- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3599

Between Maritime Law and Politics in the East Mediterranean

Given the region’s fraught history and piecemeal legal frameworks, the parties and their allies should focus more on the political, economic, and security concerns underlying their legal disputes.

On March 9, Israeli president Isaac Herzog met with Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Ankara, the first public visit conducted at that level in nearly fifteen years. Although the bilateral relationship saw notable highs and deep lows over that time, the two countries have maintained links in a wide range of areas, one of which came to the forefront during Herzog’s visit: energy security. This was hardly surprising given the urgent relevance of regional hydrocarbon supplies amid the Russia-Ukraine war, but Turkey and Israel had pressing reasons to discuss such issues well before the current crisis. In recent years, legal claims concerning natural gas exploitation in the East Mediterranean seemed to put the two governments at loggerheads, as Israel showcased its cooperation with Greece and Cyprus—countries with whom Turkey has often had antagonistic relations.

Now is therefore an appropriate time to take a closer look at the legal moves that Israel, Turkey, and other states have made on energy and maritime matters. To better understand the various bilateral agreements that have shaped or emerged from this activity, it is first important to examine the international treaty underlying most of them.

UNCLOS and the 1994 Agreement

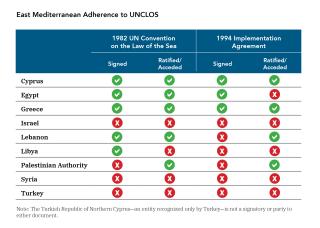

Contemporary international maritime law is widely understood to be based on the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the 1994 “Agreement Relating to the Implementation of Part XI” of the convention. To convince more signatories to ratify UNCLOS, the 1994 agreement focused on a limited, significantly diluted set of the convention’s provisions regarding seabed issues. Even so, adherence is still not universal; there are 168 parties to UNCLOS and 150 parties to the 1994 agreement. All of these parties are UN member states except the Cook Islands and Niue (both in free association with New Zealand), the Palestinian Authority, and the European Union.

In the East Mediterranean, certain countries have not signed UNCLOS or become parties to it; neither has the United States, though it did sign the 1994 agreement. According to some international legal scholars, UNCLOS enshrines customary law and is therefore relevant to states and entities who are not party to it, but this view is not universal.

Regarding the delimitation of maritime zones, UNCLOS distinguishes between the following: the territorial sea (up to 12 nautical miles from a coastal state’s “baselines,” defined as low-water lines along the coast as marked on official charts); the exclusive economic zone, or EEZ (up to 200 nautical miles from the baselines); and the continental shelf (defined in geological terms and extending beyond the 200 nautical miles). Under UNCLOS, a coastal state possesses near-total sovereignty over its territorial sea, but sovereign rights over an EEZ or continental shelf concern the exploration and exploitation of natural resources and are therefore of an economic nature. In case of claims by opposite or adjacent coastal states, UNCLOS stipulates that these zones should be delimited “by agreement...in order to achieve an equitable solution” (Articles 74(1) and 83(1)).

Regional Agreements

Given the mostly enclosed nature of the East Mediterranean, several coastal states have felt compelled to enter various agreements over the past two decades in order to demarcate their EEZs and continental shelves. In 2003, Cyprus and Egypt were the region’s first countries to conclude an agreement delimiting their EEZs. Cyprus went on to sign an EEZ agreement with Lebanon in 2007—a move heavily protested by officials in Turkey, who argued that the “Greek Cypriot Administration of Southern Cyprus” (the island’s internationally recognized government) did not represent the whole population, and that the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” also held claims to surrounding maritime areas.

Meanwhile, Lebanon appeared to circumvent its deal with Cyprus in subsequent years. After failing to ratify the agreement, Beirut unilaterally sent the UN secretary-general lists of coordinates for its EEZ in 2010, amended in 2011. These lists not only diverged somewhat from the Cyprus agreement, they also encroached on what Israel considered to be its EEZ. Cyprus and Israel had signed their own EEZ delimitation agreement in December 2010, after the vast extent of gas reserves in the waters between them had become clear. Israel’s Tamar and Leviathan gas fields were the first to begin producing, and Cyprus discovered the Aphrodite field in 2011 (still awaiting production). In 2015, Egypt’s Zohr field was discovered (currently in production).

In this context, broader geopolitical ties between Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, and Israel intensified without Turkish participation. During the Libyan civil war and other regional developments, these four countries and Turkey increasingly found themselves supporting (in actions or words) opposite sides. Thus it came as no surprise when Ankara’s 2019 memorandum of understanding with Libya’s “Government of National Accord” proposed maritime zones that would be adjacent over a distance of eighteen nautical miles, thereby cutting off any Cypriot, Egyptian, Israeli, Lebanese, Palestinian, and Syrian zones from Greece and the rest of Europe. A year later, Greece and Egypt responded with a bilateral agreement on partial EEZ delimitation.

Other developments in 2020 included Greece signing an agreement on construction of the EastMed Pipeline with Cyprus and Israel (initially with EU and U.S. support that was later withdrawn). The three countries also institutionalized their energy ties by partnering with Egypt, Italy, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority to found the East Mediterranean Gas Forum. France and the United States joined the forum in 2021 as a member and observer, respectively.

International Law or Politics?

The legal basis for economic delimitations in the East Mediterranean remains rather piecemeal. Israel, Syria, and Turkey are not parties to UNCLOS, the latter because the treaty’s treatment of islands puts it at a disadvantage with respect to Greece. Moreover, the status of existing delimitation agreements is sometimes unclear or inconclusive, as shown by Lebanon’s unratified deal with Cyprus and the partial EEZ delimitation reached by Egypt and Greece. As for the Turkey-Libya “memorandum,” political leaders worldwide regard it as controversial, the parties took nearly ten months just to register it with the UN Secretariat, and a Libyan national court ruled that it was not concluded by a competent authority, reflecting the country’s ongoing internal power struggle.

In such circumstances, political rationales often trump legal considerations. For instance, Turkey’s eagerness for energy collaboration with Israel cannot be discussed in isolation from questions about the Ukraine war and international reliance on Russian gas. Likewise, the question of whether renewed Israel-Turkey ties will lead to more legal clarity and economic cooperation in the East Mediterranean is bound to depend on political developments above anything else. Notably, Israel was represented by its president at the recent Ankara meeting, while the government ministers who define policy remained at home.

More broadly, observers must keep in mind that East Mediterranean actors have fraught histories and complex webs of alliances and antagonisms, such that a wide array of political, economic, and strategic considerations tend to steer their behavior. This includes instrumentalizing international law to legitimize strategic moves. It therefore seems wise not to focus overmuch on the technicalities of their legal tussles, but to instead confront underlying political, economic, and security concerns head-on.

Dr. Alexander Loengarov is a visiting fellow with the international and European law program at Vrije Universiteit Brussel and a former official at the European Economic and Social Committee. This PolicyWatch solely expresses his views and does not reflect in any way the opinion of the above committee or the European Union, which cannot be held responsible for any use made of it.