Tehran and its proxies have been exerting hard and soft power in northeast Syria, combining military consolidation with economic, social, and religious outreach in order to cement their long-term influence.

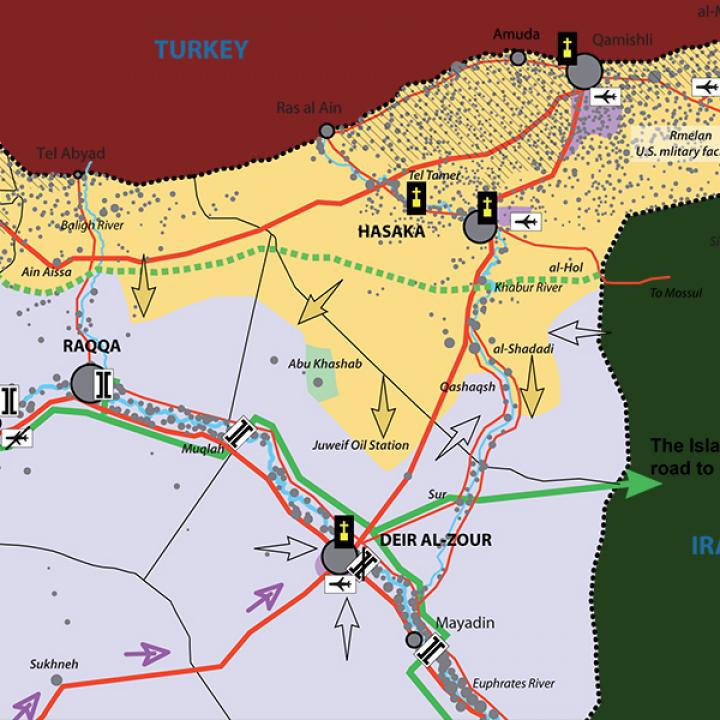

On September 30, Syria and Iraq reopened their main border crossing between al-Bukamal and al-Qaim, which had been formally closed for five years. The circumstances surrounding the event were telling—the ceremony was delayed by a couple weeks because of unclaimed foreign airstrikes on Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps targets in east Syria following the Iranian attack against Saudi oil facilities earlier that month. What exactly have the IRGC and its local proxies been doing in Deir al-Zour province? And what does this activity tell us about Iran’s wider plans there?

OPENING THE DOOR FOR IRAQI PROXIES

The border ceremony was led by Khadhim al-Ikabi, an Iraqi government representative, raising questions about whether the decision will help circumvent U.S. sanctions placed on Iran. Although Syrian state media celebrated the event as an opportunity to increase trade with Iraq, Tehran’s reaction indicated that the crossing will mainly serve Iranian military interests.

According to officials and media in Iran, reopening the border is of “high strategic importance” in strengthening the Islamic Republic’s “trilateral coalition” with Baghdad and Damascus. As a recent article in Mehr News opined, the event may also be a “prelude” for Iran to confront the potentially shrinking U.S. military presence in northeast Syria by letting “al-Hashd al-Shabi and other groups fully enter Syrian territory and eradicate terrorism,” referring in part to Shia militias within Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces that often operate across the border.

MARGINALIZING ASSAD’S FORCES

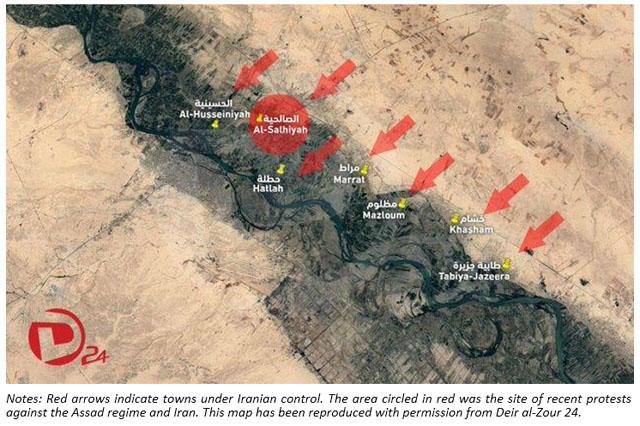

According to Syrian anti-regime activists, Iran and its proxies currently control at least seven towns on the east side of the Euphrates River stretching south of Deir al-Zour city, from Mayadin to al-Bukamal. This includes full military authority and executive administration exerted by nearly 4,500 armed personnel, some from the IRGC, others from Shia militias such as the Baqir Brigade, Fatemiyoun Brigade, al-Hashd al-Shabi, and the various groups that call themselves “Syrian Hezbollah” (Hezbollah fi Suriya).

Their presence has significantly weakened the local role of the Assad regime’s National Defense Force militias, partly due to the IRGC’s lack of faith in the NDF’s capabilities, but also because of Tehran’s long-term plan to consolidate its own influence. According to Omar Abu Layla, head of the Deir al-Zour 24 news network, the NDF is “only allowed” to exercise control over civilian areas in the province; it is not allowed to participate in battle. In some cases, the IRGC has reportedly arrested NDF fighters due to internal power struggles. Even the presence of Russian military units has apparently been minimized throughout the province.

Meanwhile, Iran is building two new military bases in the area: one in the western suburbs of Mayadin, and a larger one in al-Bukamal called “Imam Ali.” Both are being constructed in cooperation with Jihad al-Binaa and the Imam Hussein Organization, two Iranian-sponsored foundations that have branches in Deir al-Zour city, Mayadin, and al-Bukamal. These facilities will further Tehran’s goal of controlling a key strategic route: from al-Bukamal north to the T2 oil pumping station in Mayadin; then west to Tiyas, home to the T-4 pumping station/Syrian air base; and finally to Lebanon’s Beqa Valley, Hezbollah’s main stronghold. Various foreign actors have conducted airstrikes along portions of this route, but IRGC and proxy forces have reduced their exposure to such operations by hiding inside civilian homes.

PAYING AND HOUSING FIGHTERS

Although the Shia militias in Deir al-Zour include Afghan and Pakistani factions, Iraq’s al-Hashd al-Shabi serve as Iran’s main financial conduit in the province, particularly in al-Bukamal. The salaries and distribution methods involved differ depending on a recruit’s nationality. For instance, Iraqi fighters in Syria receive around $400 per month on Mastercards given to them by al-Hashd al-Shabi. Other nationalities receive their money in cash in person, often withdrawn from PMF-managed banks in Iraq—a potential violation of U.S. sanctions policy.

As for local Syrian recruits, they are paid directly by the IRGC in amounts that depend on their individual duties. Those who serve in their hometowns receive $100 per month, while those who travel to the frontlines receive $150 along with military vehicles, fuel vouchers, and miscellaneous spending money. According to local anti-regime figures, these well-organized IRGC financial practices are far superior to the Assad regime’s “chaotic and bankrupt” security structure. Similar to what happened when the Islamic State controlled the area, the IRGC’s financial incentives are attracting unemployed, impoverished Syrian men as well as foreign fighters.

In addition, Shia recruits and their families are guaranteed housing in properties bought and managed by Iranian businessmen. As of November 2018, over one hundred foreign Shia families had settled in the southern neighborhoods of Mayadin, and a similar number of Iraqi Shia families had settled in al-Bukamal; these figures have surely grown since then.

FUNDING EDUCATIONAL AND RELIGIOUS INDOCTRINATION

Iranian reconstruction initiatives and public works projects in Syria have become increasingly overt. Besides giving direct payouts to Shia recruits, the IRGC and al-Hashd al-Shabi are infiltrating the social fabric of the majority Sunni Arab population through a variety of social and economic activities, helping them impose their brand of Twelver Shia Islam on cash-strapped locals.

For example, with the Assad regime’s blessing, the Iranian Cultural Center in Deir al-Zour city essentially forces school and university students to participate in its events. The regime’s Baath Party Revolutionary Youth Union has ordered the local education directorate to lead field trips to Shia religious ceremonies, IRGC lectures, short-story writing events, and sports competitions; in return, students earn extra credit and financial aid.

Similarly, study-abroad scholarships are heavily advertised and targeted at students who are interested in pursuing religious studies and returning to Syria as Twelver Shia missionaries. The scholarships are open to age groups ranging from elementary school children to students in their thirties. Nearly a hundred students from Deir al-Zour have already traveled to Iran for this program (the younger ones accompanied by their guardians). In addition, Iranian teachers run three schools in Mayadin, al-Bukamal, and Deir al-Zour city, offering Persian language and history classes alongside other subjects; enrollment is reportedly around two hundred students.

Some local tribes in Deir al-Zour play a major role in enforcing this Iranian agenda. In areas such as Sabikhan and Mayadin, the IRGC has ordered tribal sheikhs to invite residents to events at Shia husseiniyeh (congregation halls), where prizes and aid are offered to orphans, women, and families of martyrs. Local sources also indicate that Sheikh Nawaf al-Bashir of the Baggara tribe runs an Iranian-backed militia in Mhaymidah. Likewise, a Baajin tribal official in Mayadin, Saleh Muhammad Ismail al-Baaj, is considered Tehran’s main ally in spreading Twelver Shia Islam in cooperation with the Iranian Cultural Center in Damascus. This is in addition to his role as a religious advisor to the Abu Fadl al-Abbas Brigade, a pro-Assad militia unit composed of Iraqi and Lebanese fighters.

The “stick” in this “carrot and stick” approach has become clear as well. Last year, for example, Syrian authorities arrested twenty Sunni imams from Sabikhan, Mayadin, al-Bukamal, and other towns for refusing to perform the Shia-style call to prayer. In contrast, imams who agreed to the order received a wage increase.

Deir al-Zour’s centrality to Iran’s religious and strategic goals was reinforced this past July, when IRGC-Qods Force commander Qasem Soleimani visited al-Bukamal in person. There, he met with militia leaders to establish a new unit under the name “Liwa Hurras al-Maqamat” (The Guardians of Holy Shrines Brigade), which will be charged with defending Shia shrines recently built in Deir al-Zour. By placing new Shia shrines on or near older holy sites previously established by Sunni dynasties, the IRGC seeks to manufacture local religious legitimacy. This mission will align well with the numerous humanitarian organizations Iran has established in the province, which introduce locals to Shia tenets while distributing aid to them.

U.S. SHOULD HARNESS LOCAL DISENCHANTMENT

Recently, the combination of these Iranian mechanisms has spurred citizens in Deir al-Zour province to launch protests railing against the Assad regime and criticizing the IRGC’s military presence and social influence. Such demonstrations represent a crucial opportunity for the United States and its regional allies to reverse troubling trends on the ground, whether by publicly stating support for demonstrators, shielding them from harm when possible, and/or helping them covertly. Doing so would not only support Syrians’ justifiable demands, but also hinder Iran’s goal of creating a “Shia crescent” through Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon—an outcome that would pose a major threat to American and allied interests in the Middle East. In addition, allies should step up their more forceful measures as necessary, from conducting further airstrikes against IRGC elements and designated Iranian proxies inside Syria, to preventing or discouraging Iraqi PMF institutions from transferring funds to fighters operating across the border.

Oula A. Alrifai is a fellow in The Washington Institute’s Geduld Program on Arab Politics.