- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3456

Expanding Humanitarian Assistance to Syrians: Two Deadlines Approaching

Syria may not be a priority for the Biden administration, but the Brussels pledging conference and the July vote on the UN cross-border mechanism mean that major donors can no longer keep the disastrous humanitarian situation on the back burner or expect NGOs to resolve it on their own.

Despite the relative reduction of violence in Syria, the humanitarian situation has deteriorated rapidly and dangerously over the past year. On nearly every metric—poverty rates, food shortages, access to clean water—Syrians are now faring worse than they did at the start of 2020. The international community will soon face two tests of its ability to address this urgent challenge: first next week, then again in July.

Four Humanitarian Realities in One Conflict

As of December, the UN estimated that over 80% of Syrian residents are living below the poverty line. According to the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 11.1 million residents are in need of humanitarian aid as of this year, while the World Food Programme estimates that 12.4 million people—or 70% of the population—are food insecure, a 50% increase from last year.

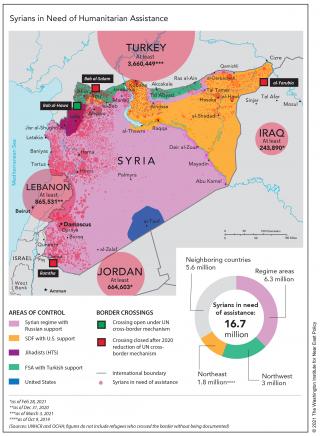

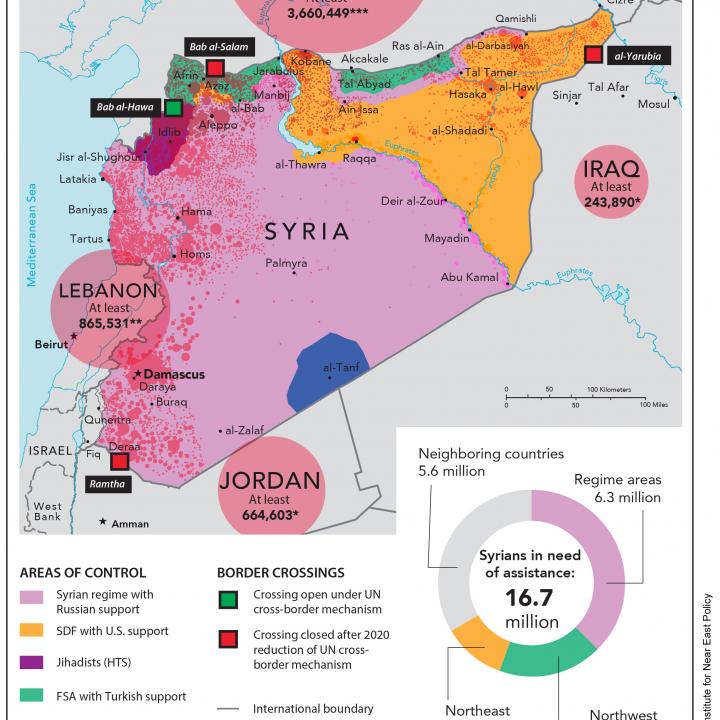

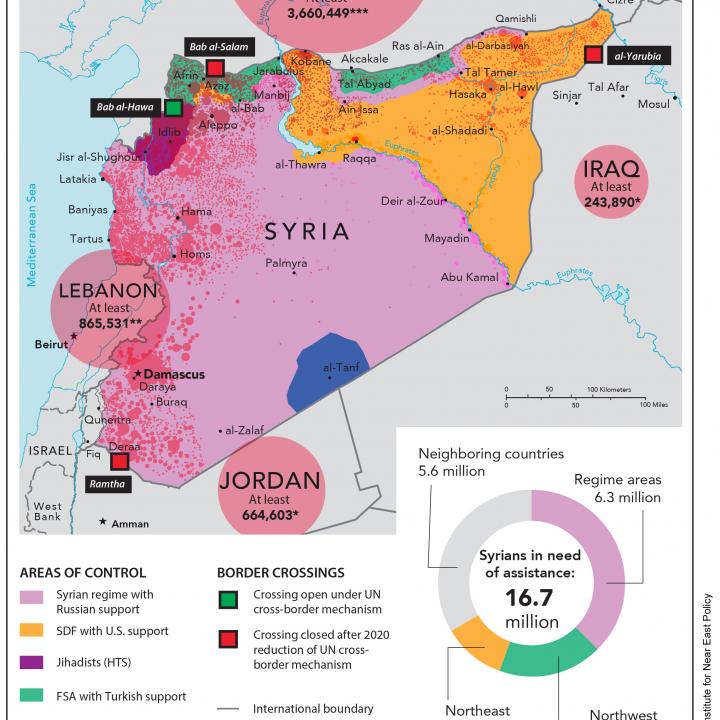

But even these alarming figures do not capture the full scale of the problem. In addition to the dire domestic situation, at least a quarter of Syrians—5.6 million people—are currently refugees in neighboring countries, and barriers to accurate counting mean that this figure is almost certainly an underestimate. Refugees now account for roughly a third of all Syrians in need, according to OCHA’s February regional funding update.

In total, then, at least 16.7 million Syrians are in need of humanitarian assistance across the region. Yet these needs and the systems intended to fill them are highly complex and fragmented. The Syrian conflict has produced at least four different humanitarian realities:

Syrian regime territory. The reasons behind the rapidly deteriorating economic situation in areas controlled by Bashar al-Assad’s regime are numerous and convoluted: they include large-scale destruction of reconquered opposition areas, the financial crisis in neighboring Lebanon, the regime’s distortion of aid, out-of-control domestic inflation, and international sanctions, among others. The black-market exchange rate for the Syrian lira has increased threefold since early 2020 alone, making basic goods prohibitively expensive for even formerly middle-class residents. The cost of a food basket to sustain a family of five for a month has risen fivefold since October 2019, and stories of rapidly growing lines for subsidized bread and other staples make clear that the crisis in regime territory has deepened in recent weeks.

Rebel-held territory in northwest Syria. Around 4 million people were estimated to live in this zone as of last year, including 2.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) from elsewhere in Syria. Of that number, the UN estimates that at least 3 million require some form of humanitarian aid. Due to severe overcrowding, the Idlib area controlled by the jihadist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) is in especially critical need of assistance with managing hygiene and access to clean water. Of the 2.7 million IDPs, OCHA estimates that 1.5 million are crowded into “last resort” sites, which are significantly over-capacity. UN-coordinated efforts delivered clean water to 2.1 million northwestern residents in January, but more than 44% of the local population relies on unsustainably expensive water provided by private trucks, according to survey data reported that month by the REACH initiative.

Northeast Syria. As of October 9, 2019—the most recent date for which comprehensive numbers are available—the northeastern zone largely controlled by the U.S.-supported Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) was home to over 3 million people, with 1.8 million requiring humanitarian assistance. Yet access to aid remains low, and these figures have likely changed a great deal in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and other developments. For example, in REACH’s January 2021 survey of needs, half of IDP communities in the northeast and two-thirds of non-IDP communities reported having no access at all to humanitarian goods and services, while 98% of respondents stated that residents in their communities had insufficient access to food.

Refugees in neighboring countries. Despite the relative ease of providing aid to Syrians in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan (the three largest host countries), their needs are far from being met. Overcrowding, funding shortfalls, and barriers to entering the formal labor market have created a desperate situation for much of the refugee population.

Compromised and Canceled Humanitarian Systems

The main challenge for humanitarian actors is getting access to those in need, since blockades, border closures, and other acts have repeatedly violated the international principle of unhindered access. The Assad regime is primarily responsible for these violations, consistently appropriating or restricting aid as a tool of war and even going so far as to strike humanitarian facilities, as happened in northwest Syria on March 21. Such actions are well-documented, but a struggle over interpretation of humanitarian law has allowed Russia and China to shield the regime from consequences through UN Security Council vetoes.

Specifically, Assad argues that he has an absolute right to control humanitarian aid distribution within Syria, even for territory outside his control, and Moscow has backed this assertion at the Security Council. The World Health Organization and other ostensibly neutral organizations have bent to Assad’s will, funneling more aid to regime loyalists than other constituencies in order to remain in the regime’s good graces. As a result, Damascus exerts outsize control over aid distribution, despite the fact that more than 60% of Syrians in need live outside regime territory. Indeed, Assad and Moscow’s sovereignty argument is a clear violation of international humanitarian law, which has long been understood to prohibit the suspension of aid to any groups of people for “arbitrary or capricious” reasons.

To better deliver aid directly to those in need, the international community set up a second system of assistance: the cross-border mechanism. In 2014, the Security Council approved a plan to send aid from Iraq, Turkey, and Jordan directly into opposition-held territory in Syria. Yet this lifeline has been threatened from its inception. The Assad regime maintained that the mechanism violated its sovereignty, while Moscow only accepted it temporarily, at a moment when the regime was particularly vulnerable prior to the 2015 Russian military intervention. Years of challenges from Moscow eventually culminated in a threatened veto at the UN, spurring the Security Council to cut the number of border crossings from four to two in January 2020, and then to just one in July.

The cancelation of the Iraqi portion of the mechanism left northeast Syria largely reliant on the Assad regime to receive UN assistance. A limited network of NGOs continued providing help from Iraq in order to deliver lifesaving aid, but they must operate mostly under the radar and cannot be scaled up to a sufficient level. Residents in the northwest may soon find themselves in the same situation if Russia exerts its veto power again this July, when the last entry point in the UN cross-border mechanism (Bab al-Hawa) is up for renewal.

Who Funds What?

In this fragmented landscape, funding is a major challenge. According to OCHA’s February regional funding update, only 7% of Syrian refugees in Turkey had their needs adequately met by UN assistance in 2020 (though some of that gap was filled by the roughly 6.5 billion euros that the EU has paid to Ankara since 2016 in exchange for greater assistance in preventing unregulated refugee crossings into Europe). Syrians in Lebanon and Jordan fared little better (17.5% and 15.4% of OCHA’s funding goals were met there, respectively), while those in need inside Syria received just 55% of the UN’s target funding.

Given Moscow’s self-assumed role as arbiter of aid distribution in the conflict, one might expect Russian humanitarian aid commitments in Syria to be substantial, but the opposite is true. With a total UN-documented contribution of $23.3 million in 2020, Russia accounted for just 0.5% of UN-coordinated aid. In contrast, the United States donated over $1.5 billion and EU members collectively donated the same.

These figures should be kept in mind as the EU prepares to host the Brussels V Conference on March 29-30 to raise funds and discuss solutions for the humanitarian catastrophe, and as the Biden administration reviews its Syria policy. Donors at the previous Brussels conference last June pledged over $7.7 billion, but the UN estimated that nearly $10 billion was required to fully meet Syrian humanitarian needs in 2020. Those needs are projected to grow in 2021, so the upcoming conference is a crucial opportunity to raise more funds and set realistic goals for how to distribute them to the people most in need.

European and North American countries have provided around 90% of humanitarian assistance to Syrians since 2011, so they have leverage to press UN agencies operating in regime territory to limit Assad’s appropriation of aid. These donors should also prepare joint alternatives to the UN framework in case the cross-border resolution is not renewed in July. They should form a united front and provide a crystal-clear message to Moscow: aid will be delivered directly to needy residents in the northwestern province of Idlib with or without a UN resolution that keeps the nearby crossing open. Moscow may complain about potential aid diversion to jihadist groups, but the reality is that this is the most-monitored aid delivery system in the world, and closing the Bab al-Hawa crossing would make monitoring more difficult. Alternatively, if the UN framework is preserved and, hopefully, improved, member states should be encouraged to provide additional funding for humanitarian operations.

Calvin Wilder is a research assistant in The Washington Institute’s Geduld Program on Arab Politics.