- Policy Analysis

- Policy Notes 151

Anonymous Sources in Gaza War Reporting: The Washington Post vs. Its Peers

In such a challenging environment, news organizations must work especially hard to convince readers that sources are honest, legitimate, and trustworthy.

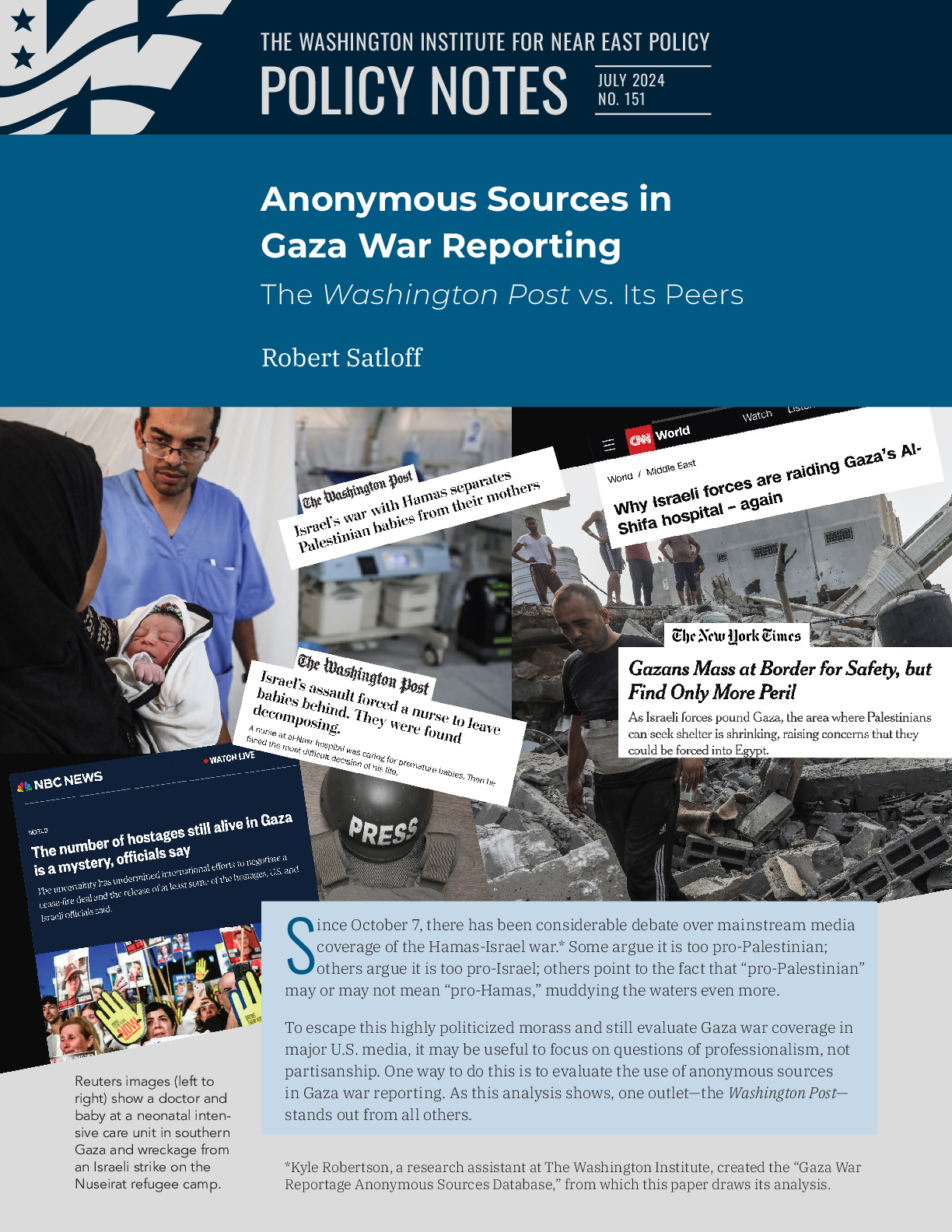

Since October 7, there has been considerable debate over mainstream media coverage of the Hamas-Israel war. Some argue it is too pro-Palestinian; others argue it is too pro-Israel; others point to the fact that “pro-Palestinian” may or may not mean “pro-Hamas,” muddying the waters even more.*

To escape this highly politicized morass and still evaluate Gaza war coverage in major U.S. media, it may be useful to focus on questions of professionalism, not partisanship. One way to do this is to evaluate the use of anonymous sources in Gaza war reporting. As this analysis shows, one outlet—the Washington Post—stands out from all others.

One of the most problematic aspects of covering the Hamas-Israel war is that Israel forbids the entry of foreign journalists into Gaza, except for those periodically embedded with Israeli troops. This leaves international news agencies relying either on the reporting of local Palestinian journalists or, alternatively, telephone or online reporting by their own staff located outside Gaza.

As a result, news organizations with few or no local staff face numerous difficulties in reporting the details of the conflict, but none is more serious than the problem of citing anonymous (or confidential) sources. Every media outlet has its own rules governing the use of such sources, but they share common principles. At the core, there are five:

- The use of unidentified sources should be rare, reserved for situations in which the news outlet could not otherwise publish information it considers newsworthy and reliable.

- The material from an anonymous source must be factual, vital to the story, and obtainable no other way.

- The material needs to be information and not opinion, observation, or speculation.

- Requests for anonymity should, at first, always be declined; a bona fide effort must be made to get the source on the record or, at a minimum, to confirm the information provided through other sources or independent reporting.

- Every use of an anonymous source should be approved by an editor or manager; when the use of such a source is the centerpiece (or lede) of an article, it needs to be approved by a senior editor.

Those rules apply in the best of circumstances, which Gaza certainly is not. The “confidence burden”—what is needed to convince readers that a source is honest, legitimate, and trustworthy—is substantially higher when a media platform lacks on-the-ground reporters to meet face-to-face with local sources to assess their veracity and confirm through independent means the information they provided. It stands to reason, therefore, that the use of anonymous sources by U.S. media reporting on the situation in Gaza should be exceedingly rare. (This is separate, one should note, from the granting of anonymity to government officials with specialized information connected to this conflict, be they American, Israeli, Palestinian, Arab, European, or those associated with the United Nations and its agencies.)

Therefore, to test the professionalism of major U.S. media covering the Gaza war, The Washington Institute created a database of all stories that included anonymous sourcing during the first six months of the conflict by seven leading U.S. media platforms—the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal, along with ABC News, CBS News, ABC News, and CNN. (For the television media, the Institute used published online stories, not transcripts of video segments.)

See the full “Gaza War Reportage Anonymous Sources Database.”

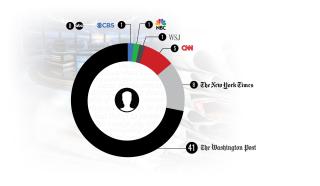

The database ultimately included 436 stories, but the vast majority—379—drew from an anonymous or confidential source who was a government or organizational official or someone described as being knowledgeable about sensitive political, military, or diplomatic issues. Separating those out left the database with just 57 stories that cited local people as anonymous sources. That is a laudably low number, especially when one considers the thousands of stories that have been printed on the Gaza war. But the breakdown among the seven news media tells its own story (see figure 1). Namely, the Washington Post was responsible for 72 percent of all the citations of Gaza-related unofficial anonymous sources—more than five times as many as both the New York Times (8) and all the other major U.S. media platforms combined (8).

A close look at those 41 stories offers insight into how the Post has reported the war. Specifically, more than half of the local Gaza-related nonofficial sources were granted anonymity to protect the source’s safety, security, or privacy—though in no case did the Post explain the nature of the threat, whether it came from Hamas, Israel, or some other party, or even if it met some verifiable threshold of validity.

In about a quarter of the cases, the Post gave anonymity to nongovernment sources—usually aid workers, medical technicians, or doctors—because they said they were not authorized to speak publicly or to the media, though it was quite rare for a citation to link a source to a particular institution. And some of the other explanations for granting anonymity were simply bizarre, such as one purporting to protect a “local charity worker” from being inundated with requests for assistance.

A detailed review of the Post’s Gaza coverage shows that more than 80 percent of the total were secondary subjects often providing a confirming quotation or color to complement observations from named sources. This use of anonymity is itself quite problematic, since it violates the “necessity” principle, by which media should restrict anonymous sourcing to cases when no other way to report essential information is available. As the Post’s own standards state, “We should avoid blind quotations whose only purpose is to add color to a story.” In practice, this means that few of these uses of anonymous sources should have been allowed into the newspaper.

Another problem with frequent use of anonymous sources identified only—for example—as a Gazan aid worker, medical technician, or local physician is that readers have no way of knowing whether the same person is being cited repeatedly. This is an especially serious problem in the Hamas-Israel conflict since reporters have no firsthand ability to cultivate new sources; in this scenario, a discerning reader’s presumption will be that journalists have to rely on people they already know. Repetitive use of similar-sounding anonymous sources only compounds the lack of trust readers will have that journalists are continually searching for new voices with something unique to offer, rather than the “usual suspects” to whom they return for quotes time and time again.

On five occasions, the anonymous source in the Post was the main subject of an article. According to the paper’s standards, that means use of the source had to be approved by a senior editor. Each of these stories was itself problematic:

- An October 13, 2023, story that opens with “Maha” describing why she, along with more than a million other Palestinians, evacuated Gaza City: “‘You can die anywhere here,’ Maha said in a phone interview, speaking on the condition that she be identified by only her first name to protect her safety. ‘But if they’re telling us to leave, that means they are going to be doing bad things to people.’” She was one of three unidentified sources cited in this article, along with two Palestinians who were named. With about one million evacuees, no explanation was offered for why Maha—and not someone named—had to be the source for this emotive quotation.

- A November 17, 2023, story, updated on December 28, alleging a purposeful Israeli policy of separating Gazan mothers from their premature babies allowed to be born in Israeli or West Bank hospitals.

- This article also the subject of a lengthy critique by the author alleging numerous violations of journalistic practice, which led to the Post re-reporting the story and issuing an apology and a correction.

- A December 3, 2023, story about a male nurse at al-Nasr Hospital in Gaza City forced to choose which of a handful of premature babies to save, with the rest allegedly left to die and decompose. This article was the subject of another lengthy critique by the author that alleges the Post repeatedly violated its own rules and failed to address convincing evidence that this key element of the story was false.

- A February 24, 2024, story about a Palestinian anesthesiologist who fled his Khan Yunis hospital “with a heavy heart” because he said he feared facing “one of three fates in wartime Gaza: displacement, detention or death.” He told a riveting, gruesome story of surviving a series of checkpoints only because “he was carrying a baby that he found abandoned in the chaos of the evacuation.” None of this was corroborated by any other sources, however, except for general comments offered by a longtime official of Hamas’s Ministry of Health, raising red flags that a senior editor should have addressed.

- An April 8, 2024, story about civilians returning to the rubble of war-ravaged Khan Yunis, which opens with an unnamed Palestinian aid worker lamenting that his house had “vanished,” with “piles of rebar and cement” in its place. Why the Post had to resort to an anonymous source when tens of thousands of Gazans faced this predicament upon their return to Khan Yunis was never explained.

In three of these five stories, the lead reporter was Jerusalem-based Miriam Berger; in the other two, the lead reporter was Hazem Balousha, a longtime contributor to the Post, the Guardian, and Deutsche Welle who relocated from Gaza to Amman with his family early in the war. Overall, 48 Post reporters or contributors had bylines on Gaza stories citing anonymous sources, but these two were the most frequent, with Berger’s name on the byline of 39 percent of all such stories and Balousha’s on 22 percent of them. On four occasions, Berger and Balousha shared a byline on an anonymously sourced story, meaning that one or both were listed on more than half (51 percent, 21 out of 41) of all these stories.

***

The story is very different for the other major U.S. news media included in the Institute’s database. For those six other news organizations, use of anonymous sources in Gaza war reporting ranged between rare and nonexistent.

Unlike the Post, which frequently drew upon anonymous sources for colorful quotations or scene-setting observations, other news media generally restricted such use to providing factual information not available elsewhere. As for the New York Times specifically, it cited unnamed local people more than any media platform besides the Post, but all eight stories did so to relate factual information—e.g., a Red Crescent paramedic confirming the number of fatalities in an Israeli air raid, a family member confirming the identity of an Israeli hostage in a Hamas-produced video, Palestinians in Rafah confirming Egyptian military engineering works along the border with Gaza. In none of the Times’s articles is the unnamed source given a platform to offer an opinion or just provide additional color. Cumulatively, these eight stories include the bylines of seventeen different reporters, with none appearing more than twice. In short, the Times appears to have done a commendable job of following its in-house rules on use of anonymous sources in its Gaza war reportage—namely, “The use of unidentified sources is reserved for situations in which the newspaper could not otherwise print information it considers newsworthy and reliable.”

Examples elsewhere include the CNN story on March 28, 2024, that cited an unnamed eyewitness who feared reprisals for telling the network that 400–500 Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad members had arrived at al-Shifa Hospital in mid-March and the April 19, 2024, NBC News story citing the relative of an American held hostage in Gaza who discussed conversations with Israeli security forces about the status and whereabouts of hostages “on condition of anonymity to avoid putting their loved one’s fate at risk.” Both of these were clearly bona fide reasons to give a source anonymity. Indeed, there are exceedingly few examples of the use by media other than the Post of anonymous sources for solely descriptive comments.

***

What is the takeaway from this exercise? Quite apart from accusations of advocacy, bias, or partisanship, these findings point to serious professional journalistic failings that distinguish the Post from the other six U.S.-based media organizations included in the database. Indeed, abuse of anonymous sourcing at the Post appears to be a systemic problem, with responsibility that runs from correspondents in the field to the most senior editors in Washington. This may not be the reason the Post is currently going through convulsive change, but one can only hope that it comes out at the other end with this problem fixed.

* Kyle Robertson, a research assistant at The Washington Institute, created the “Gaza War Reportage Anonymous Sources Database,” from which this paper draws its analysis.