From dissolving the group’s caliphate to killing its leader, the coalition has notched major achievements, but all that work may be for naught if the United States and other members do not renew their cooperation at the upcoming ministerial meeting.

After Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was killed on October 27, one might wonder why foreign officials are still gathering in Washington on November 14 for a meeting of the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. But the threat posed by the group has persisted through years of similar setbacks, so the many countries active in countering ISIS must discuss how best to continue their efforts.

When officials held their previous “D-ISIS” meeting in Paris this June, they concluded that “taking into account the uncertain security situation on the ground, it is particularly important that Coalition military forces remain in the Levant to provide the necessary support to our partners on the ground.” This commitment is now being severely tested by Washington’s decision to remove troops and essentially abandon the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Next week’s meeting will further test U.S. leadership on preserving the coalition framework, which is essential to coordinating actions beyond the military level and continuing the march toward long-term victory against ISIS.

WHAT THE COALITION HAS ACHIEVED MILITARILY

The coalition was created in September 2014 in response to the Islamic State’s conquest of large swaths of Syrian and Iraqi territory. Since then, it has been the primary framework through which eighty-one countries have coordinated their military and civilian efforts to address the threat.

The coalition’s primary local allies in this fight have been Kurdish peshmerga and federal troops in Iraq, and Kurdish and Arab SDF troops in northeast Syria. The United States has provided the most substantial support to these troops through a small but effective counterterrorism operation. Numerous allies have contributed to this effort via intelligence collection, airstrikes, equipment provision, and military training, including Australia, Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Jordan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

Despite a difficult campaign with many casualties, local troops managed to retake all ISIS territories by March 2019. Steady cooperation with these forces also enabled the recent U.S. operation to kill Baghdadi.

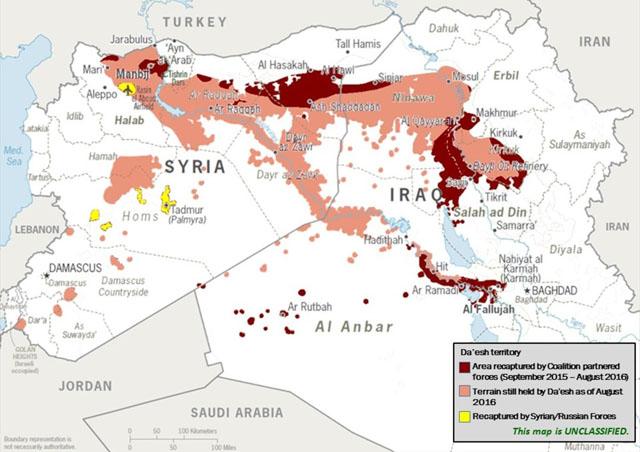

U.S. Defense Department map showing ISIS territory at its peak in 2015, and how coalition activities shrank it significantly in the first year of operations.

NONMILITARY LINES OF EFFORT

Although only a limited number of countries have participated militarily, the coalition has been an effective mechanism for all eighty-one members to cooperate on other crucial efforts such as countering jihadist ideology and terrorist financing, stabilizing former ISIS territories, impeding the flow of ISIS fighters, and prosecuting returnees.

Since 2017, European contributions under the coalition framework have totaled more than $400 million in support to northeast Syria. These funds have contributed to clearing land mines left by ISIS, averting humanitarian crises in refugee camps, repairing basic infrastructure, providing primary healthcare, and relaunching the local economy. The coalition has also promoted bilateral and multilateral support to Iraq, including funds to rebuild the University of Mosul. Such efforts are crucial to restoring decent living conditions for populations who suffered from ISIS rule and the war against it. In addition, the coalition has coordinated projects to counter ISIS propaganda and shut down its social network accounts. Information sharing on terrorist financing and foreign fighters has been improved as well.

In short, the coalition was formed to ensure the Islamic State’s enduring defeat, and increased cooperation on nonmilitary dimensions is required to achieve this goal. That is why the alliance still has an important role to play.

KEY ISSUES FOR THE UPCOMING MEETING

Items on the agenda for next week’s small-group ministerial meeting include several burning political issues:

How to deal with the new Syria map? The most contentious issue is the instability caused by last month’s Turkish incursion and uncoordinated U.S. withdrawal in northeast Syria. French foreign minister Jean-Yves Le Drian requested the ministerial meeting after coalition member Turkey launched its operation to retake a thirty-kilometer-deep zone along the border.

Partner countries will have to discuss the consequences of this changing map now that Turkish, Russian, and Syrian regime forces are replacing the U.S. presence in the northeast. President Trump has stated his desire to retain control of oil fields in east Syria, but it is not clear where and how Washington plans to continue its anti-ISIS operations. Without its recently abandoned bases in Syria, the coalition would likely have to rely on Erbil, Iraq, as its main logistical base, but this would require extensive engagement with the Kurdistan Regional Government and Baghdad.

In any case, the new situation is harming some of the coalition’s efforts, and will likely lead the U.S. delegation to ask other partners to increase their contributions and deployments. Yet while countries such as Britain, France, and Germany offered to do more in past months following President Trump’s December 2018 statement supporting troop withdrawal, European contributions to counterterrorism operations against regional ISIS cells will be difficult without a U.S. presence. Similarly, European NGOs cannot operate locally without U.S. security guarantees. Even U.S. targeting of terrorists might become more difficult in the current operating environment.

How to deal with ISIS detainees? The coalition’s most urgent task is designing a coordinated response to the detention and prosecution of ISIS detainees. In the immediate term, this means preventing ISIS prison breaks within Syria’s current security vacuum.

Accordingly, U.S. officials who attend next week’s meeting will likely be asked to explain how the SDF can be expected to continue detaining ISIS fighters while contending with the U.S. departure and Turkish-Syrian military advances. On October 15, Turkish presidential spokesman Fahrettin Altun declared that “nobody is dumping those [imprisoned] terrorists on Turkey,” so it is unclear whether a new division of labor with Ankara will be possible.

Thus far, President Trump has demanded that European countries repatriate and prosecute their citizens who joined ISIS, going so far as to threaten their potential release. In the words of one unnamed security official, European governments want to avoid creating “a new Guantanamo Bay” in Syria, but they are even more wary of the potential dangers involved in repatriation.

Among the estimated 11,000 ISIS detainees in northeast Syria, some 2,000 are foreign fighters, according to an October 25 policy brief issued by the European Council on Foreign Relations. The same source noted that only around 200 of these fighters are European, but they still pose a major threat in terms of future terrorist attacks on the continent.

The majority of the foreign fighters come from other Arab countries, where local institutions would struggle to handle them without international support. Consider the large number of Tunisian fighters, whose return home en masse could replicate Algeria’s experience three decades ago, when returning Afghanistan veterans played a key role in the country’s civil war.

Indeed, while some experts call for repatriation of detainees by each home country, logistical obstacles and potential legal shortcomings would complicate this proposal (e.g., the difficulty of gathering evidence for trial). There is no easy option for prosecuting these fighters, and other practical issues are a work in progress, such as developing reintegration programs for deeply radicalized and sometimes violent individuals who have served their sentence. Furthermore, European publics largely oppose repatriation.

Yet dealing with the foreign fighters is actually the smaller half of the problem. Most of the 11,000 detained fighters are Syrians and Iraqis who could rebuild ISIS in both countries if left to their own devices, much like al-Qaeda in Iraq went underground in 2007-2009 before reemerging as ISIS in 2011.

Since the fate of detained fighters is an international issue that affects some fifty-four countries to various degrees, another option is to prosecute them through an ad hoc international jurisdiction, similar to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Yet experts argue that setting up such a tribunal may take too much time and would likely be opposed by key states. For instance, Russia seems intent on pushing the Syrian regime to take control of the detention camps, potentially using ISIS foreign fighters as bargaining chips with the West.

A TEST OF U.S. LEADERSHIP

Beyond discussing specific solutions, the meeting will serve as a test of U.S. leadership over international counterterrorism efforts. Credibility requires stability—in the wake of Washington’s hasty Syria withdrawal, it will be very difficult for senior U.S. officials to convince Western and Middle Eastern partners that any proposals they make next week will not suddenly change the week after. Allies may therefore be unwilling to send troops or make other investments that are contingent on U.S. policy remaining constant. More likely, they will try to adapt to the reality of Russia’s strengthened position on the ground in Syria and its growing influence in the Middle East theater.

To be sure, the Trump administration’s focus on burden sharing suggests that the counter-ISIS coalition still has a vital role to play. Most important, the coalition provides the framework for technical and political discussions, especially with Arab and Turkish officials, who will likely be central to addressing the threat posed by thousands of ISIS detainees. The key question, however, is whether the administration wants to keep working through multinational alliances or invest more in bilateral relationships instead.

Here, the success of the coalition’s nonmilitary lines of effort offers a lesson on the necessity of multilateral counterterrorism cooperation, including at the strategic level. The underlying conditions that led to the rise of ISIS—poor governance, corruption, repression—persist across the Middle East, and political settlements are still needed in Syria and Iraq. These tough challenges require the United States and its allies to engage diplomatically at all levels, such as by pressuring the Syrian regime and the UN-led Constitutional Committee with Turkey’s help. In Iraq, the coalition should capitalize on the current climate of anti-government protests to advocate for more-inclusive governance in former ISIS territories. Some have also suggested expanding the coalition to counter the terrorist and insurgent threat posed by ISIS wilayat (provinces), which have sprouted in Afghanistan, Algeria, Cameroon, Chad, Chechnya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, India, Libya, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Turkey, and Yemen.

The Trump administration’s 2018 national counterterrorism strategy spoke directly to the benefit of such wide-ranging partnerships: “Our increasingly interconnected world demands that we prioritize the partnerships that will lead to both actions and enduring efforts that diminish terrorism. The United States will, therefore, partner with governments and organizations,...the technology sector, financial institutions, and civil society.” In this vein, the counter-ISIS coalition is needed as much today as it was prior to the terrorist group’s latest setbacks.

Matthew Levitt is The Washington Institute's Fromer-Wexler Fellow and director of its Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence.