- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3954

U.S. Election 2024: Views from the Middle East

A panel of distinguished journalists from across the Middle East discuss regional perspectives on the second Trump administration’s potential approach to critical issues of war and peace.

On November 7, The Washington Institute held a virtual Policy Forum with David Horovitz, Barcin Yinanc, and Nadim Koteich, moderated by Robert Satloff. Horovitz is founding editor of the Times of Israel and former editor-in-chief of the Jerusalem Post and Jerusalem Report. Yinanc, an editor at the Turkish news site T24, formerly held senior editorial posts at Hurriyet Daily News and CNN Turk. Koteich is general manager of Sky News Arabia and host of the program Tonight with Nadim. Satloff is the Institute’s Segal Executive Director and Howard P. Berkowitz Chair in U.S. Middle East Policy. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks.

Robert Satloff

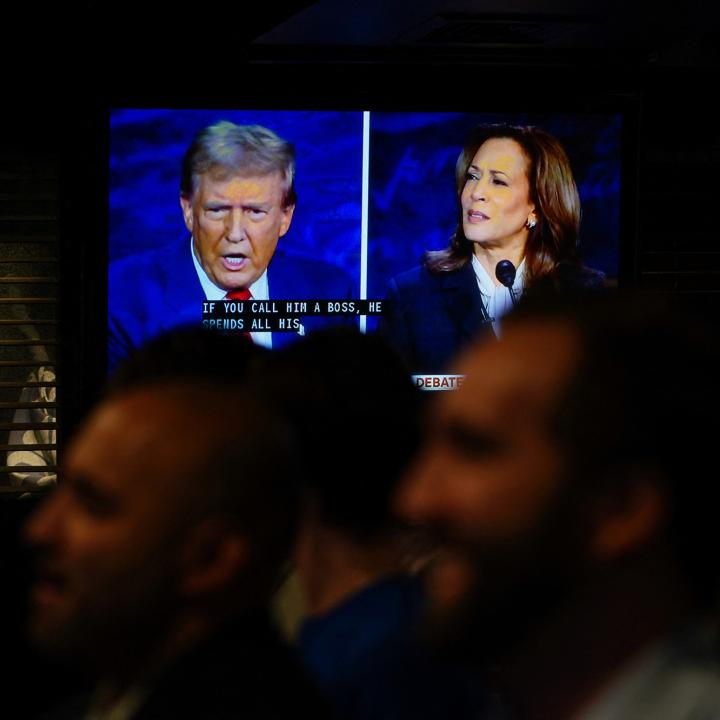

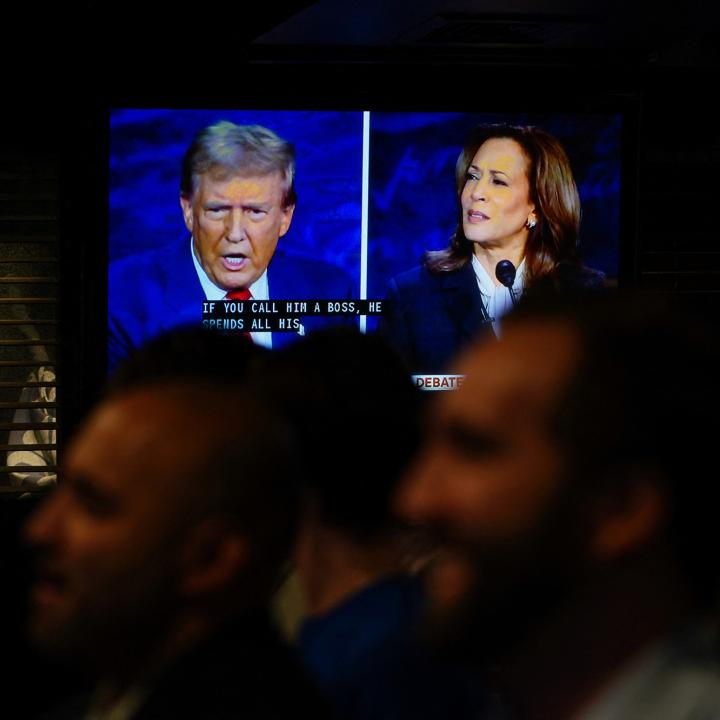

The November 5 election was a clarifying moment in American politics. Many expected a close contest whose outcome would not be known for days, but instead Donald Trump’s victory was decisive and clarifying. He will now become only the second person in history to serve two non-consecutive terms as president of the United States. How are political leaders in the Middle East and their publics reacting to these results?

David Horovitz

Context is essential: when discussing Trump’s election and the formation of a new administration, it is important to remember that Israel is being attacked every day on multiple fronts with rockets, missiles, and drones, often by countries and groups with whom it shares no borders or territorial disputes. Israelis across the political spectrum believe that the world has failed to appreciate their plight and has turned the victim into the aggressor. It is impossible to understand the political situation inside Israel without appreciating this perception.

There are few politicians more popular than Trump among the Israeli people—a fact that underscores the current distance between Israel and the American Jewish community, which voted overwhelmingly (if less so than in the past) for the Democratic candidate. During his first term, Trump advanced numerous policies deemed favorable to Israel, such as moving the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem, recognizing Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal, and brokering the Abraham Accords. These moves were widely appreciated across the Israeli public.

Similarly, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu is delighted by Trump’s victory and views him as a natural ally; the mainstream opposition has welcomed his victory as well. Although most Israelis have warm feelings toward President Biden, this did not extend to Vice President Harris, whom they perceived—rightly or wrongly—as succumbing to the anti-Israel pressure of her party’s progressive wing.

Looking forward, some have questioned whether Netanyahu will try to take advantage of a more sympathetic U.S. administration to advance West Bank settlement expansion and, possibly, annexation. He will certainly feel less constrained about pursuing policies favored by the far-right members of his coalition. Building on Trump’s record of negotiating the Abraham Accords, some also hope that the new administration will facilitate additional normalization agreements, especially with Saudi Arabia. Only time will tell how much tension there is between these two objectives of expanding settlements and broadening normalization.

Regarding regional policy, Trump has stated that he would like Israel to “finish the job” in Gaza and Lebanon, which opens the possibility for diplomatic agreements on both fronts. Many have assumed that Trump will not pressure Israel on the peace process with the Palestinians, but no one should forget that he met with Palestinian Authority president Mahmoud Abbas during his first term and praised him as a potential peacemaker. On Iran, Israelis believe Trump will likely be tougher than the Biden administration—though Trump advisors have specifically ruled out a policy of regime change and emphasized that they want to avoid war in the Middle East.

Barcin Yinanc

Trump’s victory has met with mixed reactions in Turkey, reflecting the polarization between those who support President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and those who oppose him. Trump’s return means that democratic backsliding and authoritarian consolidation in Turkey will likely continue. When a superpower such as the United States is ruled by someone widely viewed as indifferent to the rule of law, other world leaders will follow. Erdogan has experience working with Trump from the first term and will presumably build on this to reach a strategic understanding during the second term.

Among other issues, Ankara will be watching to see if Trump delivers on his pledge to end the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. It will also cautiously watch how he approaches Iran and Israel. On one hand, the weakening of Iranian proxies could be strategically beneficial for Turkey. On the other hand, escalation toward all-out war between Iran and Israel would be devastating for Turkish interests. Ankara also believes that any shrinking of Iran’s influence would benefit Kurdish political aspirations in the region.

Accordingly, Erdogan will likely approach the new administration in its early days to renew his offer of taking responsibility for security in Syria, enabling the United States to withdraw its troops. In his view, American troops are protecting Kurdish forces that are linked to the terrorist Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).

More broadly, Turkey has long felt marginalized under the Biden administration. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has only visited Ankara a handful of times, mainly to discuss Turkey’s veto of Sweden’s NATO membership. If Trump fosters better dialogue with Turkey, Erdogan may be willing to moderate his hostile language toward Israel.

Nadim Koteich

The Gulf Cooperation Council countries have welcomed Trump’s victory, in large part because they favor his transactional approach to foreign policy over what they perceive as President Biden’s idealistic approach. GCC countries want an American leader who understands their region’s unique challenges, and they believe this awareness has been absent under the Biden administration.

The GCC is also balancing relationships with U.S. competitors so that it does not have to rely solely on the United States for strategic cooperation. For example, Saudi Arabia maintains security ties with Washington while simultaneously cultivating economic ties with China, India, and Russia. Indeed, Moscow now wields considerable influence in regional countries as varied as Libya, Syria, and Sudan.

On Iran, GCC nations want Washington to adopt a firm stance against the regime’s regional troublemaking while avoiding direct confrontation. It seems clear that Trump does not want war with Iran, and that Tehran does not want war with Israel. Although regional tensions and conflict will continue, there is greater potential for calm under a second Trump administration. The Iranian regime’s vulnerability is an advantage for Trump, and he may sense an opportunity for negotiations that allow him to put his name on a major diplomatic agreement.

Finally, many Arabs recognize that Israel cannot pursue peace until it feels secure, but the Israeli government seems to be pursuing a policy in Gaza and Lebanon whose civilian cost goes far beyond targeting Hamas and Hezbollah. This makes the eventual pursuit of peace much more difficult. Astonishingly, the Abraham Accords have survived the past year of war, largely through the committed leadership of the United Arab Emirates. But no one should be lulled into thinking that Saudi Arabia or other countries can make their own peace with Israel in the current environment, given how sensitive the Palestinian issue is for their populations.

This summary was prepared by Manuel de la Puerta. The Policy Forum series is made possible through the generosity of the Florence and Robert Kaufman Family.