revenues, but Nicosia rejected the idea.

Washington’s relations with Ankara are already in turmoil following the delivery of Russian S-400 missiles and the decision to suspend Turkey from the F-35 project. Tensions in the East Mediterranean may appear small by comparison, but they cannot be allowed to fester given the potential for dangerous escalation.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy at The Washington Institute.