Although many of the recently unveiled systems are foreign copies or have unproven capabilities, they show a substantial indigenous development capacity that will only accelerate once the UN ban on weapons sales is lifted—even if past sanctions snap back into action.

On August 20, Iran took the unusual step of holding its annual “Defense Industry Day” events earlier than planned in order to coincide with UN Security Council deliberations on two key issues: the soon-to-expire ban on weapons transactions with the regime, and the U.S. threat to reactivate all past sanctions by triggering the nuclear deal’s snapback mechanism. With Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in New York to make Washington’s case, Iran likely hoped to influence the conversation in its favor, uphold its reputation for defiance, and bolster its deterrence. Moreover, by unveiling a number of “high-end” military systems, the regime seemed bent on proving that there are no bottlenecks left in its production of key aerospace technologies, implying that further sanctions will not impede its progress on that front.

WHAT WAS UNVEILED?

The hastily rescheduled August 20 events sought to showcase Iran’s progress on fielding longer-range, more-versatile ballistic missiles, long-range cruise missiles, and high-performance jet engines. The exhibited systems included the following:

Haj Qasem ballistic missile. Named after the late Qods Force commander Qasem Soleimani, this weapon is touted as a medium-range derivative of the Fateh-110/Zolfaghar family of short-range tactical ballistic missiles, with a claimed range of 1,400 km—double that of the Zolfaqar’s 700 km. The Haj Qasem is believed to be a product of the Shahid Bakeri Industrial Group in Khojir or one of its subsidiaries near Yazd, all sanctioned by the United States in 2018. It appears to be a completely new missile with a wider body, probably housing a Salman solid-fuel motor with a filament-wound composite casing and pivoting nozzle thrust vectoring system. This combination was successfully tested in April on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Qased space-launch vehicle, as the rocket’s second and probably third stage.

Haj Qasem ballistic missile (Source: Islamic Republic News Agency)

According to Iran’s Defense Ministry, however, the Haj Qasem is controlled entirely using aerodynamic means—that is, via moving control surfaces only, which on their own would make the missile unmaneuverable in exoatmospheric trajectories. The use of thrust-vectoring could greatly improve its maneuverability at such high altitudes, while the use of a 500 kg separating warhead with moving control surfaces could enhance its accuracy and ability to penetrate defenses. The missile’s reentry speed is claimed to be Mach 12, with terminal velocities reaching Mach 5. If true, these numbers constitute an improvement over the Fateh-110 and are close to those of the longer-range Sejjil-2 missile. Higher terminal velocities can increase the force of impact and complicate the work of missile defenses.

Abu Mahdi naval cruise missile. This weapon is believed to be a product of the Samen al-Aemeh Industries Group (aka Naval Defense Missile Industry Group) in Parchin, which has been under U.S. sanctions since 2010. It could be either a rebranded Hoveizeh land-attack cruise missile (i.e., a second-generation Soumar, itself a copy of the Russian Kh-55) or a newer antiship version originally developed under the name Talaiyeh. Equipped with an active radar seeker head and boasting a claimed range in excess of 1,000 km, it can be fired from mobile shore or inland batteries and potentially pose a serious threat to coalition naval assets in the Arabian Sea. The Islamic Republic of Iran Navy is reportedly the intended recipient of the Abu Mahdi, but a lack of suitable maritime launch platforms means that it will be limited to land-based batteries for now.

Abu Mahdi long-range cruise missile (Source: IRNA)

According to Defense Minister Amir Hatami, Iran is also developing an air-launched cruise missile with a long standoff range. It could be an air-launched version of the smaller Quds cruise missile that was used to attack Saudi Aramco oil facilities in September 2019. Indeed, in his speech marking Defense Industry Day, President Hassan Rouhani called for increased development of air-, ground- and sea-launched cruise missiles as an eventual substitute for ballistic missiles, emphasizing their maneuverability and greater ability to evade detection and interception. General Hatami delivered a similar message, noting the increased priority Iran has assigned to long-range cruise missiles.

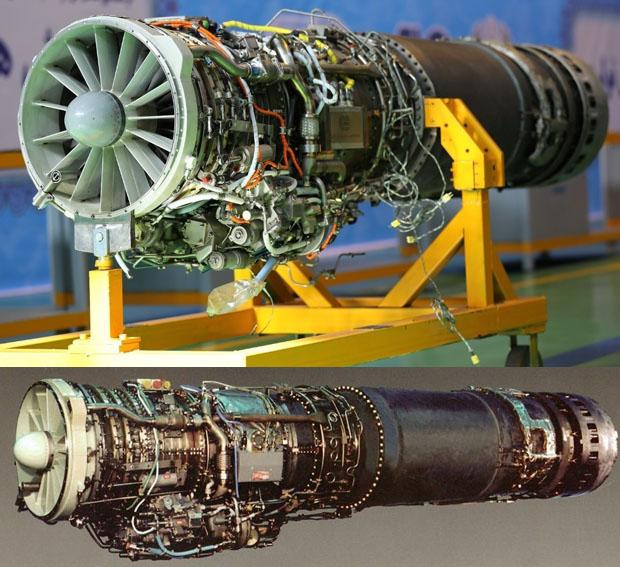

Owj turbojet engine. This engine is intended to power all of Iran’s “indigenous” jet aircraft, including the Kowsar fighter/lead-in trainer (a copy of the F-5F) and the Yassin trainer. It is a reverse-engineered version of General Electric’s venerable J85 design, originally based on 1950s technology. Iran began developing its version in the mid-1990s through Turbine Engine Manufacturing Industries (TEM) in west Tehran. Millions of J85s are currently in service around the world; Iran received hundreds of them before the 1979 revolution.

Iran’s Owj engine (top) is an exact copy of the American J85 (bottom) (Sources: Iran Defense Ministry; General Electric)

Jahesh-700 light turbofan engine. This engine is a bigger deal than the Owj given its higher technology and potential—particularly in terms of powering high-altitude, long-endurance drones. It looks very similar to the Williams International FJ33/FJ44 family of engines of the same size and thrust category, so it is most likely a direct copy of those American designs. According to General Hatami, it is “of the same type that powered the American RQ-170 drone” captured by Iran in 2011, but is “entirely designed in Iran.” He probably meant to imply that the RQ-170 Sentinel is powered by an FJ33 and that Iran managed to reverse-engineer it, even though the Sentinel is generally believed to have a different type of engine.

Iran’s Jahesh-700 engine (top) appears to be a copy of the American Williams FJ33/FJ44 (bottom) (Sources: TEM; Williams International)

The Jahesh-700 is said to incorporate single-crystal turbine blades made of special superalloys that can withstand high temperatures and achieve a longer service life. If true, the ability to manufacture single-crystal metal engine components would be a new milestone for Iran, and a potentially important step on the long path to self-sufficiency in manufacturing larger high-performance jet engines for aviation and the oil/gas/power-generation sectors. To be sure, developing larger turbofan engines that can remain efficient while sustaining much higher operating temperatures is a tall order—it would require Iran to master many other advanced technologies via highly complex and costly processes. If Tehran succeeds on that front, however, it could someday power its own advanced fighter aircraft designs with indigenous engines.

CONCLUSION

In recent years, Iran has accelerated its development of more-capable weapon systems in smaller packages, whether by obtaining/copying technologies from abroad or developing its own. If this trend continues, the regime could gradually change the balance of power in the Middle East by fielding and proliferating longer-range precision-guided weapons. Increased range would enable Iranian forces to fire from deeper inland and use unexpected trajectories, greatly improving the survivability of their missiles and launchers. They could also develop and field containerized versions of long-range cruise missiles like the Abu Mahdi with relative ease. For the most part, Iran has developed these weapons to offer a crushing second-strike capability, but they could easily be adapted to a first-strike strategy. Given the regime’s stated intention to continue advancing such systems—almost certainly with the help of technology and know-how from Russia and China—international and regional players should get more serious about establishing multilayer, 360-degree, integrated missile defense systems to address potential future Iranian advantages at the qualitative (e.g., precision) and quantitative (saturation) level.

Farzin Nadimi is an associate fellow with The Washington Institute, specializing in the security and defense affairs of Iran and the Gulf region.