- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3636

What Zawahiri’s Death Means for al-Qaeda and Its Branches

Despite the potent symbolic benefits of taking out the infamous terrorist ideologue, his death is unlikely to affect the organization’s daily operations, which are increasingly being driven by dangerous affiliates in Africa.

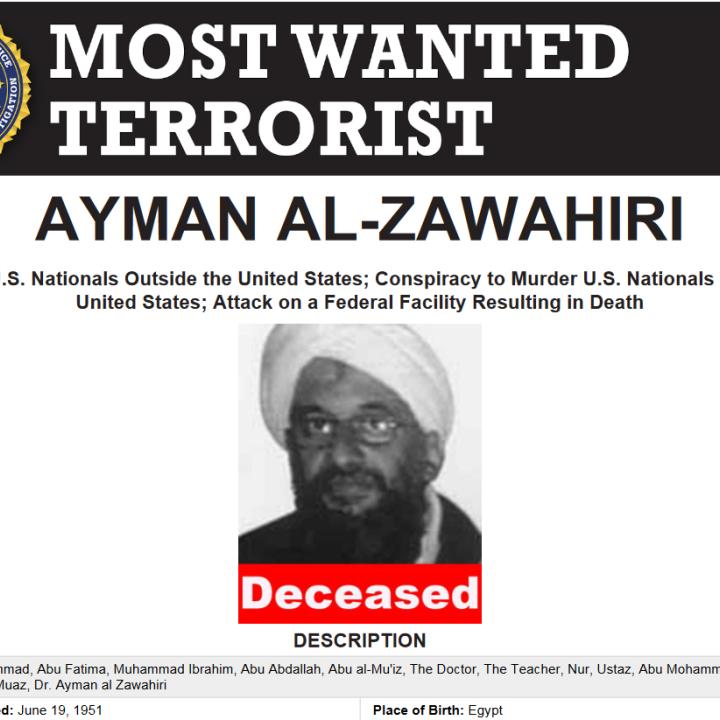

Ayman al-Zawahiri, the longtime deputy leader of al-Qaeda (AQ) who took over the organization after Osama bin Laden’s death in 2011, was killed by a U.S. drone strike in Afghanistan on July 31. When President Biden announced the news, he underscored that Washington will bring such adversaries to justice no matter how long it takes.

Zawahiri’s death portends a new era for AQ, one less certain in its senior leadership. Unlike his predecessor, he was not known for inspirational rhetoric or media savvy, showing a preference for long, boring treatises and videotaped sermons that led many to see him as a less formidable terrorist leader than bin Laden. Yet Zawahiri undeniably provided much of the intellectual foundation for AQ’s international agenda of committing mass-casualty terrorist attacks and promoting jihadist governance. Today, some of the organization’s branches, especially in Somalia and Mali, are in strong positions to continue this mission.

Terrorist Ideologue

Born to a wealthy, prestigious Egyptian family and working as a physician in his early life, Zawahiri founded Egyptian Islamic Jihad in the 1970s, a terrorist group dedicated to overthrowing the regime in Cairo. By the late 1980s, his dwindling group began working more closely with AQ, which was concluding the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan at the time. In addition to a penchant for indiscriminate attacks that killed civilians, his main contribution was the strategic mindset of targeting the “far enemy” in order to facilitate the overthrow of the “near enemy.” That is, by attacking the United States and other actors who supported what he perceived to be pro-Western, insufficiently Islamic regimes in the Arab and Muslim worlds, the movement could eventually unseat those “apostate” regimes.

In a so-called fatwa issued in February 1998 under the name of the “World Islamic Front,” bin Laden and Zawahiri declared that murdering Americans was the “individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible.” Their two groups would formally merge in June 2001, a few months before the 9/11 attacks.

A few weeks after those attacks, Zawahiri released “Knights Under the Prophet’s Banner,” a twelve-part essay serialized in the London-based newspaper Asharq al-Awsat. The screed laid out his vision of jihad as an ongoing struggle for survival between good and evil, with the West (led by the United States, Israel, and “apostate” Arab regimes) trying to destroy Islam. The solution, he posited, was for Muslims to embrace militant jihadism and strike at the perceived enemies of Islam. As an example, he cited the 1997 terrorist attack in Luxor, Egypt, in which al-Gamaa al-Islamiyah killed sixty-two people, mostly foreign tourists.

Passing the Tin Can

Beyond his sometimes esoteric sermonizing, Zawahiri often found himself dealing with the uncomfortable minutiae of running a large organization after bin Laden’s death, particularly fundraising. As AQ began to face financial hardship in the years after 9/11, it was Zawahiri who would typically be sent out with a tin can.

For example, in a July 2005 letter to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the upstart leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, Zawahiri humbly asked for “approximately one hundred thousand dollars” because “many of the lines have been cut off.” And in 2008, he could be heard in a recorded message distributed via cell phones in Saudi Arabia requesting “donations for hundreds of the families of captives and martyrs in Pakistan and Afghanistan.” In response, Saudi authorities reportedly arrested fifty-six suspected AQ members who were using the recording to raise funds.

Zawahiri had previous experience acquiring and moving money, which appears to be what he was doing when Russian authorities arrested him in late 1996 as he tried to enter Chechnya. (Unaware of who he was, they soon released him.) That same decade, he reportedly raised funds in California mosques for Islamic charities purportedly supporting Afghan refugees.

The Syrian Jihad Brings Promise, Then Peril

Syria’s civil war provided a new arena where Zawahiri could show his relevance following bin Laden’s death. Early on, intervening in the conflict appeared to bear fruit, with Syrian branch Jabhat al-Nusra becoming the strongest AQ affiliate in the world after spurning entreaties from rival jihadist organization the Islamic State (IS).

Keen to stay atop the movement and compete with IS, Zawahiri dispatched senior AQ veterans from Afghanistan and Pakistan to set up a terrorist network in Syria between 2012 and 2015, with the explicit purpose of carrying out attacks abroad. The network was dubbed the “Khorasan Group” by U.S. counterterrorism officials, who revealed in September 2014 that they were tracking “imminent plots” by Khorasan operatives “to conduct attacks in the United States or Europe.”

AQ’s fortunes in Syria changed over the next few years, however, as U.S. airstrikes killed many of the network’s leaders and dwindled the ranks of AQ veterans whose experience stretched back to Afghanistan in the 1980s. Today, neither the Khorasan Group nor its successor, Huras al-Din, are actively operating in Syria. For its part, Jabhat al-Nusra broke from AQ in 2016, then merged with other groups and rebranded itself as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in 2017. Afterward, it began cracking down on rivals like Huras al-Din in earnest, more or less eliminating the AQ cell by June 2020.

In the end, the Syrian jihad undermined AQ’s position in the region, as defections to IS mounted and HTS began focusing more on local governance and fighting the Assad regime than global jihad. Although senior HTS figures Abu Mariyah al-Qahtani and Abdul Rahim Atun eulogized Zawahiri hours after he was killed, this was more a case of them showing respect to a fellow jihadist in the trenches than a sign that HTS might be coming home to AQ.

What Next for al-Qaeda and Its Branches?

Although Syria did not work out well for Zawahiri, all of AQ’s branches outside that theater remained loyal to him and the AQ cause even amid the spread of IS. To be sure, some of these branches—such as al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent—have faced severe challenges. Yet other branches—particularly in Somalia (al-Shabab) and Mali (Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin, or JNIM)—have major upside today and continue to lodge victories against local governments.

Regarding who will succeed Zawahiri, the UN’s most recent report on AQ noted that the leaders of al-Shabab and JNIM were potentially in line to take his place if he were to die. Yet moving AQ’s global leadership from its historical roots in the AfPak region to Africa would be unprecedented. Other potential candidates include two old guard AQ members: Saif al-Adel and Abd al-Rahman al-Maghrebi, Zawahiri’s son-in-law. Both of them are currently based in Iran, however, so naming either as the next AQ emir could create internal legitimacy issues.

Another possibility is promoting a young, charismatic, but relatively unknown leader with whom potential recruits could connect in a way Zawahiri never did. AQ continues to compete with IS for followers and recruits, so finding a dynamic new leader will likely be a priority.

At the end of the day, however, Zawahiri’s death is unlikely to have a significant impact on the operational capabilities of AQ or its branches. He was not believed to be running the organization’s daily affairs, only broad strategic decisionmaking. In many ways, AQ figures in the AfPak region have not “moved” the movement for a while. In the past decade, much of AQ’s relevance has been based on the fortunes of branches abroad, first in Yemen and Syria, and later in Somalia and Mali. Thus, regardless of who is chosen as the next leader, the movement’s future will be determined by battles far from the streets of Kabul where Zawahiri was killed. Questions will surely be asked about the stability of AQ’s core until a successor is named, but in the meantime the network’s most potent arms will keep threatening and destabilizing wide swaths of Africa.

As for Zawahiri’s leadership legacy, one cannot escape the fact that AQ has been steadily devolving from the unipolar leader of the global jihadist movement since he took over. Despite the major threat posed by certain affiliates abroad, AQ lost its two strongest branches in the heart of the Arab world under his watch—IS and HTS—and is now weaker on the world stage.

Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler Fellow and director of the Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at The Washington Institute. Aaron Y. Zelin is the Institute’s Richard Borow Fellow and founder of the website Jihadology.net.