Sustaining U.S. and Turkish assistance to the Syrian Kurds is crucial to blocking ISIS and stemming Russian influence, as is resolving Ankara's Kurdish problems at home, but sending heavy weapons to the PYD would likely have unintended consequences.

The U.S. government continues to debate whether it should provide the People's Defense Units (YPG) -- the military wing of the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) -- with heavy weapons, including antitank and antiaircraft missile launchers. The YPG has helped capture territory from ISIS in recent months, with U.S. backing that has included airstrikes and ammunition. But the situation is more complex than simply increasing assistance to an allied group.

Although heavy weapons could enable the YPG to seize more territory from ISIS, any such progress might quickly be rolled back -- that is, helping the group escalate the war in the north could spur Arab nationalist backlash against Kurdish territorial advances, perhaps boosting support for ISIS. And if U.S. weapons end up in the hands of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), the PYD's parent organization in Turkey, it could seriously strain U.S.-Turkish military ties. At the same time, however, abandoning the PYD could deliver the Syrian Kurds into Russia's hands, against Washington and Ankara's interests. Accordingly, while Washington should weigh against providing heavy weapons to the PYD, Turkey needs to build good ties with the group and make peace with the PKK.

THE PYD IS NOT PART OF THE ANTI-ASSAD OPPOSITION

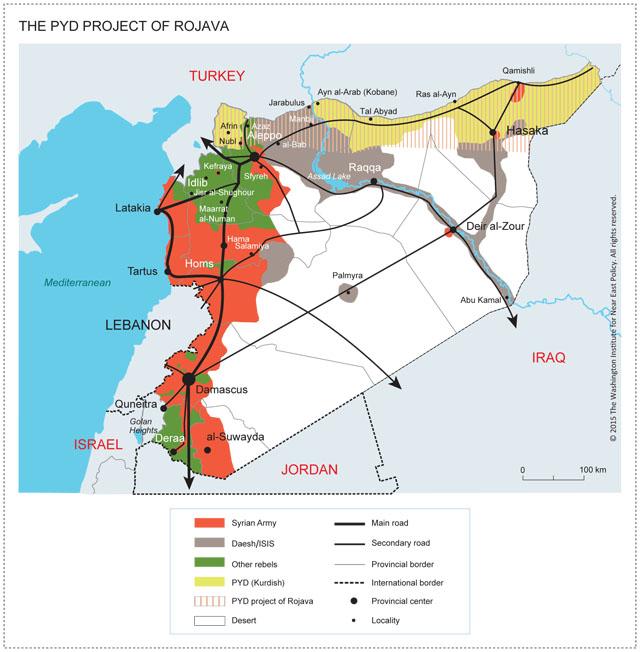

The Syrian war remains a nonbinary conflict defined by a chaotic web of shifting alliances, as seen in the relative lack of military confrontation between ISIS and the Assad regime. The PYD and the regime have similarly avoided major clashes, instead choosing an informal nonaggression pact. In July 2012, the regime evacuated most Kurdish-majority areas in northern Syria, and the newly formed YPG -- an alliance of the PYD and the Kurdistan National Council (KNC) -- took control there, establishing three self-declared cantons of Rojava or "Western Kurdistan." These include Afrin in the northwest, separated from the conjoined cantons of Kobane and Jazira in the north and northeast, all along the Turkish border.

Since then, the PYD has not operated against Assad; in fact, it has tolerated sizable contingents of regime forces in Kurdish territories near Qamishli and Hasaka, where the army controls the airport, a border crossing, and several government buildings. The PYD's nominal goal is to achieve territorial autonomy and defend Kurdish areas in Syria against ISIS. But the group has a more ambitious agenda: after its forces repelled an ISIS attack with U.S. and coalition assistance earlier this year, the PYD launched an offensive to unite the Kurdish border cantons in the name of cutting off ISIS smuggling routes into Turkey. During the first campaign launched in June, the group took over the mixed Kurdish-Turkmen-Arab area of Tal Abyad. As a possible harbinger of ethnic cleansing to come, a recent Amnesty International report accused YPG forces involved in the operation of evicting Arabs and Turkmens from their homes and destroying their property. The PYD is now trying to convince Washington to allow it to move westward across the Euphrates River and seize a mixed area of Turkmens, Arabs, and Kurds, with the goal of uniting Kobane and Jazira with the Afrin canton. This would form a contiguous Kurdish belt along the border -- a clear redline for Ankara.

Supporting the PYD as a solution to the ISIS problem has two limitations: (1) the YPG's limited military and political range outside Kurdish population centers, and (2) Ankara's perception that the PYD is a front for the PKK, the U.S.-designated terrorist group that has waged war on the Turkish government for decades. With an eye toward these constraints, Washington recently announced that it would arm and support a new umbrella organization called the Democratic Forces of Syria (DFS), which includes the YPG and the Syrian Arab Coalition -- an alliance of several rebel factions including Jaish al-Thuwar and Jaish al-Sanadid, as well as Assyrian Christians. U.S. backing for this nascent coalition of some 5,000 fighters is aimed at pressuring the ISIS stronghold at al-Shadadi south of Hasaka, thus cutting the links between the so-called Islamic State's "capital" of Raqqa and its Iraqi stronghold in Mosul. Washington plans to support this effort with airstrikes and air-dropped weapons supplies. In exchange for Turkey's support of the operation, U.S. officials have reportedly agreed -- for now -- to abide by Ankara's redline that no Kurdish forces can cross west of the Euphrates.

Perhaps most important, the 100 pallets of arms recently delivered to the YPG and DFS included no heavy weapons. As described above, any such transfer could backfire because of the PYD's ambiguous (at best) relationship with the Assad regime. Apart from fighting ISIS, the group could just as well use heavy weapons to carve out more territory and spin the Kurdish regions out of Syria, thereby escalating the war and setting in motion de facto partition.

THREAT TO U.S.-TURKISH MILITARY TIES

The PKK established the PYD in 2003, and since then, the Syrian group has been deferential to the leadership and ideology of its Turkish parent. Turkey therefore considers the PYD to be a terrorist movement like the PKK. Ankara's peace talks with the latter collapsed in July, leading to a wave of violence inside Turkey. Although the PKK declared a unilateral ceasefire on October 10, eleven Turkish security officers have since been killed in attacks.

Given the close relationship between the two groups, at least a portion of any U.S. heavy weapons provided to the PYD would inevitably end up with the PKK, potentially enabling it to conduct a symbolic strike such as downing a Turkish fighter jet -- a disturbing development that would effectively paralyze U.S.-Turkish military ties for years to come. Although bilateral relations have been testy of late, Turkey's participation in the anti-ISIS coalition serves Washington's interests, and Ankara remains a NATO ally. Following a decade of disagreements, a golden opportunity to strengthen U.S.-Turkish military ties recently emerged in the form of Russia's intervention in northern Syria. Moscow has long been Turkey's most feared enemy, with the Ottomans fighting nearly twenty brutal wars against Russia. By annexing Crimea and sending troops to Syria, Moscow has become Turkey's uncomfortably close neighbor to the north and south, causing great concern in Ankara and giving Washington an opening to rejuvenate the military relationship.

ANKARA CANNOT IGNORE THE KURDS

In a recent interview, PYD leader Salih Muslim welcomed the Russian deployment, and Moscow has reportedly encouraged the YPG to unite the Kobane and Afrin cantons (see PolicyWatch 2499, "Syria's Kurds Are Contemplating an Aleppo Alliance with Assad and Russia"). This should be a warning sign for Turkey -- if the PYD, and by extension the PKK, were to become Russia's client, Ankara's hopes of negotiating with Turkish Kurds to resolve their problems would effectively end. Russian backing for the PYD/PKK would make these groups what Hezbollah is for Israel: an armed proxy fighting someone else's war against a U.S. ally.

Accordingly, Turkey has to pull the carpet out from under Moscow by building better ties with the PYD. In the short term, this means supporting the DFS with light weapons backed by U.S. airpower. But the best way to undermine Russia would be through Turkish-Kurdish peace at home. Washington should encourage Ankara to find a lasting means of ending the fight with the PKK through a political solution, which would help keep the Kurds in both Turkey and Syria on Ankara and Washington's side.

Soner Cagaptay is the Beyer Family Fellow and director of the Turkish Research Program at The Washington Institute, and author of The Rise of Turkey: The Twenty-First Century's First Muslim Power, named by the Foreign Policy Association as one of the ten most important books of 2014. Andrew Tabler, the Martin J. Gross Fellow in the Institute's Program on Arab Politics, is the author of "Syria's Collapse and How Washington Can Stop It" (Foreign Affairs) and the book In the Lion's Den: An Eyewitness Account of Washington's Battle with Syria.