What Does the Red Sea Crisis Reveal About Sanctioned Ships?

Part of a series: Maritime Spotlight

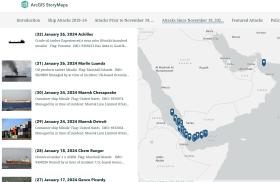

or see Part 1: Tracking Maritime Attacks in the Middle East Since 2019

Two sanctioned Russia-linked oil tankers, which were attacked by the Houthis in 2023 and 2024, recently changed their names and are flying the Djiboutian flag amid stricter Western sanctions.

In 2024, the Washington Institute’s Maritime Spotlight explored several trends in the Houthi maritime campaign, captured in this maritime incident tracker. These included attacks on tankers transporting Russian oil that were struck by the Houthis as a result of outdated shipping information. Maritime Spotlight’s latest research shows that the Houthi campaign has indirectly brought attention to ships carrying Russian cargoes, including via the Red Sea to Asia—particularly India and China, the key purchasers of Russian oil. As Britain and the United States recently imposed strict, sweeping sanctions against ships linked to the Russian oil trade—known as the shadow fleet—some vessels began changing names and flags, a common practice for sanctioned ships seeking to evade restrictions and obfuscate the process of tracking them. These include a couple of vessels attacked by the Houthis in 2023–24 based on outdated information that recently changed names and are now flying the Djiboutian flag. In recent years, sanctioned vessels have adopted the flag of this East African country, including tankers linked to the Iranian and Venezuelan oil trade.

Apar (Formerly Andromeda Star)

The European Union–sanctioned, Djibouti-flagged crude oil tanker Apar (IMO 9402471), formerly known as Andromeda Star (flagged to Panama), gained attention twice in 2024. The first time was in March, when it was involved in a collision in the Danish straits. According to some reports, the tanker was sailing with invalid insurance and was scheduled to load Russian crude oil at the port of Primorsk. The following month, the tanker was attacked by Houthis in the southern Red Sea while on a voyage to deliver crude oil to India. The Yemeni group used three antiship ballistic missiles against the tanker, which was broadcasting “no contact with Israel,” a message used by many ships sailing through the southern Red Sea to avoid Houthi attacks (see The Washington Institute’s maritime incident tracker). While the Houthis claimed Apar was “British,” Washington Institute research shows that this information was outdated.

Between December 2023 and December 2024, Apar was involved in moving Russian oil at least three times to India and China, as confirmed by TankerTrackers.com, a maritime intelligence company that specializes in following the global shadow fleet. Automatic Identification System (AIS) data from MarineTraffic shows that the tanker changed its name from Andromeda Star to Feng Shou and then Apar during a short period in December 2024, which was when it also transferred its flag from Panama to Djibouti—a change confirmed by Lloyd’s List Intelligence analyst Bridget Diakun. There are several known cases in which ship flag registers (including Djibouti and Panama) had to deflag sanctioned vessels. It remains to be seen if Apar and other sanctioned vessels will continue using the Djiboutian flag.

AIS shipping data from MarineTraffic and the market intelligence firm Kpler shows that Apar was mainly in Chinese waters toward the end of 2024. It was last seen in the Red Sea in July 2024.

Lahar (Formerly Sai Baba)

On December 23, 2023, a few weeks after the Houthis launched their maritime campaign as a way to support Hamas in the Gaza war, the Gabon-flagged crude oil tanker Sai Baba (IMO 9321691) was targeted by a Houthi one-way attack drone. The U.S. Navy destroyer USS Laboon (DDG 58), which was patrolling the area, responded to the distress call of the tanker, which was on its way to India with a Russian oil cargo.

In October 2024, the British government, as part of what was described as its “biggest wave of sanctions” against the Russia-linked shadow fleet, added Sai Baba to its list of sanctioned vessels. Later in December, the ship switched from the Gabonese to the Djiboutian flag, and as of January 14, 2025, the vessel’s name appeared to be Lahar, not Sai Baba. It was, like Apar, seen in Chinese waters toward the end of 2024. The last time it was identified in the southern Red Sea was August 2024, based on AIS data from MarineTraffic.

The Red Sea’s Importance for Russian Oil

Both Apar and Lahar, as well as other Russia-linked tankers, continued to use the Red Sea route after the Houthis attacked them in 2023 and 2024, largely based on inaccurate information. While many commercial ships in the Gulf of Aden and southern Red Sea were significantly affected by the Houthi attacks (see the Institute’s recent analysis here), Russia-linked ships do not appear to have been similarly affected. According to a Kpler research note published on December 6, 2024, “Russian crude oil has been the only cargo type that has not seen a reduction in [the] Suez Canal.” Tankers transporting Russian oil that were attacked by the Houthis were not deterred by the very high risks, and continued sailing in the region instead of taking the longer route around the Cape of Good Hope (see this Maritime Spotlight post). According to the Kpler research note, the share of Russian crude exports via the Suez Canal averaged around “55% in 2024, in line with last year’s [2023] levels.”

The author’s research indicates that one of the latest cases involves the oil tanker Blue Lagoon I (IMO 9248447), which the Houthis targeted more than once in September 2024 in the southern Red Sea. The vessel was carrying an oil cargo loaded at Russia’s Ust-Luga oil terminal, and its AIS signaled “RUS ORIG CGO ONBOARD” (Russian-origin cargo onboard), according to data from MarineTraffic. While some sources suggest that the ship may have been targeted because the owner had vessels visiting Israel, no solid evidence confirms this, and most likely the tanker was attacked based on inaccurate data. Moreover, as of January 9, 2025, the Blue Lagoon I was sailing again in the southern Red Sea on its way from India to the Suez Canal, with its AIS switched on. Shipping data indicates that the tanker’s navigation was smooth, and the Houthis did not attack the ship this time.

A Washington Institute analysis published last year noted that some China- or Russia-linked ships that were attacked due to inaccurate information later sailed in the Red Sea without incident, possibly indicating that they could now sail safely off Yemen. Meanwhile, as of December 21, 2024, the Houthis were still launching attacks over the Red Sea amid U.S. strikes against their military sites in Yemen. U.S. Central Command indicated on December 21 that U.S. forces shot down multiple Houthi one-way-attack uncrewed aerial vehicles and an antiship cruise missile over the region. Between December 1 and December 10, the Houthis launched two separate attacks against a convoy consisting of two U.S. destroyers, the USS Stockdale and USS O’Kane, escorting U.S.-flagged merchant supply ships heading to Djibouti (see the maritime incident tracker). While the attacks were foiled, they signaled that the Yemeni group was still defiant that month. Attacks against commercial ships, however, have diminished, as seen in this infographic, dropping from fifteen in June to only three in November. In December 2024, there were only two incidents involving U.S.-flagged merchant supply ships in the Gulf of Aden (see the maritime incident tracker). This is partly because other shipping companies left the region toward the end of 2024, opting to take the Cape route, in response to the intense fourth and fifth phases of the Houthi maritime campaign, which occurred between May and December 2024.