Young Islamists are using Facebook to organize violent opposition.

After Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi's ouster last summer, analysts warned that a disempowered Muslim Brotherhood might embrace jihad. Toppling an elected Islamist government, some argued, would lead the Brotherhood to abandon the democratic procedures that it accepted only belatedly, and advance its theocratic vision through al-Qaeda-like terrorism instead. Nearly eight months later, however, these expectations haven't materialized. While Sinai-based militants have killed over 300 military and police officers since July, there is little evidence that many, if any, Muslim Brothers have joined the jihadis' ranks.

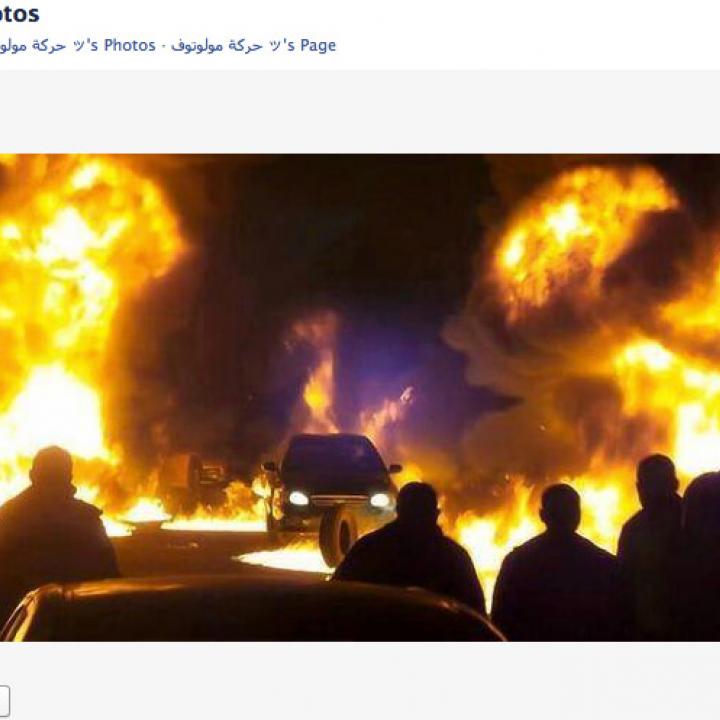

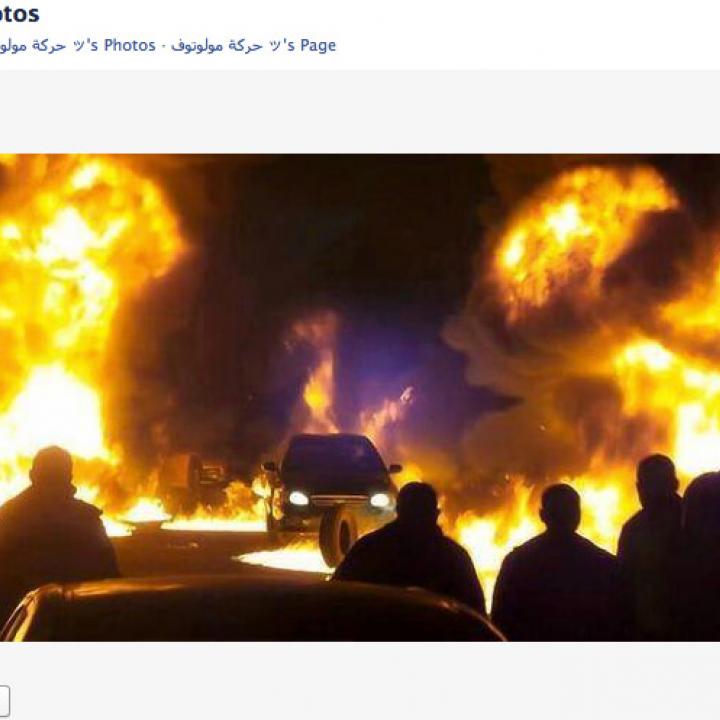

Yet amidst a crackdown that has killed over 1,000 Morsi supporters, Muslim Brothers aren't turning the other cheek. Armed with improvised weapons such as flaming aerosol cans and Molotov cocktails, they are directing a campaign of lower-profile violence against various governmental and civilian targets, aiming to stir chaos and thereby weaken the post-Morsi regime. Ironically, they are embracing the same tactics that anti-Brotherhood activists used to undermine Morsi's authority after his November 2012 power grab.

To promote these violent efforts, Muslim Brothers appeal to their supporters through social media, establishing violent Facebook groups that have attracted thousands of "likes." For example, the "Execution Movement" Facebook page, which was founded in early September to call for the deaths of Egypt's top security officials, urges its roughly 3,000 followers to burn police cars. "There are 34,750 police officers in Egypt...80% of them have cars," reads a January 26 post that spread across pro-Brotherhood Facebook pages. "If we exploit the current situation of chaos and, during the night…burned 1000 [police] vehicles...Either the government will compensate [the officers] with new cars, which will cause imbalance in the budget and popular anger...or leave them without cars like the rest of the population, and this of course will have a big impact on their morale and their performance." Indeed, police vehicles appear to be these groups' most frequent targets.

One of the most prominent violent pro-Brotherhood Facebook groups is the "Molotov Movement," which emerged in late 2013. Beyond posting photos of attacks, it provides instructions for mixing Molotov cocktails, constructing Molotov cocktail launchers, and using fire extinguishers as weapons. Its popularity exploded in late January, when it took credit for a series of arson incidents, and it reportedly had over 70,000 followers by the time Facebook shut it down for promoting "vandalism" in mid-February. The "Molotov Movement" quickly resurrected itself, however, creating numerous regionally-oriented Facebook pages that claimed responsibility for burning a checkpoint in October 6 City on February 18, an Alexandria police station on February 19, and three vehicles belonging to a Giza police major on February 21, among other incidents.

Despite their best efforts, Facebook and the Egyptian government struggle to contain these violent groups, because Muslim Brothers can always establish new Facebook pages and publicize them through other pro-Brotherhood pages. This is precisely what happened after the February 24 arrest of eight alleged "Molotov Movement" activists: As the group's activity slowed considerably, violent Brotherhood content simply migrated to other pro-Brotherhood pages, such as "Islamic Egypt" (554,000 "likes") and "Movement 18" (58,000 "likes"), which touted attacks on police cars, television station vehicles, roads, and even the engagement party of a military general's son. These pages also encourage their members to continue fighting the current regime, and often inspire Muslim Brothers with quotes from Sayyid Qutb and images of Hamas fighters.

Technically speaking, the young Muslim Brothers' targets are physical assets, not human lives. It's a rather false distinction, of course, since people can get killed whenever Molotov cocktails go flying, but this is how Muslim Brothers often rationalize their behavior to themselves and others. As young Muslim Brothers who set a police officer's home on fire told McClatchy reporter Nancy Youssef, "We tried not to kill...It's a punch to scare them." Yet in some cases, Brotherhood-affiliated Facebook groups have called for targeting individuals directly, including for assassination.

The Batman-themed "Bat Movement," which has nearly 1,900 "likes," stands out in this regard. It called on its followers to beat a television cameraman who, it alleges, is a spy for the domestic intelligence services; provided the home address and phone number of a State Security officer whom it's accused of killing protesters; and published a list of security officers in Asyut whom, it said, were wanted "dead or alive."

The "Martyr Brigades" is an even more worrying group. In its first statement, published by the "Molotov Movement" on February 10, the "Martyr Brigades" warned that it would go after "all who were involved in killing martyrs from the beginning of the coup until this day," claiming that it had the addresses of those it intended to target. Six days later, it announced that it had killed an alleged "thug" in Mansoura, and it established its own Facebook page on March 1, promising "retribution" in its first post.

This low-profile violence is likely to continue indefinitely and worsen, because young Muslim Brothers are unlikely to find other, more formal, avenues for advancing their ideology anytime soon. Egypt's military-backed government fears that permitting the Brotherhood to participate politically will enable it to return to power and seek vengeance, and by the same token Muslim Brothers are unwilling to participate in the current transition and thereby accept Morsi's ouster. The most likely outcome, at least in the short-run, is thus a desperately unpleasant stalemate: The Brotherhood cannot beat the post-Morsi regime through its current strategy, nor can the regime achieve anything approximating stability.

Eric Trager is the Wagner Fellow at The Washington Institute.

New Republic