The district’s ethnic composition and wartime migrations make it the weakest point of the YPG defense system, and the most likely entryway for Turkish troops and their proxies.

As Ankara reportedly prepares for a major incursion into northeast Syria, the border district of Tal Abyad may well be the Turkish army’s main target—and an easy one at that. The U.S. presence is weaker in Tal Abyad than in Kobane, and apparently due for imminent withdrawal. The district’s Arab-majority population rejects the People’s Defense Units (YPG), the U.S.-backed Kurdish force currently in control of the area. And unlike in Manbij and other points to the west, there is no risk of the Syrian army contesting control in Tal Abyad anytime soon.

If Turkish forces do in fact take the district, they will have a direct route of advance to Ayn Issa, whose capture would allow them to cut the main bloc of Kurdish-held territory in two: the Kobane and Manbij zones to the west, and the Qamishli and Hasaka zones to the east. This thrust would likely presage a larger offensive throughout all of northeast Syria, and the Kurds would be on their own in that fight. Given ethnic realities and wartime trends, the Arab militias in the YPG-led Syrian Defense Forces coalition are no doubt unwilling to help the Kurds stop the Turkish army and its local proxies. To the contrary, they could use this opportunity to break with the YPG and its unsustainable domination of Arab-majority areas.

ETHNIC SETTLEMENT AND DISPLACEMENT

France founded Tal Abyad in 1920 to control the Turkish border, and its first inhabitants were Armenians fleeing Turkish violence. The Baggara tribe, originally from Deir al-Zour, were the town’s first Arab inhabitants because they arrived as members of the French Levant army, then decided to stay. Irrigation advancements encouraged settlement in the surrounding countryside after World War II, with wheat and cotton cultivation becoming the area’s main resources. Smuggling with Turkey became a lucrative activity as well.

Today, several different tribes live in Tal Abyad town, each in its specific area. The Kurdish minority has its own neighborhood as well, in the western part of town. Mixed Arab-Kurdish weddings are rare—the two communities have lived separately for many years, and the gap between them has only widened during the current war.

In administrative terms, Tal Abyad district no longer belongs to the Syrian government province of Raqqa, but to the Kurdish canton of Kobane. Although the population is predominantly Arab, there is no civil council to represent them as in Manbij, Deir al-Zour, Raqqa, and other Arab-majority locales liberated by Kurdish forces. Instead, the YPG’s goal is to fully integrate Tal Abyad into Kurdish territory, which the group still envisions as an autonomous belt along most of the northern border.

In October 2015, Amnesty International accused the YPG of conducting an ethnic cleansing campaign against Arabs because some villages were reported to be deserted. Kurdish authorities responded that the residents had fled because they were Islamic State (IS) supporters who feared reprisals once the terrorist organization was forced out of the area. Whether or not that claim was true in these particular villages, many Arabs who backed IS did in fact flee Tal Abyad for that reason.

Click on maps for higher-resolution versions.

Moreover, some Arabs living under the YPG’s jurisdiction have complained about local Kurdification efforts, include property confiscation and exclusionary school curricula. Relations between Kurds and Arabs have been souring since 2012 due to abuses on both sides, including the expulsion of Kurds during the 2014 IS takeover.

TALLYING THE KURDISH MINORITY

In 2011, Tal Abyad town had 20,000 inhabitants, and the district 120,000—a density of fewer than 10 people per square kilometer. The population was concentrated on the border, where rainfall allows agriculture. Both the town and the countryside were roughly 70 percent Arab, 25 percent Kurdish, and 5% Turkmen, along with some Armenians.

A considerable demographic change took place during the war, however. Half the town’s population left due to the IS takeover and other threats; later, large numbers of internally displaced persons from Raqqa arrived. Tal Abyad had doubled its population by fall 2017, but most of the IDPs returned to Raqqa within a year once the IS “capital” began to recover from its hard-fought liberation. Although the Arab population of Tal Abyad is still larger than it was prewar, the local economic situation is not very attractive, and the YPG discourages Arabs from staying by imposing tougher conscription policies than it does in other areas.

MOST ARAB TRIBES OPPOSE THE YPG

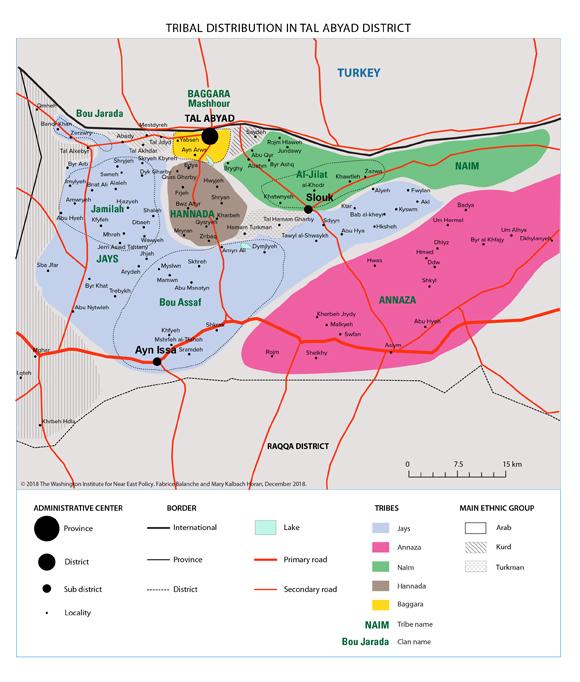

The Kurds no longer pay much heed to traditional tribal structures, but the tribal system still dominates Arab society in Tal Abyad. Long protected by Syria’s Baath regime, Arab tribal leaders have retained their status as notables and their capacity for political mobilization. The main tribe in Tal Abyad district is the Jays, divided into three powerful clans: the Bou Assaf, who are close to the YPG, and the Jamilah and Bou Jarada, who are very anti-YPG. Less prominent local tribes are the Naim, Hannada, Baggara, and Annaza. Two Turkmen collectives, the Slouk and Hamam Turkmen, also constitute tribes.

The Jays is a warrior tribe with strong ties to Turkey and a history of conflict with the Kurds of Kobane, whose agricultural lands are nearby. Before the war, the tribe was close to the Assad regime; once government forces withdrew in July 2012, it tried to behave like the master of the region. After periods of chaos and rebel takeover, the YPG occupied Tal Abyad city for a few days in March 2013, spurring some of the clans from Jays and other Arab tribes to ask for help from al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra (which including IS cadres at the time). In addition to pushing the YPG out of the district, this Arab alliance displaced the entire Kurdish population, destroying their homes in the process.

Later, once IS began its takeover in east Syria, the clans within Jays took different paths: the Jamilah and Bou Jarada supported the organization, while the Bou Assaf helped create the rebel group Liwa Thuwar al-Raqqa (Raqqa Revolutionaries Brigade) and participated in liberating Tal Abyad from IS forces in 2015 (its name eventually changed to Jabhat Thuwar al-Raqqa). Likewise, members of the Naim, Baggara, and Annaza tribes took part in the liberation of Raqqa under the banner of Liwa Suqur al-Raqqa (Raqqa Hawks Brigade). Yet several prominent tribal militia leaders defected to the Assad regime in 2017, and the loyalty of those who remain with the Syrian Defense Forces is dubious.

The Hannada tribe remained largely neutral during these conflicts. This puts it in a good position to resolve problems between other tribes, with Hannada member Aissa Ibrahim currently serving as chief of the Tal Abyad Reconciliation Committee. This September, however, a conscription operation by the Kurdish security force Asayesh went badly in the Hannada rural stronghold of Khaldya. About fifty men were arrested amid local protests, and one of them died while being transferred to Tal Abyad. This pushed the whole tribe into opposition against the YPG. The Kurds have also kept a tight grip on local Turkmen communities, since they supported IS and have a natural affinity with Turkey.

Currently, Arab refugees from Tal Abyad are keen to return to the district by force with Turkey’s help. Many of them have trained in Turkish military camps in Sanliurfa and Akcakale, the border town nearest Tal Abyad. These young trainees may be used as the vanguard to “liberate” the district, similar to how the Turkish army used proxies when invading the Kurdish district of Afrin in northwest Syria. This strategy has an even better chance of succeeding (and avoiding international outcry) in Tal Abyad because the majority of the population is Arab, unlike in Afrin where Kurds are more numerous. For instance, the Sukhanya clan fled Tal Abyad in May 2015 and sought refuge in Turkey, and their homes have since been confiscated by the YPG. Today, they regularly demonstrate on the Turkish side of the border to demand the YPG’s departure, and their militia is ready to participate in any advance against the town.

Fabrice Balanche is an assistant professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, and author of the 2018 Washington Institute monograph Sectarianism in Syria's Civil War: A Geopolitical Study.