- Policy Analysis

- Policy Alert

U.S. Officials to Mediate Israel-Lebanon Maritime Border Talks

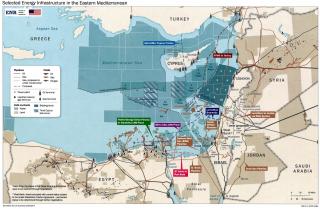

Negotiating a dividing line would enable Beirut to fully exploit potential offshore oil and gas reserves.

After almost a decade of intensive diplomatic efforts, the United States has succeeded in brokering an agreement between Israel and Lebanon to start formal negotiations on demarcating their maritime border. Barring a last-minute change of heart in Beirut, the talks are scheduled to begin in early October after the Jewish high holidays. Under the auspices of a U.S. delegation, representatives will meet in Naqoura at the headquarters of the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). A UN rapporteur will attend the sessions at Lebanon’s insistence, but his notes will not be filed at the UN due to Israel’s objection.

The breakthrough was achieved after Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs David Schenker visited Jerusalem and Beirut earlier this month. To overcome the parties’ persistent differences regarding the legal basis and format of negotiations, the U.S. government issued side letters that provide assurances to both countries. One unresolved issue concerns possible linkage between maritime decisions and final demarcation of their land border, especially relating to the small area that Israel calls Mount Dov, in the vicinity of Shebaa Farms on the slopes of Mount Hermon.

Israeli energy minister Yuval Steinitz was already authorized to signal Lebanon that his government is prepared to split the 860 square kilometers of contested maritime territory in a 58:42 ratio in Beirut’s favor. The Lebanese are eager for the French company Total to start drilling in Block 9 adjacent to the contested area, while Israel is preparing international tenders for drilling at the neighboring “Alon D” block.

The main Lebanese interlocutor for this process has been the Shia Muslim speaker of parliament Nabih Berri, who acted with President Michel Aoun’s consent and, presumably, Hezbollah’s tacit approval. Lebanon’s financial meltdown likely accelerated the State Department’s preparatory efforts. On the other side, Israeli officials believe that once a demarcation line is approved and Lebanon starts exploring for natural gas, the risk to Israeli offshore gas rigs will be greatly diminished.

While Egypt and Jordan have been cooperating with Israel on gas projects for some time, dealing with Lebanon has been problematic. The maritime border challenges are both legal and geological. The usual first requirement is establishing an agreed land border in order to pin down where it meets the sea. But in this case the relevant border point—Rosh Hanikra/Ras Naqoura—is still technically disputed and terminates in a towering white cliff with no beach.

Moreover, while nearby Cyprus has an agreed maritime border with Israel, its attempts to reach one with Lebanon were stymied by Turkish pressure on Beirut. In response, an irritated Nicosia decided to draw its line with Israel from the southern end of the line it had hoped to draw with Lebanon. From Beirut’s perspective, the so-called “tri-point” where the three countries’ exclusive economic zones meet is further south. This contested pizza slice of territory will therefore be discussed in the upcoming talks.

Israel has not yet drilled in the contested area, but nearby discoveries to the south have fed optimism that hydrocarbon deposits could exist in commercial quantities deep below the seabed. Although such deposits may wind up straddling any maritime border reached in the coming weeks, this complication arises in many places around the world, and legal templates exist for shared exploitation.

Considering the country’s dire financial situation, the talks are good news for Lebanon because an agreed boundary could benefit the economy in the long term. Yet these benefits may be negated if Hezbollah is permitted to maintain its current access to most of Lebanon’s key ministries, since the group and its allies would no doubt tap any oil and gas profits that materialize. On the one hand, then, it is important to shelter the maritime demarcation deal from U.S. pressure related to Lebanon’s political reform process. On the other hand, Washington needs to understand that only the corrupt political class will benefit from the deal unless serious changes are made in Lebanon’s political structure—which means supporting early elections and a new electoral law, as well as implementing the reforms stipulated during the Paris meeting last December and more recently.

Hezbollah has always been good at buying time when it is cornered. As sanctions pile up against the group, its domestic allies, and Iran, some observers in Lebanon are concerned that maritime talks may just be the latest bid to stall any real reforms and freeze further outside pressure. Washington should therefore continue its efforts to designate members of the corrupt political class and show the Lebanese people that this deal is for their benefit, not that of the Hezbollah axis.

Finally, it is important to note that the drive toward a potential maritime agreement is not part of the recent normalization process seen between Israel and other Arab states. From the perspective of Hezbollah and the current Lebanese government, maritime demarcation would not reflect any change in their attitudes toward Israel or the Blue Line land border drawn by the UN following the 2006 war. Yet it may remove at least one danger: that any future confrontation with Hezbollah will necessarily spill into Israel’s offshore gas fields.

Ehud Yaari is a Lafer International Fellow with The Washington Institute and a veteran commentator for Israeli television. Simon Henderson is the Institute’s Baker Fellow and director of its Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy. Hanin Ghaddar is the Friedmann Fellow in the Institute’s Geduld Program on Arab Politics.