Riyadh’s negotiation efforts in Yemen’s north and south have faltered, raising questions about its ability to single-handedly shepherd the country toward peace.

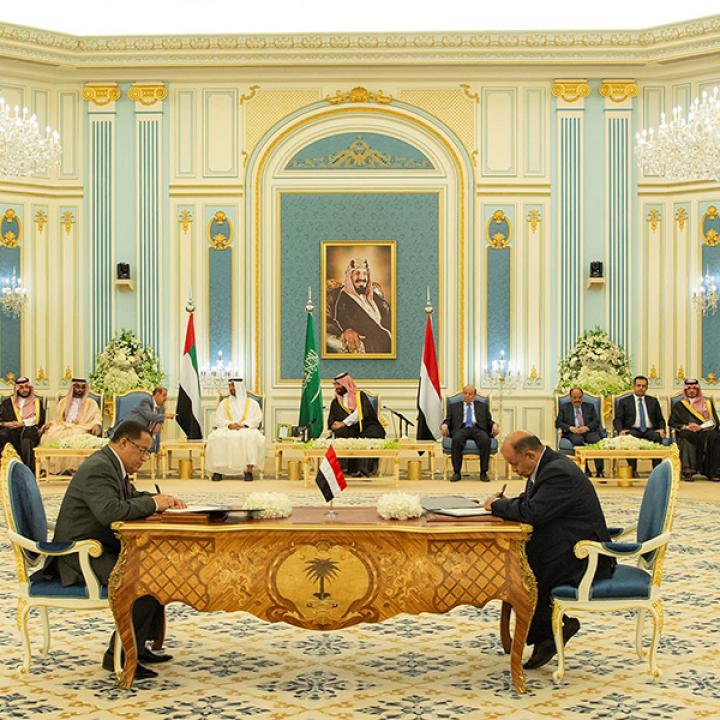

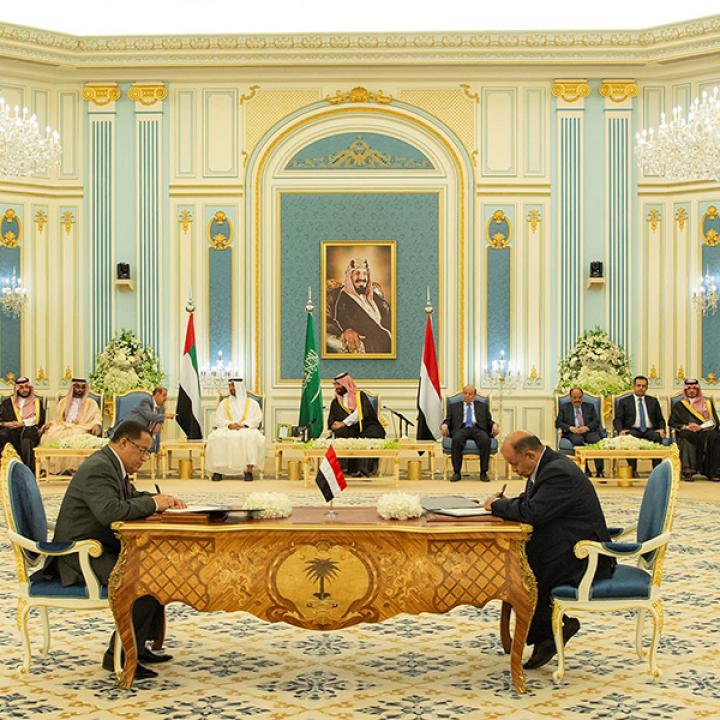

Nearly six months after Saudi Arabia negotiated the Riyadh Agreement to integrate the Southern Transitional Council and Yemeni government under a single political and military command, the deal has been dealt a serious blow. On April 25, the STC boldly declared its “autonomous administration of the South”—evidence that the council and Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi’s government are as much at odds today as they were at the signing ceremony last November. The disappointing turn comes after Houthi forces in the north refused to join a Saudi ceasefire on April 9, instead continuing their push toward the government’s resource-rich stronghold in Marib province.

This double blow is a watershed in a months-long experiment that has put Saudi Arabia at the helm of negotiations in Yemen. Last fall, the kingdom began direct talks with the Houthis and took over responsibility for patching up disputes between the Hadi government and STC. The hope was that Riyadh would have enough leverage to corral all parties into UN-brokered peace talks. That has not been the case, suggesting the kingdom needs to leverage the strengths of other parties in order to end the war.

SAUDIS AT THE HELM

With the UN bogged down in the ill-fated 2018 Stockholm Agreement, the Saudis have largely been leading diplomatic efforts in Yemen since last summer. Two events in 2019 propelled them to the forefront. First, the UAE military drawdown shifted responsibility for keeping the peace among coalition partners onto Riyadh. By August, only weeks after this pullout became official, a major attack killed an STC commander. The STC harbored suspicions that a government-aligned faction was involved, igniting the council’s latent conflict with Hadi and forcing Riyadh to act as mediator. Second, the September attacks on Saudi oil facilities in Abqaiq, widely believed to come from Iran, spurred the kingdom to launch direct talks with the Houthis in order to protect its territory and exit the war.

The Houthi talks have been fraught. The two sides differ on diplomatic strategy: the Houthis prefer a holistic approach to negotiations, whereas the Saudis prefer a piecemeal, confidence-building approach. There is also little trust between them—the Houthis temporarily halted attacks into Saudi territory in September, and the coalition reduced its airstrikes in response, but the parties were unable to reach a full-fledged joint ceasefire inside Yemen. The Houthis eventually resumed attacks against the kingdom, and ground fighting ramped up in Yemen. Since January, they have wrested strategic territory from the government and continue to push into Marib. By the time Saudi Arabia announced its unilateral April 9 ceasefire, the rebel goalposts had changed—the Houthis refused to join the deal until the coalition lifts its blockade on Yemen. The ceasefire has been extended for another month, but the Houthis still have little incentive to join it.

Last year’s Riyadh Agreement has not fared much better. The power-sharing deal provided notable political wins to the Hadi government and the STC, but the document itself was full of inexact language, had unclear sequencing, and failed to define fundamental matters such as what “integrating forces” would mean in practice. Both sides have taken maximalist political positions since then, and their efforts to defeat each other militarily have been stymied by Saudi interventions. As a result, the agreement has yet to be implemented.

Adding to this mess, floods ravaged Aden and other areas last week, showing just how badly residents in the south are suffering from the lack of leadership. The Hadi government is based in faraway Riyadh, and its cabinet has seen its legitimacy continue to shrink as it waits to be replaced under the terms of the Riyadh Agreement. STC leaders are stuck in Abu Dhabi due to coronavirus travel restrictions. Each side has prevented the other’s officials from returning to Aden. Unsurprisingly, protestors at a recent public demonstration railed against absentee officials on both sides.

Whether to break the stalemate with Riyadh or signal leadership amid the flooding, the STC has now declared a state of emergency and “self-rule” in the south. The Hadi government quickly condemned the move—but so did the Saudi-led coalition, the Emirati government, the Gulf Cooperation Council, the United States, the European Union, and the governors of three eastern Yemeni provinces (Hadramawt, Shabwa, and al-Mahra). The coalition and others also urged all parties to “work rapidly” toward implementing the Riyadh Agreement, though without explaining how they should overcome the hurdles.

NO LEVERAGE, NO PROGRESS

Last fall, many saw the Saudi entry into negotiations as a cause for hope. According to that narrative, every party—including the Houthis—desired a relationship with Riyadh, and the kingdom had ample largesse to offer them. Surely that meant the Saudis would have more success than the UN. Yet their inability to resolve Hadi-STC disputes or reach a ceasefire deal with the Houthis has exposed their lack of leverage.

For example, one common refrain is that the Saudis can strong-arm President Hadi when needed—indeed, they did just that when getting him to sign the Stockholm Agreement in December 2018. He ultimately balked at implementation, however. The pattern then repeated itself with the Riyadh Agreement. The conclusion seems clear: the Saudis can strong-arm a signature but not implementation, suggesting their leverage over the Hadi government will not advance peace any further on its own.

Conventional wisdom also insinuates that the UAE can strong-arm the STC. But once Abu Dhabi took a hands-off approach to Yemen last fall, the Saudis became the council’s foremost interlocutor. The Emiratis remain an STC ally, but they do not seem to be heavily involved in southern decisionmaking related to the Riyadh Agreement. If they have leverage, they are choosing not to use it.

Given all these issues, the balance of leverage in Saudi-Houthi talks has tilted squarely in the latter’s favor. Meanwhile, the Saudis have limited options to get out of a war that has cost them hundreds of millions per day and amplified their fears about Iranian influence in the Arabian Peninsula. A unilateral military withdrawal would likely guarantee an Iranian-backed Houthi force across their border for years to come, while a cut-and-run lifting of the economic blockade would allow Tehran to more readily resupply the rebels with advanced weapons.

A GROUP EFFORT

The past six months have shown that the Saudis are hard-pressed to end the war on their own. Even the largesse they have doled out to Yemen’s Central Bank, the Hadi government, and the humanitarian aid effort has not moved the needle on any of the negotiations.

Instead, Riyadh may need to take a more deliberate approach to negotiating the war’s end by relying on leverage acquired from the UN, the United States, Britain, the EU, the UAE, and Oman. Each of these parties has relationships or capabilities that can facilitate Saudi efforts. The UAE has a strong relationship with the STC. Oman is actively engaged under new sultan Haitham bin Tariq al-Said and has regular access to the Houthis in Muscat. The United States and Britain can bring expertise on the details of a postwar plan, such as disarmament. The EU can provide cooperation frameworks or perhaps mediate between the Saudis and Houthis, in part to quell the rebel complaint that the kingdom cannot be a participant in talks and a mediator at the same time. Gulf neighbors can bring reconstruction money and expertise. And the UN has a deep sense of each party’s needs and redlines.

In some cases, Riyadh may find that having its partners lean into their relationships with certain Yemeni factions would help; in other cases, less foreign interference or funding might be best. But the fact remains that these parties are already involved unilaterally, and Riyadh has already been reaching out to many of them individually, with diminishing returns. Therefore, any peace strategy would be better served if the deliberations shaping it were more of a collective effort, even as foreign actors strive to avoid the appearance of meddling in Yemen’s internal affairs.

The urgency of such cooperation has grown because events are moving faster than Riyadh’s decisionmaking. The focus should therefore shift to corralling international partners whose combined relationships can better incentivize Yemen’s factions to reach a peaceful resolution. The prerequisite for that end goal remains the same: initiating comprehensive peace talks where Yemenis themselves can decide their future and the region’s role in it.

Elana DeLozier is a research fellow in The Washington Institute’s Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy.