Assessing the Latest Houthi Maritime Threats

Part of a series: Maritime Spotlight

or see Part 1: Tracking Maritime Attacks in the Middle East Since 2019

Even increased aggressive activity in the Indian Ocean will be unlikely to seriously disrupt maritime traffic and global trade—but vessels calling on Israeli ports will need to take extra precautions.

The Houthi-led maritime campaign against commercial shipping entered a new phase in November 2023 with the launch of unrelenting drone and missile strikes against shipping in the Red Sea, Bab al-Mandab Strait, and Gulf of Aden in support of Palestinians in Gaza. Earlier this month (May 2024), the Yemeni group vowed to further intensify and expand its attacks in the event Israel’s threatened invasion of Rafah proceeds. Now that the invasion has begun, any shipping company with vessels that have ever called on Israeli ports will become a potential target for the Houthis, and not necessarily limited to the Red Sea or Gulf of Aden, according to the group. Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, the group’s leader, articulated its position in a May 9 televised speech: “As long as a company sends vessels to Israeli ports, we will take measures against [its ships] anywhere within our reach, regardless [of whether] a ship is transporting goods to the Israeli enemy at the time of the attack or not.” The Houthis have labeled this escalation the fourth phase of their campaign.

MSC and Other Shipping Targets

The Yemeni group appears to have already expanded its attacks into the northwestern Indian Ocean, and more attacks will likely take place there against certain ships operated or owned by companies that cooperate with Israel. In recent weeks, the Houthis have been targeting vessels owned and managed by the Geneva-based Mediterranean Shipping Company, the world’s largest liner operator in the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean—and such targeting will likely continue. In September 2023, MSC struck an operational collaboration agreement with the Israel-based Zim Integrated Shipping Services that includes vessel sharing and swap arrangements. The cooperation includes services connecting the Indian subcontinent with the East Mediterranean, the East Mediterranean with northern Europe, and East Asia with Oceania. Cooperation with Zim is believed to explain the Houthis’ singling out of MSC ships for attack. MSC also has ships chartered from companies linked to Israel-born shipowners such as Eyal Ofer.

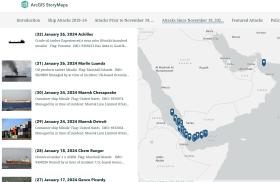

Since the Houthis launched their newest round of attacks on commercial shipping in November 2023, at least eight confirmed attacks and one threat have involved MSC-owned or-operated vessels in the southern Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Indian Ocean, according to data collected by the authors. Targets of the latest confirmed attacks include the MSC Gina and MSC Diego in the Gulf of Aden, as well as the MSC Orion, which was targeted by a suicide drone on April 26, about 200 nautical miles (370 km) southeast of Yemen’s Socotra Island while sailing in the Indian Ocean. No injuries or significant damage were reported in these latest attacks. The Yemeni group also claims to have launched at least seven attacks on MSC-affiliated ships in the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean—but these remain unconfirmed by independent sources.

MSC is not the only company that can expect stepped-up Houthi attacks in the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden—through which a few MSC ships have continued sailing to Djibouti. Other shipping companies (intentionally left unnamed in this post) that call on Israel’s ports could also face attacks on their vessels.

Potential Attacks in the Mediterranean

Although warnings have emerged of potential Houthi attacks toward the Mediterranean, mainly using drones or cruise missiles, such long-range attacks should have a range of over 2,100 km, and can be intercepted by Israeli and other regional air defense systems—in the same way attacks on Israel’s Red Sea port of Eilat can be intercepted. Only the Sammad-4 drone is claimed by Houthis to have a range of 2,000 km. The Yemeni group will thus likely focus on its area of operations in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Indian Ocean and delegate any antiaccess/area denial (A2AD) operations in the Mediterranean to other members of the “axis of resistance.”

Hezbollah, for example, has signaled the potential for attacks on Israeli ships, but should the Gaza war escalate further, the group could initially use “Hamas and the other members of the axis of resistance” as cover to launch or route attacks at Israel-bound shipping or Israeli offshore gas production facilities from or through Lebanese territory. Syria will likely stay away from such endeavor at the behest of Russia. Iraqi armed groups may attempt to launch more drone and cruise missile attacks, but this risk does not appear high at the moment given the fact that Iraqi groups have already claimed launching eighty-two “air-breathers” at Israel since November, with a significant increase beginning in March— yet they barely reached Israel or caused any damage. A further increase in such attacks will likely hinge on the trajectory of the Gaza war and additional Iranian involvement. On May 7, Gen. Hossein Salami, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), publicly announced his axis’s plan to “deny the enemy’s access to East Mediterranean” and to “expand the frontline in order to thin out the enemy.”

A broader historical lens shows the Mediterranean to be the site of shipping attacks in the Iran-Israel shadow war. For instance, in 2021 the Iranian container ship Shahr e Kord sustained damage in what was seen as a possible Israeli attack in response to Iran’s attacks against Israel-linked ships. Earlier, on two occasions (June 2019 and January 2020), underwater sabotage attributed to Israel severed Syrian submarine oil pipelines connecting a floating single point mooring to Syria’s Baniyas refinery, which regularly received Iranian crude oil.

Possible Impact on the Flow of Commodities

Since the Houthis began their maritime attacks in late 2023, the authors have not observed a noticeable disruption in the supply of various commodities, including oil and gas, through the region’s waterways. The major impact has been on transportation of cargoes between different regions, given that many ships are avoiding the Red Sea and taking the long haul around the southern tip of Africa, adding weeks of transit time, and raising shipping costs. Even if the Houthis target more vessels in the Indian Ocean, maritime traffic and global trade are unlikely to experience major disruptions. Still, some shipping companies that have vessels calling on Israeli ports will need to take more precautionary measures while navigating the Indian Ocean and the region’s waterways.

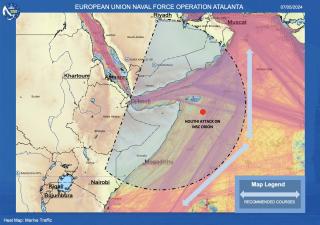

For the European Union’s Naval Force (EUNAVFOR), the attack on the MSC Orion in late April confirmed that attacks can occur in the Indian Ocean “up to 800 nautical miles (1,500 km) from the areas under Houthi control in Yemen" (see the above map). EUNAVFOR recommended that vessels establish “an alternative sea route no less than 150 nautical miles (278 km) east of the current traffic routes,” and also implement other measures to reduce positional exposure. The above radius of coverage relates to the one-way attack drone threat, while the Houthi antiship ballistic missile threat is not assessed to reach anywhere beyond the Gulf of Aden median line for now.