- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3079

Seeing Red: Trade and Threats Shaping Gulf-Horn Relations

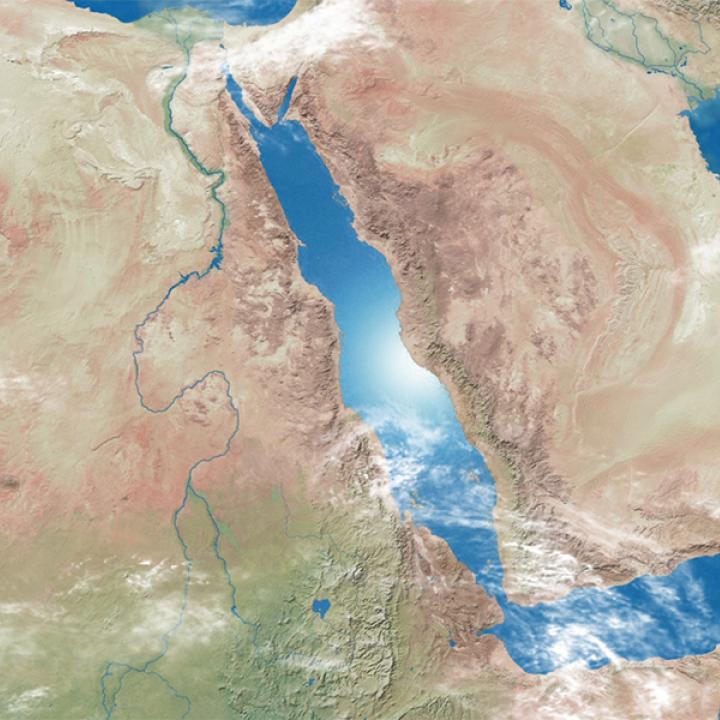

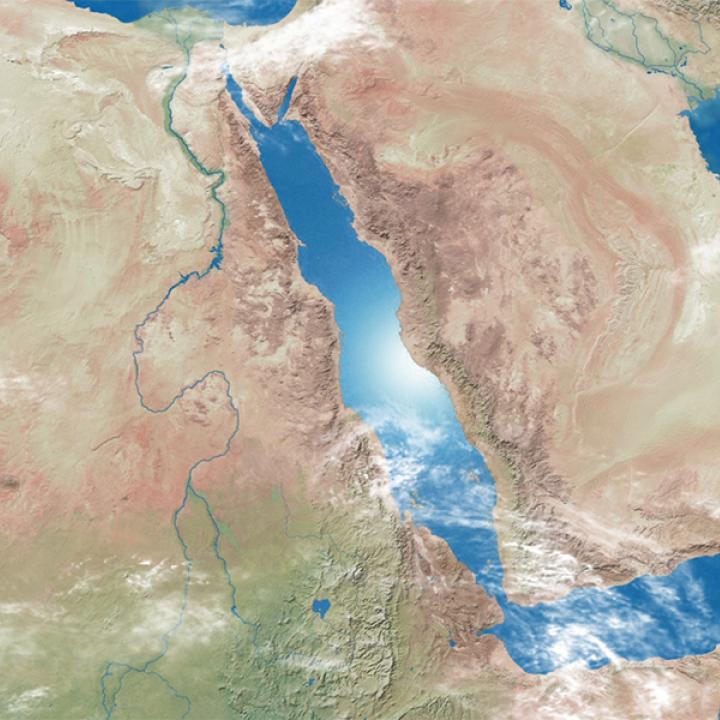

The Red Sea is fast becoming a critical economic and security node between the Gulf states and the Horn of Africa, so Washington should work to ensure cooperation, not conflict.

Alongside the perceived U.S. withdrawal from the Middle East, the emergence of new economic opportunities and security threats in the Red Sea has apparently spurred Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to draw closer to their neighbors in the Horn of Africa. This underdeveloped, populous area represents a clear economic opportunity for the Gulf, while the African states welcome the financial and infrastructure investment. Ideally, all nine states along the Red Sea—Somalia, Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen—would benefit from cooperation and coordination, but conflicts between regional players risk further destabilizing some of the more fragile states that flank the waterway. The United States should increase its diplomatic efforts to facilitate cooperation, stave off conflict, and support its allies in the area.

RED HOT: THE SCRAMBLE FOR FOOTHOLDS

As a major transit waterway for world trade, the Red Sea has long caught the attention of great powers. It is bounded in the north by the Suez Canal and the south by the Bab al-Mandab Strait, two critical chokepoints that the littoral states rely on to export oil or otherwise access global markets. It is also a core part of China’s “One Belt One Road” initiative, an ambitious plan to build a twenty-first-century equivalent of the lucrative Silk Road.

As a result, great powers and aspirant powers alike have increasingly been setting up camp in the Red Sea region. The United States established a military base in Djibouti in 2001 that also hosts British troops. Other countries also have bases: France (whose base also hosts German and Spanish forces), Italy, Japan, and China (which has also established a trade port there). Saudi Arabia has engaged in talks for a potential base in Djibouti as well, while Russia has done the same with Sudan. In addition, Turkey has a training base and port agreement with Somalia; Sudan has signed deals with both Ankara and Qatar to develop a port; and the UAE has varying degrees of access to at least eight ports or bases along the Red Sea, according to a January report by the Brookings Institution. As a senior African security official stated during the author’s recent trip to the Horn, “We have all five vetoes on our doorstep,” referring to the permanent members of the UN Security Council.

RED ALERT: PIRACY, THE YEMEN WAR, AND OTHER THREATS

Such a strong outside presence suggests that security will remain a key priority in the area. Regional officials and observers remember all too well that Egypt’s closure of the Straits of Tiran in the northern Red Sea helped spark the Six Day War in 1967. These longstanding security concerns—coupled with newer threats related to piracy, the Yemen war, and fears of U.S. withdrawal—appear to have boosted Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s interest in protecting their western flank.

In 2009, NATO initiated antipiracy missions in and around the Red Sea, continuing the campaign until 2016. Yet just as the piracy threat wound down, the Iranian-backed Houthi rebel group in Yemen began to demonstrate sophisticated coastal defense and sea denial capabilities, including antishipping missiles, sea mines, and self-guiding explosive boats. This forced Saudi Arabia to temporarily halt its shipments in the Red Sea in mid-2018. Meanwhile, Iran has long used the Red Sea to send weapons to armed groups, reportedly stationed a cargo ship off Yemen’s coast for intelligence purposes, and previously threatened to close transit chokepoints.

To stem these threats, Saudi Arabia spearheaded a new Red Sea collective in December, then organized last month’s Red Wave 1 naval exercises involving seven of the nine littoral states. The drills did not include Eritrea or Israel. Eritrea apparently declined an invitation but is expected to join in the future, though its preference for bilateral over multilateral relations may keep it on the sidelines a bit longer. Israel is unlikely to be officially invited, but it may quietly coordinate with some of the coastal states. Rumors of Ethiopian or Emirati participation also abound; although neither state borders the Red Sea, Ethiopia drives a great deal of trade through the waterway, and the UAE has a significant port presence there. The United States should play a greater role in greasing the wheels of some of these relationships, especially with Israel.

RED HERRING: AFRICAN ECONOMIC GAINS VS. WORRIES

The Red Sea’s economic potential is another driver of Gulf ambitions there. For example, the UAE has expanded its access to local ports in anticipation of future preferred trade routes, emphasizing its proven ability to manage complex logistics at such facilities. In the past, the Emiratis have sought to position Dubai as the middleman between Asia, Africa, and Europe, but the future of trade may be along China’s emerging “belt and road,” a more-or-less circular global route over land and sea. In this scenario, the Horn of Africa would play the middleman role, not Dubai, so access to Red Sea ports may help the UAE remain pivotal in world trade. As part of this strategy, the Emiratis plan to invest in infrastructure in Ethiopia, Somaliland, and Puntland, among other areas. They are also contenders to help reconstruct ports in Yemen once the war ends.

As mentioned previously, China, Qatar, Turkey, and other players have made investments of their own in the Horn, but African officials remain cautious. They worry about Beijing’s perceived blackmailing tactics, and what one official called the Gulf’s “ATM diplomacy.” They are also concerned about being drawn into external disputes such as the ongoing feud between Qatar and the Saudi-UAE bloc, or overt competition between China and the United States.

They find the Gulf dispute particularly worrisome. To be sure, African officials and observers acknowledge the value of Gulf support in spurring Ethiopia, Sudan, and Djibouti to pursue rapprochement with Eritrea. They also appreciate Gulf investment. Yet for most of them, the main priority is ensuring that the Gulf rift or other external matters do not play out on their turf.

Somalia is the most clear-cut example of this problem; since the Gulf rift began, Qatar has supported the Somali central government, while the UAE has supported the autonomous regions in the north. Observers worry that such policies will fracture or destabilize African countries already fragile from local rivalries. Riyadh did not help its case when a senior Saudi official stated in December that the kingdom’s goal in the Red Sea was to ensure “less negative outside influence,” a comment that many read as a jab at Qatar, Turkey, Iran, or all three. In short, the African states are loath to be the rope in regional games of tug of war, despite the potential economic gains.

RED TAPE: U.S. BUREAUCRACY NEEDS TO ADAPT

The U.S. government has a key role to play in addressing the Red Sea area’s growing importance, but to be effective, it will need to shift toward managing the diplomatic and military “seam” that runs down the region. Working across this seam is nothing new for U.S. officials; for example, Near East and Europe bureaus are accustomed to coordinating on Turkey, while CENTCOM often has to coordinate with AFRICOM, which oversees the base in Djibouti.

Yet some foreign service personnel have expressed concern that the two sides of the seam have not yet adapted to the changes occurring along the Red Sea. America’s partners are certainly doing so: Saudi Arabia appointed a minister of state for African affairs in early 2018, and the European Union has a special representative to the Horn of Africa. The United States should consider taking similar steps—perhaps appointing a special envoy or creating an interagency working group dedicated to the Red Sea. Either entity’s role would need to be comprehensive, pulling together the concerns of the State Department’s Near East desk, Africa desk, and China desk, along with the Defense Department, National Security Council, and other agencies.

To avoid creating a stir, Washington should discuss any such role with its Red Sea partners before making public announcements. And it should do so sooner rather than later. The area is fast becoming a critical node that pulls together far-flung portfolios, from economics and security to environmental, migration, and tourism factors. Someone needs to have their finger on that fast-beating pulse.

Elana DeLozier is a research fellow in The Washington Institute’s Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy.