- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3120

No More Turkish Veto on Idlib Offensive?

Ankara’s calculations about the rebel province appear to have shifted, though it still hopes to use the situation as leverage for constraining the YPG and preventing another refugee influx.

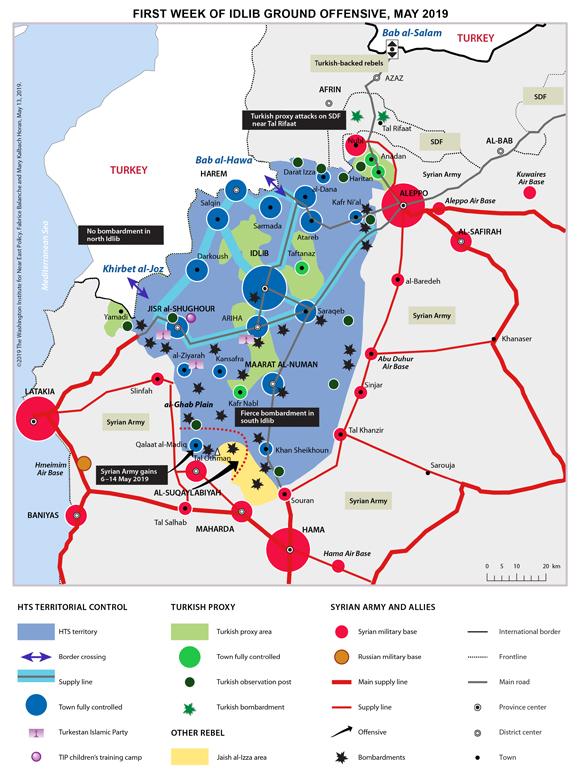

On May 6, the Syrian army seized Tal Othman, a strategic hill northwest of Hama, thus beginning a ground offensive aimed at regaining control in some or all of Idlib province. Several localities have since fallen, including Qalaat al-Madiq, a stronghold of the rebellion since 2011. Previously, aviation and artillery had pounded southwest Idlib for more than a month in order to weaken rebel defenses and push civilians to flee. Apart from some sporadic shelling in Idlib city and the western outskirts of Aleppo, practically no bombardment has been seen north of the Aleppo-Latakia highway, suggesting that the regime’s current offensive may be limited to the southern half of the province. Bashar al-Assad’s ultimate goal of eradicating the Sunni rebellion’s last major stronghold remains the same, but he (along with Russia and Turkey) may still be constrained by various strategic factors.

Click on map to view high-resolution version.

REGIME FORCES HAVE GROWN STRONGER

It is difficult to know how many troops are involved in the current campaign, but the Assad regime faces no critical danger elsewhere in the country, so it is reasonable to assume that the bulk of its forces have been committed to Idlib. Gen. Suhail al-Hassan of the elite Tiger Forces is likely leading the operation. Although Hezbollah and other Shia militias are participating to help balance the deficiencies of Syrian troops, the army has recently strengthened itself with former rebels and new conscripts from Deraa and East Ghouta. To test the loyalty of these new forces, the regime tasked them with storming Tal Othman and Qalaat al-Madiq.

The Russian air force is strongly supporting the offensive from Hmeimim base around fifty kilometers to the west. Meanwhile, artillery fire from the eastern foothills of the Alawite Mountains can reach the entirety of al-Ghab plain, where the Syrian army is separated from the rebels by the Orontes River. Artillery batteries in Aleppo and Abu Duhur have fired on rebel positions as well, though it is unclear whether they are signaling an imminent ground offensive from the east or simply keeping jihadist forces at a distance during the southwestern campaign.

AL-QAEDA ON THE RISE, TURKEY’S PROXIES GONE

More than 50,000 well-armed, battle-hardened rebel fighters remain in Idlib. Around 20,000-30,000 of them belong to the jihadist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), mostly Syrians recruited in Idlib and veterans from various rebel territories retaken by the regime in past years. Foreigners have constituted a minority in its ranks ever since the group distanced itself from al-Qaeda and confined its jihad to Syria.

Nevertheless, HTS is currently partnered with 5,000-10,000 al-Qaeda allies, including Chinese Uighurs from the Turkestan Islamic Party (3,000 fighters) who began settling around Jisr al-Shughour in 2015. This faction has backed HTS in all battles over the past few years, even sending suicide bombers to breach the siege of East Aleppo. Huras al-Din (2,000 members) has fought alongside HTS as well, despite formally splitting from the group in 2017 after HTS broke its oath of allegiance to al-Qaeda. Huras al-Din’s foreign fighters have refused to help HTS subjugate other rebel groups in Idlib, in line with the mandates of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. Yet they have no qualms about partnering with the group against the Assad regime.

The National Front for Liberation, a rebel coalition created by Turkey in 2017, no longer exists after the HTS alliance completely defeated it in February. Its leaders have fled to al-Bab and Afrin, though HTS has allowed the coalition’s local fighters to remain in Idlib because it needs them against the Syrian army. Two groups remained neutral in this inter-rebel fighting—Failaq al-Sham and Jaish al-Izza—but both have seemingly accepted the HTS victory over the National Front. Jaish al-Izza is a former Free Syrian Army affiliate with 2,000-3,000 combatants in southwest Idlib. It does not claim any particular ideology, but it has allied with jihadist groups in all offensives against the Syrian army (and previously enjoyed broad support from the Pentagon, including the provision of TOW antitank missiles).

A SANCTUARY IN NORTH IDLIB?

In general, south Idlib is more fragile than the north—partly because recent fighting between HTS and the National Front weakened rebel positions there, but also because Jaish al-Izza and other southern groups have no love lost for HTS and may be willing to strike deals with the regime. The army would have much more trouble attacking north Idlib, which is an old and largely untouched stronghold for HTS and other jihadists.

Another reason why Assad may leave the north in peace for now is so that fleeing civilians and rebels from the south can take refuge there. Throughout the war, the army has typically left a way out for rebel forces so they do not feel compelled to fight to the death. Perhaps more important in this case, however, the regime does not want to upset Turkey, which would face a new wave of refugees if north Idlib were under threat.

According to the UN, around half of Idlib’s 3 million residents are classified as internally displaced persons, many of them hailing from Aleppo, Ghouta, Homs, and Deraa. These IDPs tend to support the rebellion and have no desire to go back under Assad’s control. The Syria-Turkey border is closed with a wall, but hundreds of thousands of IDPs have been piling up nearby in informal camps since 2012, hoping that proximity to the border would protect them from bombing. If these refugees tried to cross the frontier by force, Ankara would not be able to prevent their passage without a slaughter.

At the same time, Turkey is unwilling to increase the massive number of Syrian refugees it already hosts—3.8 million at last count. To avoid a worst-case scenario, Ankara has likely obtained approval from Russia to turn the Syrian side of the Idlib border into a refugee sanctuary if necessary.

TURKEY’S VETO, RUSSIA’S CALCULUS

Until recently, Turkey fiercely opposed any Syrian offensive against Idlib—partly because of the refugee issue, but mainly because President Recep Tayyip Erdogan did not want to distract from his primary goal of keeping the Kurdish People’s Defense Units (YPG) from cementing control over Syria’s northeast frontier. When an Idlib campaign appeared imminent last September, Turkish and Russian officials reached a ceasefire agreement in Sochi to stay Assad’s hand there.

In December, however, the United States announced that it would be withdrawing from northeast Syria, seemingly abandoning its longtime YPG partners. Subsequent talks regarding the area’s future may have alleviated some of Turkey’s fears about the Kurds, perhaps lessening its concern that an Idlib offensive would be a distraction. Erdogan has sternly denounced Russia for allowing the current operations, but it is unclear whether he is more focused on blustering to save face publicly, genuinely warning Assad to stay out of north Idlib due to Turkey’s internal security concerns, or asserting his role in Syria’s long-term stabilization process.

Whatever the case, he was unable to enforce key terms of the Sochi ceasefire, such as the creation of a twenty-kilometer demilitarized zone between rebel and regime forces in Idlib, and free movement on the Aleppo-Latakia and Aleppo-Hama highways. The rebels had no desire to abandon their defensive lines or lose the colossal sums they draw from the movement of goods on those motorways. And once the pro-Turkish National Front utterly failed to wrest influence away from HTS, Erdogan was left with little tactical reason to continue opposing a regime offensive.

These failures also stem from the fact that President Vladimir Putin treated the Sochi agreement not as a genuine accord to be honored for the long term, but rather as a temporary means of keeping Turkey on his side at a time when Erdogan was feeling especially vindictive toward Washington for supporting the YPG. Moreover, Putin might believe that attacking Idlib and stoking potential refugee/jihadist flows toward Turkey could pressure Ankara on other bilateral imperatives, such as completing its controversial purchase of Russian S-400 missile systems.

Going forward, Erdogan may still seek to use Idlib as leverage for guaranteeing his freedom of action against the YPG. Russia has granted such guarantees in the past (e.g., in Afrin last winter) and may have done so again this month—on May 4, Turkish proxy forces began an offensive against a YPG stronghold in Tal Rifaat north of Aleppo.

In other words, the Sunni rebels and the Kurds are the main currency of exchange between Turkey and Russia, so their fate is intimately linked. In these circumstances, Turkey understandably does not want Assad to completely retake Idlib right away, since that could affect the pace of America’s withdrawal from Syria and the U.S. special envoy’s ability to peacefully resolve the problems between Ankara and the YPG. Russia may give in to that leverage temporarily if Turkey’s objections to the offensive grow louder. In the long term, however, it is difficult to imagine Moscow accepting the presence of a jihadist stronghold in Idlib unless HTS truly breaks with al-Qaeda—which is also difficult to imagine. Therefore, the “Islamic Emirate” in Idlib could wind up much like the Islamic State did in Raqqa.

Fabrice Balanche is an assistant professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, and author of the 2018 Washington Institute monograph Sectarianism in Syria's Civil War: A Geopolitical Study.