Despite domestic challenges, major technical hurdles, and ongoing Israeli military interdiction, Iran still aims to transfer potent air defense systems to fellow ‘axis of resistance’ members and interconnect them.

On July 8, Syrian defense minister Ali Abdullah Ayoub and Maj. Gen. Mohammad Bagheri, chairman of Iran’s Armed Forces General Staff, signed an agreement in Damascus to significantly expand bilateral military cooperation, especially in the field of air defense. Seeing a dual need to counter aerial threats against Iran and its allies while also undermining the coalition military presence in the Middle East, Tehran has developed a strategic vision that requires effective protection and (in time) denial of airspace. Toward that end, it has repeatedly proposed to augment Iraqi, Lebanese, and now Syrian air defense systems and integrate them with its own network.

In 2019, for example, Bagheri offered to link up with Iraq’s air defense network and form a joint shell against “common enemies.” More recently, during a July 16 meeting with Lebanese president Michel Aoun, Iranian ambassador Mohammad Jalal Firouznia expressed interest in supplying the country with defensive weapons, including antiaircraft missiles. The meeting came just days after Bagheri described the new air defense agreement with Syria as another step toward pushing the United States out of the region. He has also made numerous other visits to Syria since being appointed to Iran’s top military job in 2016, seeking closer long-term military cooperation with Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

Indeed, Iran has had a significant military presence in Syria since the country’s civil war began in 2011. Most of its personnel are there in an advisory and command-and-control capacity, though some were involved in combat alongside proxy militia groups. Iran also uses Syria as a transfer hub to supply Hezbollah in neighboring Lebanon. To support this effort and rotate manpower, it uses an “air bridge”—Iranian military and civilian aircraft frequently transport personnel and materiel to Damascus International Airport, Qamishli, Latakia, and T-4 (Tiyas) air base, while Syrian flights return from Iran with weapons and ammunition for regime and militia forces.

ISRAEL IS A WRENCH IN IRAN’S PLANS

The growing scope of certain Iranian and proxy operations in Syria makes them vulnerable to Israeli air and missile strikes, which have become a regular occurrence and are seemingly unbothered by Syria’s haphazard air defenses. The defensive systems that Russia has deployed to Syria during its intervention are more formidable, but they are there to protect Russian bases, not to target Israeli aircraft.

Iran has largely been silent about these human and material losses, indicating both its frustration and its inability to prevent them. On July 16, however, General Staff spokesman Abolfazl Shekarchi warned Israel against any further strikes, then repeated Tehran’s commitment to upgrade Syria’s air defenses and strengthen the “axis of resistance” against Israeli attacks. Indeed, Iranian military leaders appear to have great confidence in the versatility and effectiveness of their domestically developed air defense systems, especially after one such unit succeeded in shooting down an American RQ-4 reconnaissance drone over the Strait of Hormuz in June 2019.

As things currently stand, however, Israel’s air force has been able to conduct a large number of successful strikes, sometimes operating inside Syria, and other times firing standoff weapons while flying over the Mediterranean Sea, Lebanon, or the Golan Heights. The Israeli army has potent strike options as well, including tactical ballistic missiles capable of reaching deep inside Syria.

AXIS OF AIR DEFENSE?

Bagheri used his latest visit to Damascus to excoriate the U.S. military presence in the Middle East, promising that Iran would continue to resist “American extortion” in the region using its new bilateral defense pact as a tool. For example, the agreement could be used to cover a wide spectrum of air defense cooperation, such as providing complete systems to Syria, upgrading its existing systems, or integrating the two countries’ air defense networks (though the latter would be difficult to achieve without Iraq’s cooperation).

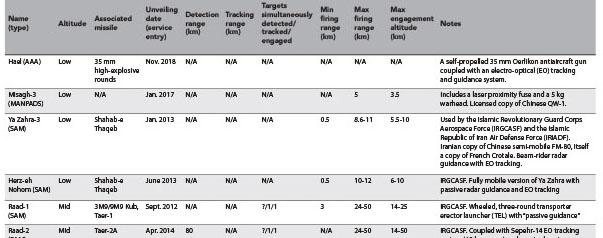

More specifically, Iran can offer Syria low- and high-altitude surface-to-air missile systems capable of intercepting targets as far away as 200 km and at altitudes up to 30 km (see table). It can also offer to send some of the data fusion/management capabilities and passive detection systems it has unveiled in recent years.

Syria’s current air defense forces are mostly limited to older Russian systems such as the S-125 (SA-3), 2K12 (SA-6), S-75 (SA-2), and S-200 (SA-5), along with more modern SA-11 Buk and SA-17 Buk-M batteries augmented by Pantsir-S1 point defense systems (the latter paid for by Iran). In late 2018, Moscow completed delivery of the S-300 (SA-20) system to Damascus. At the time, U.S. officials were concerned the delivery would embolden Iran, but the system is reportedly still under Russian control and not operational.

Iran has a number of S-200, S-75/HQ-2, and 2K12 systems in service back home and has upgraded them over the years, so it could offer to upgrade Syria’s batteries as well. In addition, it could send Assad indigenously developed systems such as the Raad, Tabas, 15th of Khordad, Talash, and 3rd of Khordad (the type used to shoot down the U.S. drone). Tehran might also intend to help Syria set up local production/assembly lines for such systems, most likely in underground facilities (similar production capabilities could conceivably be offered to Iraq or even Hezbollah).

Iran’s longest-range and supposedly most-advanced air defense system, the Bavar-373, is still under development and has yet to enter full-scale production. Iran claims that the system is comparable to an American Patriot missile battery and superior to Russia’s S-300PMU-2, but for now all it can offer Syria is to deploy an unproven example there for testing and evaluation purposes under operational conditions. Of course, such exposure would also give adversaries a chance to observe the system in action and hone their tactics against it.

As for which of these theoretical transfers will actually happen, that depends on how well Tehran can cope with formidable challenges at home and inside Syria. Iranian leaders clearly want to expand their deterrence and strategic depth beyond the limits set by their ballistic missile arsenal, and fielding more-advanced, longer-range air defense systems would be their method of choice. At the same time, however, they seem increasingly threatened by a host of foreign and domestic perils, including what looks like a campaign of sabotage against their nuclear program and industrial infrastructure. Adding to their concerns is a sobering military reality: Israel is determined to prevent them from transferring any new systems to Syria, and sending them now would only widen the considerable gaps in Iran’s own air defense coverage.

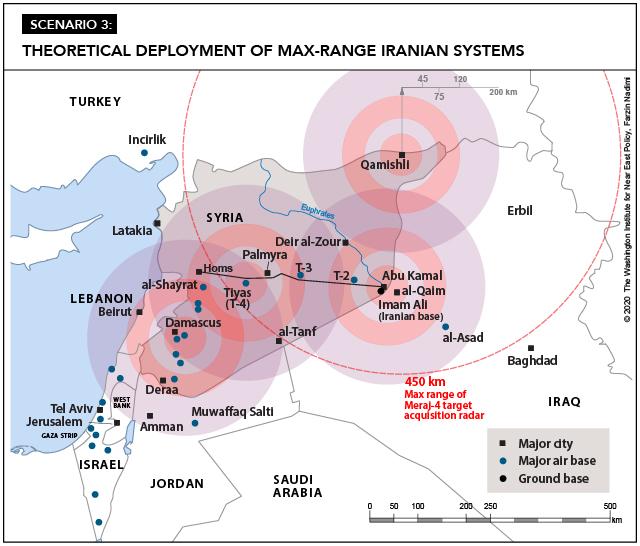

Under these circumstances, it is doubtful that Tehran will be able to transfer substantial amounts of this equipment to Syria in the near term. The best they can hope for (if anything) is a pair of air defense bubbles: one at Imam Ali base near the Abu Kamal border crossing, and another at T-4 air base or in the Damascus area.

Click on maps to see larger versions

This is a far cry from their ideal scenario: establishing at least a dozen mobile medium-to-long-range missile batteries and radars around Syria to protect joint bases and storage hubs from Israeli raids.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Per paragraph 6b, Annex B of UN Security Council Resolution 2231, Iran is not allowed to transfer air defense systems to any country without the council’s permission; therefore, as long as this ban is in place, all states should take the necessary measures to enforce it. Unfortunately, the ban is scheduled to expire on October 18, but the United States has stepped up its diplomatic efforts to make sure that arms sanctions remain in place indefinitely.

The international community also has other grounds for stopping the proliferation of antiaircraft systems from Iran. On July 16, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency extended its ban on all commercial overflights of Iranian-controlled airspace below 25,000 feet (7,620 meters) for another six months due to concerns about “hazardous security” there. The EU move—which reemphasized a directive originally issued by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration—came just as an increasingly tense Iran put parts of its air defense system on high alert, and mere months after one of its SAM batteries accidentally shot down a Ukrainian airliner. Going forward, Washington should reassert its commitment to aviation safety in the region under Annex 17 to the Chicago Convention (“Safeguarding International Civil Aviation Against Acts of Unlawful Interference”), using the standards therein as justification to prevent Iran from exporting and controlling air defense systems that have already proven a threat to civil aviation.

Farzin Nadimi is an associate fellow with The Washington Institute, specializing in the security and defense affairs of Iran and the Gulf region.