- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3211

Riyadh Agreement Delivers Political Gains in Yemen, But Implementation Less Certain

The new agreement will score a win if it brings the most important players to the table for wider talks, but implementing its often-vague provisions so quickly will prove challenging.

After numerous delays, the Hadi government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) have signed a power-sharing agreement in Riyadh that provides the legitimacy that each of them craved, while perhaps temporarily halting their hostilities in Yemen. Yet the vague language of the November 5 document portends difficulties in implementation.

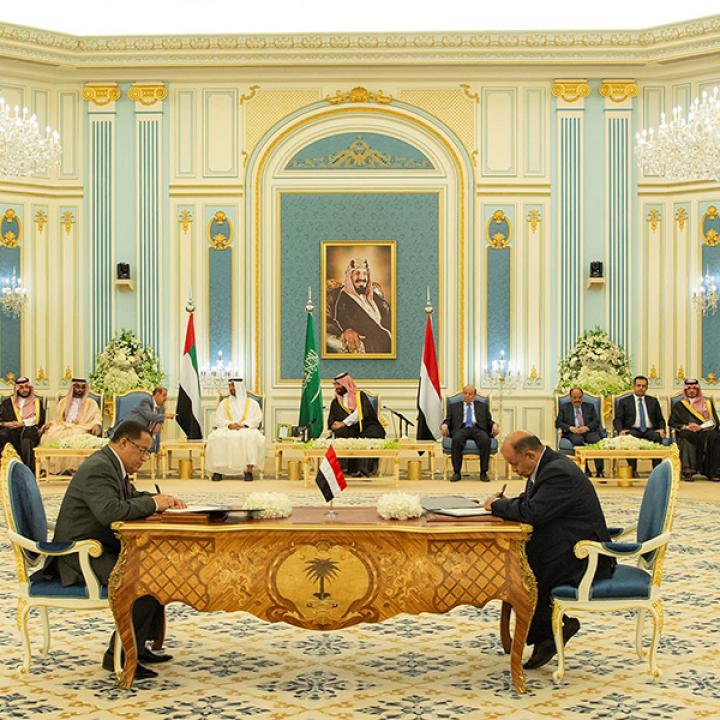

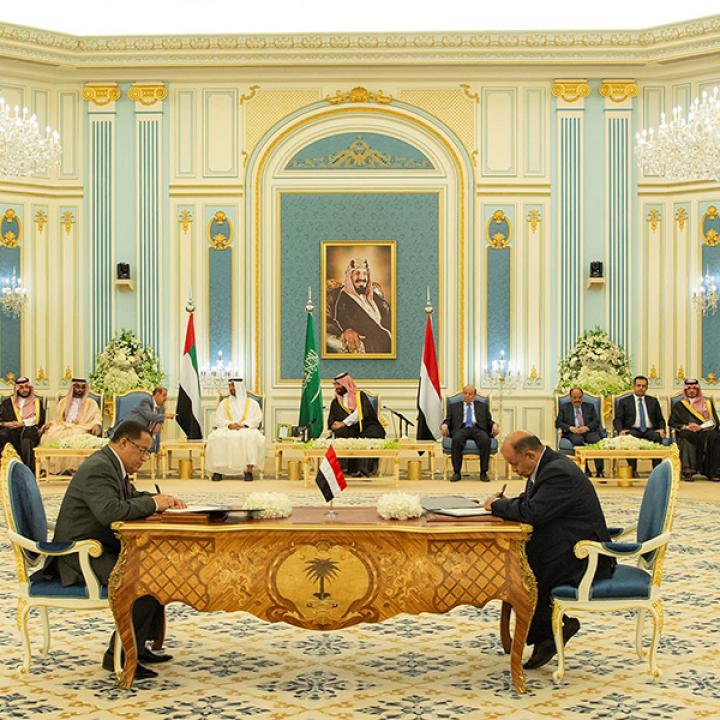

An even more worrisome obstacle is the utter lack of trust between the two parties, who did not negotiate the agreement face to face. Instead, Saudi negotiators have been going back and forth between them since August 20, and the signing ceremony may be the first time the parties have been in the same room since violence erupted this summer. This level of distrust may limit their ability to meet the document’s call for organizing under a single political and military chain of command, even with Saudi mediation.

POLITICAL WINS

The four-page agreement cites the common objective of defeating the Houthi rebels, then lays out a series of general mandates that grants each party the legitimacy it seeks. For the Hadi government, the document states that all military and security forces, including those aligned with the STC, are to fall under the Ministry of Defense. This is a win for President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi, who demanded that the STC explicitly recognize his role as the leader of Yemen’s only internationally legitimate government.

For the STC, the agreement says they will participate on the government’s side in final peace negotiations with the Houthis. This is a compromise, since their ultimate goal remains for south Yemen to secede from the north. Yet without international support for secession at present, and having lost a battle to Hadi-backed forces in the critical province of Shabwa on August 26, the STC decided it was best to secure a seat at the table for final talks. In their view, this grants them legitimacy as a representative of southern desires and will ensure those desires are not marginalized. Having the southern issue on the table in final talks will in turn allow them to fight another day for a referendum on secession.

IMPLEMENTATION DIFFICULTIES

The arrangements laid out in the document are designed to stop the fighting and integrate the STC’s political, security, and military forces under a single Yemeni command. Yet these measures fall under exceptionally tight thirty-, sixty-, or ninety-day timetables and are couched in vague language—echoing the lack of specificity that has dogged the stalemated Stockholm accord that Hadi and the Houthis agreed to in December 2018.

For example, today’s agreement stipulates that Hadi appoint a new technocratic government with up to twenty-four ministers in the next thirty days. Half must be from the south, but the agreement does not explicitly say they must be STC-aligned, nor does it make clear who will fill the most important roles such as prime minister, interior minister, and defense minister. Since a misstep on those appointments could undermine the entire accord, it is likely that negotiations on these details are under way or already agreed upon.

Moreover, the document indicates that individuals involved in the fighting in Aden since August are not eligible for ministerial appointments. Although this clause was meant as a confidence-building measure, it excludes some powerful figures and may have the unintended effect of steering them toward the role of spoilers in the future. On a related note, the agreement calls for all medium and heavy weapons to be put in military depots under the supervision of the coalition in Aden within fifteen days, but it is unclear how the government or STC will collect such weapons, especially from those parties who feel excluded.

The agreement also fails to deal with other issues that will inevitably arise when trying to unify rival forces. For example, it states that the Facility Protection Forces, who are responsible for securing key installations such as the Central Bank, ports, and refineries, will be chosen either from their current ranks, Hadi’s forces, or the STC’s forces. This kind of inexact language, which is littered throughout the document, kicks the can of tough, tactical decisionmaking down the road—a road that is only thirty days long.

Adding to the confusion, the sequencing of various components is unclear and is widely believed to be one of the factors behind the agreement’s delay, along with concerns over major ministerial appointments. One can only hope that the Saudis already began negotiating such tactical decisions behind the scenes well before this week.

THE BURDEN IS ON THE SAUDIS

Indeed, implementation will likely fall entirely on Riyadh’s shoulders. To demonstrate unity of purpose, Emirati crown prince Muhammad bin Zayed had a front-and-center seat next to Saudi crown prince Muhammad bin Salman at the signing ceremony. Yet the UAE is not mentioned in the agreement, its forces have continued to draw down in Yemen, and its leaders appear to have left management of the Hadi-STC negotiations to the Saudis.

Meanwhile, Hadi-STC discussions about implementation seem far off. During today’s ceremony, President Hadi and STC head Aidarous al-Zubaidi left the signing to lower-level officials and do not appear to have shaken hands. Afterward, they met with the Saudi crown prince separately, suggesting they may continue relying on Saudi-led shuttle diplomacy going forward. It is difficult to fathom Hadi and STC forces mixing nicely together—let alone cooperating effectively to counter the Houthis—if their leadership will not even shake hands. Indeed, the Houthis will be closely monitoring Saudi efforts at implementation over the next few weeks to see if a unified, capable coalition arises.

BRINGING FIVE PARTIES TO THE TABLE

On a positive note, if the agreement is implemented even partially, it has the potential to create better conditions for UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths, since any comprehensive peace talks he is able to convene would now include parties that might otherwise act as spoilers. For example, the Hadi delegation to such talks could plausibly include representatives from the Islah Party (assuming they retain some ministerial positions) and the STC, while the Houthi delegation would continue to include representatives from the General People’s Congress Party. Although Yemen’s increasing fragmentation lends itself to additional spoilers, their impact would be greatly mitigated if the above key players are similarly invested in successful rather than failed talks. Thus, even if the Riyadh agreement suffers the same halting implementation as the Stockholm agreement, it may still be a political win that moves the Yemen war closer to some kind of resolution.

Elana DeLozier is a research fellow in The Washington Institute’s Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy.