- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

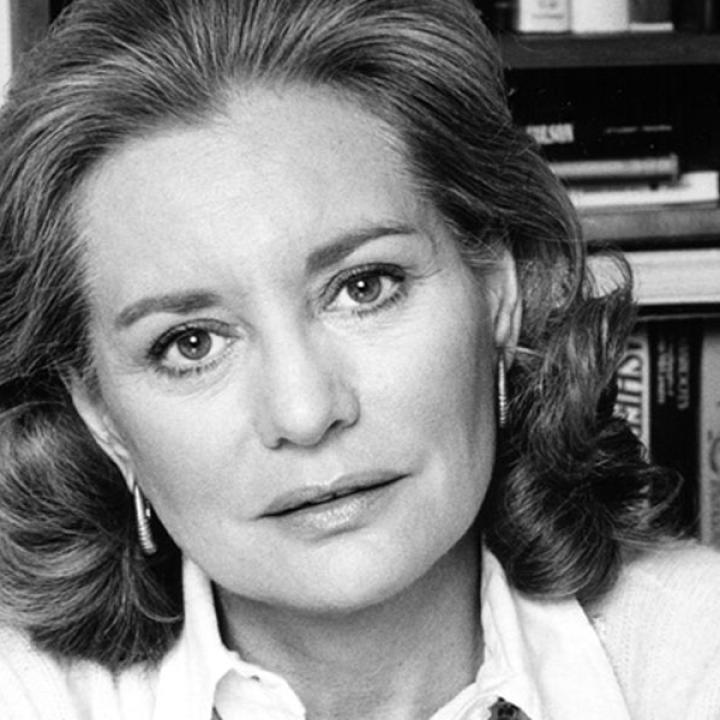

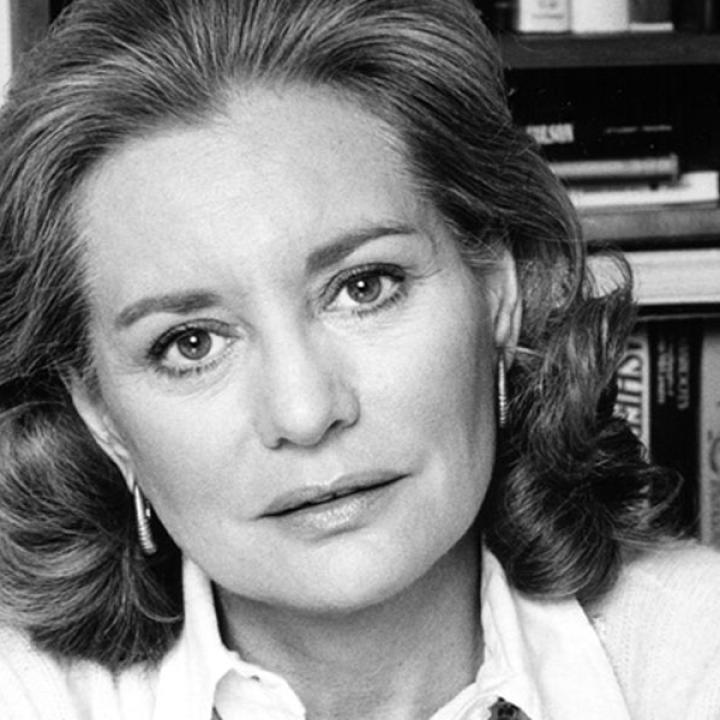

Barbara Walters, Impresario of Peace

Reflections on the late journalist's role in shepherding landmark conversations (and dinners) between Israeli and Arab officials.

Celebrity journalist Barbara Walters, who died last Friday at the age of 93, owed much of her fame to her interviews with Middle Eastern leaders. These included the Shah of Iran, Saddam Hussein, Mu’ammar Qaddhafi, King Hussein of Jordan, King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, King Abdullah of Jordan, Moshe Dayan, Golda Meir, and Yasir Arafat.

But none of these interviews made a splash like the one she conducted on November 20, 1977, in a room at the Israeli Knesset in Jerusalem. The interviewees: Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat.

She interviewed them together, in the tumult of Sadat’s surprise visit to Jerusalem and just after they’d delivered their addresses to the Israeli Knesset. The joint interview was a breakthrough, and Walters later gave a riveting account of how it came about. (Begin told her he had asked Sadat to do it “for the sake of our good friend Barbara,” and Sadat agreed.)

Walters had scored a scoop. In her memoirs, she called this “the most important interview of my career.” But the answers she got didn’t advance Israel and Egypt toward an agreement by one iota. Walters tried her best, probing for possible concessions from both leaders. “You are always like this, Barbara,” Sadat gently chided her. “Politics can not be conducted like this.” Her reply: “I have to keep trying.”

The bonhomie in the room failed to conceal the deep differences between Begin and Sadat, in those earliest days of a negotiation that would last years. Journalism isn’t diplomacy: divergent interests can’t be reconciled by media celebrities operating in the glare of lights. Sadat used Walters, and before her Walter Cronkite (who’d spliced together interviews with Sadat and Begin) to push a distracted Carter administration into action. Once U.S. diplomacy kicked in, the news blackout went up, and even Walters found herself prowling the perimeter of Camp David.

Fraternize? Already?

A footnote to the Knesset interview has been forgotten, but deserves a retelling. The tireless Walters was already on the hunt for her next scoop, and she opened the interview with a series of questions meant to set it up. The exchange went like this:

Walters: After tomorrow, your ambassadors, for example, your two ambassadors in Washington can meet and talk?

Sadat: Why not?

Walters: Well, because they never have before.

Sadat: It has never happened, yes. But, as I said today, we are ready.

Begin: There shall always be a beginning and I can only express my deep satisfaction at the words uttered by the president. I do hope that, starting from tomorrow, the ambassadors of Egypt and Israel all over the world will give common interviews with journalists and express their opinions and that will apply also to the United Nations.

(Watch this exchange here, at minute 19:45.)

This back-and-forth confused Egyptian ambassadors all over the world. Sadat’s visit had already plunged Egypt’s foreign ministry into turmoil: the foreign minister, Ismail Fahmy, had resigned two days before the trip. Sadat’s remarks in Jerusalem now deepened the uncertainty, complicated by his answer to another question posed by Walters: “Do you still consider that you are in a state of war?” Sadat: “Unfortunately, yes.”

A “diplomatic source” tried to clarify the situation for the New York Times: “Mr. Sadat’s televised sessions in Jerusalem left Egyptian ambassadors abroad unsure whether they, too, should begin fraternizing with Israeli counterparts. The instructions now emanating from Cairo are that the President’s trip was an exceptional diplomatic maneuver and should not be construed as a signal for warmer contacts.”

This did not take into account the dogged determination of Barbara Walters.

Walters counted among her Washington friends the suave Ashraf Ghorbal, Egyptian ambassador and an old pro. A Harvard PhD, he had been in the Egyptian diplomatic service for almost thirty years. He’d run the Egyptian interests section in Washington after 1967, did a stint as a security adviser and press spokesperson for Sadat, and returned to Washington as ambassador upon the resumption of U.S.-Egyptian relations in 1974. Ghorbal knew how to roll with the punches. Unlike Fahmy, with whom he’d had a sharp rivalry, he would stick with Sadat. (Rumors even labelled him a candidate for foreign minister.) But how far would he go? This is what Barbara Walters set out to test.

Who’s Coming to Dinner?

As soon as Sadat left Jerusalem, she went straight to Ghorbal and to Israel’s ambassador to Washington, Simcha Dinitz, another career pro. Would they agree to be interviewed together on ABC News’s Sunday afternoon weekly, Issues and Answers? A foreign ambassador couldn’t dream of more media exposure than that.

Dinitz agreed, but Ghorbal demurred. He was prepared to meet Dinitz, but not on television. Fine; would Ghorbal meet Dinitz before an audience? Ghorbal agreed, provided the meeting was off the record.

How could Walters leverage an off-the-record meeting into the talk of the town? Her solution: invite an A-list of officials and media celebrities to dinner. ABC, Walters’ network, booked a banquet room at the Madison Hotel, and she invited fifty people to dinner in honor of the two ambassadors. Yes, it would be off the record, but word would reach all the right people. Perhaps that would set the stage for another scoop. After all, the Israeli-Egyptian show had only just begun.

The list of RSVPs glittered. From the Carter administration: Zbigniew Brzezinski (National Security Advisor), Hamilton Jordan (President Carter’s chief political advisor), and Robert Strauss (U.S. Trade Representative). From the media: Roone Arledge (president of ABC News, and co-host of the dinner), Ben Bradlee (Washington Post editor), Art Buchwald (Washington Post columnist), Sam Donaldson (ABC White House correspondent), Katherine Graham (Washington Post owner), Peter Jennings (ABC chief foreign correspondent), Sally Quinn (Washington Post style reporter), and William Safire (New York Times columnist). From the Hill: Tip O’Neill (House Speaker), Jim Wright (House Majority Leader), and Abe Ribicoff (an influential Jewish senator). From the diplomatic corps: Ardeshir Zahedi (Iran’s flamboyant ambassador).

And the guest of guests: Henry Kissinger, who as secretary of state in the previous Nixon administration had negotiated not one but two military disengagement agreements between Israel and Egypt, in 1974 and 1975.

Dinner was served on the evening of December 4. When Kissinger’s turn came to speak, he quipped: “I have not addressed such a distinguished audience since dining alone in the [Versailles] Hall of Mirrors.” But the significance of the evening didn’t arise from the toast offered by Kissinger, or the compliments exchanged by Ghorbal and Dinitz (for which there is no record). Rather, it brought some of the Jerusalem pageant to Washington, and made Washington stand up. People Magazine called the dinner “a political and conversational watershed.” William Safire described the atmosphere for readers of the New York Times: “There, in that room, at that moment, not even the most cynical media satrap present could help but be touched by the drama of the beginning of communication between two strong spokesmen of nations that have spent a generation at war.”

Strictly speaking, it wasn’t a “get” for Walters. (That’s the term for landing a big interview.) It was much more of a “give.” The day of the event, the Washington Evening Star ran a gossip piece, describing the planned dinner as a sequel to the carnival of “media diplomacy” that had unfolded in Cairo and Jerusalem. Walters pushed back: there had been no press release, there would be no broadcasting, no ABC cameras, and no diplomacy. “If the dinner could have been held in New York,” she insisted, “I would have had it in my home.” Did the dinner add to her luster? Of course. Did it do anything for her Nielsen ratings? Not a bit.

More Than a Meal

The dinner had two other probable effects. First, it may have helped galvanize the Carter administration. Sadat’s move had caught Carter’s people flat-footed. “There’s a general confusion in the Middle East about specifically what we should do next,” Carter wrote in his diary the week after Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem. “The same confusion exists in the White House.” The confusion showed at the Madison Hotel fete. Brzezinski, Carter’s national security advisor, lasted through the drinks but left before the dinner. That raised some eyebrows: why didn’t he stay to propose a toast? Jordan, Carter’s political advisor, was reported to have behaved boorishly: he’d had one too many, and, staring at Mrs. Ghorbal’s bodice, declared: “I always wanted to see the Pyramids.” True or not, the episode sparked a gossip piece in every newspaper and a full-column news story in the New York Times.

The dinner came as one more reminder to the Carter administration that it had to start looking proficient and proactive, and do it fast. The CIA had just produced a profile of Sadat, saying he had a “Barbara Walters syndrome,” meaning a sense of self-importance inflated by the media. But who could blame him? She took him seriously; Carter’s people didn’t. The administration needed to get the peace process into its pipeline (and away from Kissinger). The dinner probably accelerated that.

Second, it launched a different kind of show, starring Ashraf Ghorbal and a succession of Israeli ambassadors. Off-the-record went out the window: Sadat wanted to persuade American Jews to back Israeli concessions, and Begin wanted fast normalization. How to do both? Get the affable Ghorbal in front of American Jewish audiences, in an all-smiles show of camaraderie with Israel’s ambassador.

So the Ghorbal-and-Dinitz show went on the road, to synagogues and banquet halls. The biggest encore took place a year after the Walters dinner, at an Anti-Defamation League (ADL) luncheon for 250 guests in the ballroom of the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. Kissinger delivered his one-liners, Ghorbal and Dinitz talked peace, and Barbara Walters (along with news anchors Walter Cronkite and John Chancellor) received ADL awards for giving “enormous impetus and thrust to the peace process between Israel and Egypt.” The applause must have been thunderous.

In March 1980, the show finally reached America’s big top. Carter had earned the right to play host, having personally hammered out the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel the previous year. To mark the first anniversary of his triumph, he summoned Ghorbal and Ephraim Evron (who’d replaced Dinitz on the Israeli side) to a celebratory reception held in the Grand Entrance Hall of the White House. Carter gave the keynote (humorless, of course), and the two ambassadors spoke their well-rehearsed lines.

Diplomacy and Spectacle

“We’ve been like Siamese twins,” Evron said of his many appearances with Ghorbal. “The public was intrigued by it.” Keeping the public intrigued was part of the process. Most of this fell on Ghorbal: by the time he’d finished in Washington, Dinitz and Evron had been followed by two more Israeli ambassadors. Ghorbal finally retired in 1984. The Washington Post remarked that “the joint appearances of Ghorbal and a succession of Israeli diplomats serving here during the past six years have been one of Washington’s enduring spectacles.” It endured because it was in the Egyptian interest. Ghorbal, like Sadat, understood that if you wanted to get something from Israel, complaining to the White House and the State Department would only get you so far. You had to charm American Jews, an art that Ghorbal perfected.

What he really thought of it all is hard to say. In his Arabic memoirs, written twenty years into his retirement, he didn’t mention any of it. By then, most of his Egyptian readers probably would have viewed all this shoulder-rubbing and glad-handing with Israelis and Jews as bordering on the treasonous. But he’d done his professional duty, and he’d done it well.

Barbara Walters went beyond hers. Books on the secret diplomacy behind the Egyptian-Israeli peace deal fill shelves. It’s hard to find even one serious article on the marketing of that peace. When that story finally gets written, Walters should get her own chapter. Naturally, pride of place will go to the famous dual interview in Jerusalem. But perhaps the dinner in Washington left the more lasting legacy. “This was, believe me, a major event,” Walters wrote in her memoirs. “Even today the Egyptian and Israeli ambassadors are rarely at the same dinner.” Indeed, and at this distance in time, it’s all the more extraordinary.

Martin Kramer is the Walter P. Stern Fellow at The Washington Institute. This article was originally published on his website.