Tehran’s decision to renege on some of its nuclear commitments heralds a new period of disturbingly ambiguous announcements.

On May 15, one year after the United States withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal, Iranian news agencies reported that Tehran had officially stopped honoring some of the commitments it made under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. The remaining parties to the JCPOA—Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia, and the European Union—were informed of the decision the previous week.

Such announcements are especially worrisome given the abundant gray areas within the text of the JCPOA, many of which are ripe for exploitation if Iran tries to advance its nuclear program and pressure other countries without triggering punitive action. On May 8, for example, President Hassan Rouhani stated that Iran was planning to hold onto its stockpiles of excess uranium and heavy water in response to U.S. sanctions on the shipment of these materials—a move that would not immediately violate the deal but is out of line with the regime’s general commitment to send these items abroad. Of greater concern, Rouhani warned that unless the remaining JCPOA countries protect Iran’s economy from U.S. sanctions within sixty days, higher-level uranium enrichment would resume.

The JCPOA is a highly technical document, so staying on top of which specific activities it prohibits and allows can be difficult for non-experts. The following is intended as a layperson’s guide to the vocabulary and arguments that will likely be used to justify or criticize Iran’s nuclear decisions in the coming weeks, especially if diplomatic tensions continue to rise.

WHAT DOES THE JCPOA SAY ABOUT NUCLEAR WEAPONS?

According to the agreement’s preface, “Iran reaffirms that under no circumstances will [it] ever seek, develop or acquire any nuclear weapons.” Yet the long-term durability of this pledge has always been a diplomatic fiction—Tehran believed that the deal’s overall effect was to preserve its standing as an emerging nuclear power while easing economic sanctions. The provision’s hollowness was reiterated last year after Israel seized part of Iran’s nuclear archive, exposing details of the regime’s apparently successful attempts between 1985 and 2003 to develop much of the technical know-how required to produce a nuclear weapon.

What makes such activities so difficult to prevent is that the skillset for developing a peaceful nuclear program overlaps considerably with what is needed for a military program that manufactures nuclear weapons. An atomic bomb requires either 25 kilograms of high-enriched uranium (HEU) or 8 kilograms of plutonium. Both HEU and low-enriched uranium are typically made with centrifuges, while plutonium is a byproduct found in spent nuclear fuel. (HEU is defined as uranium containing at least 20 percent of the fissile isotope U-235, though a bomb ideally needs 90 percent; low-enriched uranium contains less than 20 percent U-235, and at around 3.5 percent is often used for reactor fuel.) The best way to make plutonium is to place unenriched uranium in a reactor that also contains “heavy water” (water rich in deuterium oxide). Iran apparently prefers uranium enrichment because the technological challenges of plutonium production are greater.

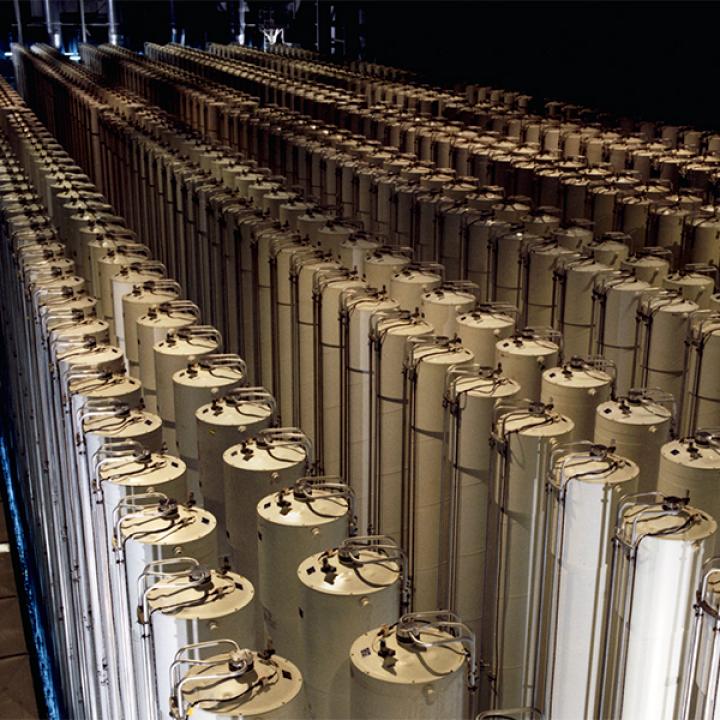

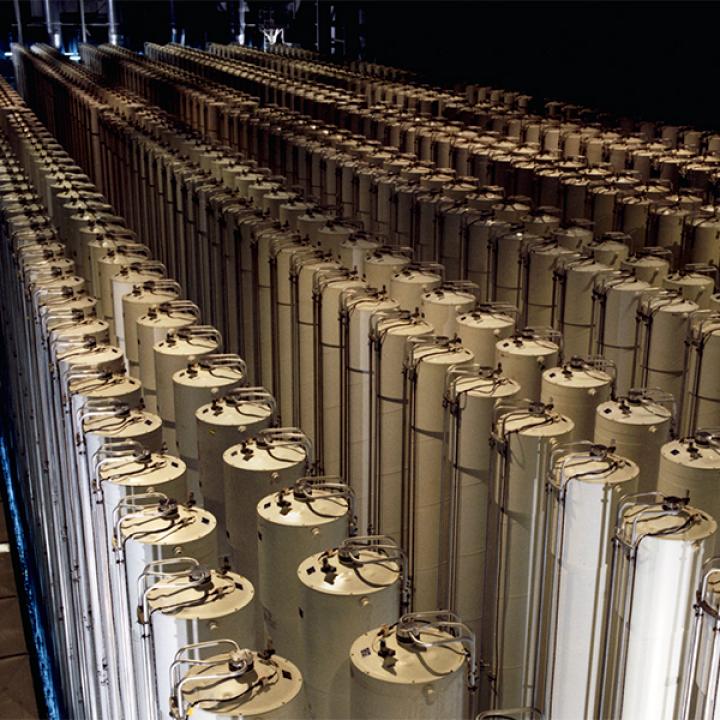

At the time of the agreement, observers estimated that Iran was close to being able to produce enough HEU for one bomb within a few weeks, known as “breakout time.” The agreement turned the dial on this calculation by limiting the quantities of uranium that could be enriched, the level of enrichment, and the type of centrifuge used. Any Iranian evasion of these boundaries, even rhetorical, should be a great concern. An unclassified rule of thumb is that 5,000 first-generation centrifuges can produce enough HEU for one nuclear weapon in about six months. Although Iran still has enough centrifuges, they are not currently configured in arrangements (cascades) for higher enrichment.

In this context, the following JCPOA provisions are most relevant:

- Iran is barred from enriching uranium beyond 3.67 percent, and can stockpile or use only 300 kilograms of such material. This figure includes compounds such as uranium hexafluoride, which in its gaseous form is the feedstock of centrifuges.

- The maximum number of centrifuges Iran can use for enrichment is 5,060.

- The only centrifuge Iran can use for enrichment is its first-generation IR-1, a copy of the P-1 design that Pakistani scientists acquired illegally from Europe.

- Iran can conduct some R&D work on more-advanced centrifuges, but only to a limited degree.

- Iran’s Arak research reactor was modified to minimize its plutonium risk.

- These and other JCPOA restrictions will expire sometime between 2025 and 2030; Western negotiators originally hoped that Iran’s desire to develop a nuclear weapons capability would abate by then.

IRAN’S CURRENT STRATEGY

Given Rouhani’s May 8 remarks, the regime may intend to rebuild its capacity to make a nuclear weapon. Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif added fuel to such speculation on April 28 when he stated, “The Islamic Republic’s choices are numerous and the country’s authorities are considering them...Leaving the NPT is one of them.” He was referring to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, by which nuclear weapon states agree to supply civilian nuclear technology to other countries in return for their commitment not to develop such weapons. Iran signed the treaty before the 1979 revolution.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei echoed Rouhani’s point on May 14: “Achieving 20 percent enrichment is the most difficult part; the next steps are easier,” he said, suggesting a surprising familiarity with nuclear physics and essentially reminding the West how quickly Iran could produce weapons-grade material if it resumed full-scale enrichment. Indeed, at 20 percent enrichment, most of the work of separating fissile U-235 atoms from natural uranium atoms (U-238) is done, as the following illustration shows:

KEY INSTALLATIONS

Arak research reactor. Before the JCPOA, this facility was capable of producing plutonium but was not yet active. On May 8, the Supreme National Security Council stated that Iran would “cease implementation of measures related to the modernization of the Arak heavy water reactor.” According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, the reactor’s insides (“calandria”) have been removed and rendered inoperable.

Bushehr. The Russian-supplied power reactor facility on the Persian Gulf coast is separate from Western concerns about military nuclear activities and is currently still operating. Plans continue for Moscow to build more power reactors at the site.

Fordow. This centrifuge plant was built deep inside a mountain in central Iran, making it immune to most military attacks. Yet the United States now has conventional bombs capable of penetrating the site, and it may be vulnerable to cyberattack as well (in the past, the U.S.-Israeli Stuxnet virus interrupted Iranian centrifuge operations for some time). Although Fordow’s centrifuges are currently used for non-nuclear purposes, Iranian nuclear chief Ali Akhbar Salehi warned last December that this could change: “We currently have 1,044 centrifuges in Fordow, and if the establishment wants, we will restart 20 percent uranium enrichment in Fordow.”

Natanz. This is the site of Iran’s main centrifuge plant, though only a third of its original 19,000 centrifuges are operating. If Iran wants to resume industrial-scale enrichment, this is where it would take place. On May 20, a spokesperson for the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran stated that the amount of 3.67 percent uranium produced at the plant would be quadrupled, going “beyond the 300 kilogram limit in the not too distant future.”

Parchin. The photos and other materials that Israel seized from this military site outside Tehran indicate that the regime conducted experiments there to determine whether a bomb design would work.

Tehran Research Reactor. This facility uses 20 percent enriched uranium fuel, currently imported. Iran has often argued that it should be able to produce its own enriched fuel for this installation, which it says is important for civil research and medical isotope production.

PRINCIPAL CONCERNS FOR WASHINGTON

Despite its rhetoric to the contrary, Iran would probably need many months to rebuild its previous enrichment capacity. Enrichment is nevertheless the greatest worry for the United States given its potential to put the regime right back on the path to quick breakout.

Tehran’s comments about heavy water are probably of less concern. Reprocessing spent fuel to obtain plutonium is a great challenge and Iran has no such a facility.

Iran’s progress on developing advanced centrifuges—which can enrich uranium to higher levels more quickly and in greater quantity—is lacking so far. The main technical challenges of centrifuge design are maximizing their speed and height while avoiding breakdowns. Overcoming these obstacles is a matter of using the appropriate construction materials (special steel or carbon fiber, depending on the machine part in question) and going through considerable engineering trial and error (unless Iran obtains leaked secrets from specialist foreign firms).

Perhaps the main challenge for Washington is that Iran’s nuclear messaging often sounds plausibly innocent. The American public and perhaps even elements of the policy community have limited comprehension of the technical issues behind such messaging. So far, Tehran seems to be calculating that it can win the verbal battle, allowing it to get away with technical deeds that may once again place it on the threshold of becoming a nuclear weapons state.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Gulf and Energy Policy Program at The Washington Institute.