- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3847

Five Years After the Caliphate, Too Much Remains the Same in Northeast Syria

Islamic State fighters and affiliates detained there remain a regional threat that the international community must resolve in order to prevent a future resurgence.

This week marks five years since the Islamic State (IS) made its dramatic last stand in Baghuz, Syria. The group’s March 2019 territorial collapse greatly diminished its insurgency and left thousands of its fighters and affiliates detained in camps and prisons across northeast Syria. While some things have changed regarding the group’s status there, much remains the same. Many of the questions raised in March 2019 about IS and its detained populations are still being debated today, and new complications have arisen as well.

Despite its best efforts, IS has not been able to regain meaningful control over territory in northeast Syria, and its insurgency has been limited by successful coalition and partner operations. Yet the indefinite detention of people affiliated with the group—from Iraq, Syria, and approximately sixty other countries—remains an unresolved issue.

Further muddying the situation, many actors now operate in northeast Syria. The Global Coalition’s Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—the military wing of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES)—serve as the main fighting forces against IS in this area. Turkey, the Assad regime, Russia, and Iran have become involved as well, viewing the group as a threat to their interests. Although these secondary actors play a minor role in the fight, their local military operations, power plays, and sordid alliances have periodically undermined the coalition’s mission.

Amid all these dynamics, the security and political environment in the northeast has steadily deteriorated. Threats from outside actors, coupled with the SDF’s internal weaknesses, have distracted authorities from the ongoing counter-IS mission. Today, the SDF is unable to independently manage operations against IS or secure the detention facilities holding thousands of IS affiliates. Furthermore, the U.S. military presence in northeast Syria is under threat (logistically and perhaps legally), while next door in Iraq, authorities are seeking to end the coalition’s mission. If the international community wants to prevent an IS resurgence, it must prepare for a post-U.S. Syria and address the detainee dilemma head on, before the situation slips into further disarray.

Insurgency Weakens, Threat Persists

The coalition is currently in the fourth phase of its military mission, aiming “to advise, assist, and enable partner forces until they can independently maintain the enduring defeat of [IS] in Iraq and designated areas of Syria.” Its main kinetic partner in northeast Syria remains the SDF, which carries out counter-IS operations and controls the facilities holding IS affiliates. Yet the SDF lacks an air force and must therefore rely on the coalition for many of its operations.

In military terms, the counter-IS campaign has succeeded in decreasing the number of militants and terrorist operations in the area since 2019. According to the UN, the number of IS militants “at large”—meaning operatives actively fighting or supporting the group in Iraq and Syria—decreased from around 14,000-18,000 in February 2019 to 3,000-5,000 in January 2024. Counterterrorism operations have also eliminated four IS leaders and multiple senior operatives over this period, while the group’s attack claims in Syria have decreased annually, from 1,055 in 2019 to 608 in 2020, 368 in 2021, 297 in 2022, and 121 in 2023.

Yet IS seemingly remains intact despite these losses and has adapted to the methods used against it. The U.S. government recently warned that an IS resurgence cannot be ruled out in Syria. As of March 14, the group has already claimed 84 attacks in Syria this year, an uptick that departs from its previous underreporting of attacks there. IS fighters also reportedly remain committed to rebuilding their territorial “caliphate.” Moreover, the indefinite detention of tens of thousands of IS affiliates continues to exacerbate an already precarious situation.

Camp Numbers Decrease, But Overall Detainee Populations Hold Steady

The end of the “caliphate” left thousands of men, women, and children affiliated with IS detained in northeast Syria. These individuals were transferred to various pop-up prisons and detention camps in the AANES, many of which were originally designed as temporary shelters for internally displaced persons. The AANES gained de facto autonomy in 2012 during the Syrian civil war and continues to operate today with the coalition’s support, but its undefined formal status has further complicated the detainment issue and the wider security and humanitarian situation.

Today, the AANES and various NGOs operate several camps for Iraqis, Syrians, and “third-country nationals” (TCNs). Two of these camps—al-Hol and Roj—hold the vast majority of women and children TCNs who traveled to or were born in IS-held (and later AANES-held) territory. Both are closed sites, meaning individuals cannot leave without permission from camp administrators.

Between December 2018 and May 2019, al-Hol’s population increased from just under 10,000 to approximately 73,782 following the caliphate’s territorial collapse. Despite its current stigma as a camp housing IS-affiliated families, the influx of individuals into al-Hol also included people fleeing from the group. This rapid population increase created dire humanitarian circumstances and security concerns for camp residents, the majority of whom are women and children. Al-Hol has seen attacks against security personnel and residents, escape attempts, and external attackers attempting to breach the camp, though these have occurred at a much lower rate since late 2022.

After five years of repatriations and returns, al-Hol’s population currently stands at 43,446. Despite this significant decrease, however, IS ideology persists in the camp, and younger residents remain particularly vulnerable to indoctrination.

The smaller Roj camp currently holds approximately 2,600 individuals, including 2,100 TCNs. Established in 2014 for Iraqi refugees, it expanded in 2020 to accommodate more people, including TCN transfers from al-Hol. As of November 2023, approximately 91 TCN families had been relocated from al-Hol to Roj. In July 2023, Fionnuala Ni Aolain—at the time a special rapporteur for the UN Human Rights Council—stated that the situation in Roj was “somewhat better” than in al-Hol, but that conditions there were still harsh, with residents experiencing limited access to water, healthcare, and education.

Elsewhere, IS-affiliated men and teenage boys have been held in more than twenty mostly makeshift prisons since 2019. International backlash eventually led to the creation of more rehabilitation centers specifically for boys, but some of them are still being held in prisons alongside adult men. The overall prisoner population only recently dropped to approximately 9,000 in September 2023 after holding nearly constant at 10,000 since June 2019.

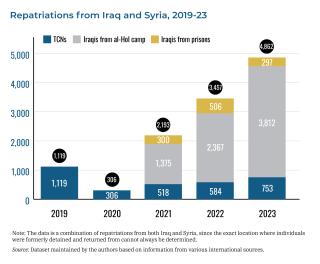

After the initial spike in returns in 2019, the international community has slowly increased its efforts to repatriate TCNs and Iraqis and return internally displaced Syrians from al-Hol, Roj, and other facilities (in some cases, Syrians and TCNs have been returned or repatriated from Iraq due to the cross-border movement of populations during the IS caliphate). Women and minors comprise the vast majority of repatriations today, as countries remain extremely reluctant to repatriate men and teenage boys held in prisons, often due to domestic political reasons. Despite numerous prison riots, breakout attempts, and the January 2022 Hasaka prison attack that left hundreds dead, the international community has not taken sufficient action to address this sector of the detainee population. Only the United States, Iraq, and certain Western Balkan and Central Asian countries have regularly repatriated individuals from prisons.

Since 2019, an estimated 9,300 Iraqis have been repatriated from Syrian camps and prisons, and an estimated 3,450 TCNs have been returned or repatriated from Syria and Iraq. In 2021, Baghdad began formal repatriation from al-Hol and struck an unofficial deal with the SDF, committing to receive 50 male prisoners for every 150 families it repatriated from al-Hol. Returning Syrians have been harder to track due to their country’s civil war and the nonstate status of the AANES, but some statistics stand out. In al-Hol, for example, Syrian residents have dropped from approximately 31,000 in 2019 to 16,500 at the end of 2023.

Next Steps

Although the status quo in northeast Syria remained mostly static over the past five years, some key factors appear to be shifting in troublesome directions of late. In Iraq—the main support base for U.S. and coalition operations in Syria—the government has signaled that it seeks to end the coalition’s mission. Since 2014, U.S. forces have operated in Iraq (and, by extension, Syria) at Baghdad’s invitation as part of the Global Coalition framework. By changing that military relationship, the legal basis and logistics bases that enable American operations in Syria could be removed, potentially forcing the United States and its partners to withdraw. Without a viable alternative in place, this would significantly decrease the effectiveness of international efforts to fight IS. In 2023, U.S. Central Command chief Gen. Michael Kurilla stated that if American forces leave Syria and the SDF proves unable to fight IS independently, IS affiliates could become radicalized in al-Hol and launch more prison breaks, potentially resulting in the group’s full resurgence in just one to two years.

Meanwhile, other actors continue to distract from the counter-IS mission. Turkish incursions and air campaigns targeting the SDF and its affiliates in northeast Syria have forced it to shift personnel and resources away from the IS fight and pause training. Iran-backed militants who have targeted U.S. personnel and interests in Iraq and Syria have also increased their attacks on the SDF. Tensions between the SDF and Arab tribes in Deir al-Zour are coming to a head as well, particularly since August 2023, when the SDF arrested a senior tribal leader and SDF commander over an alleged plot to expel the Kurdish-led force from northeast Syria.

The SDF’s internal weaknesses have likewise hampered the counterterrorism mission. The force is still limited to conventional operations against IS and reliant on the coalition for intelligence, air support, and other key tasks. And despite increased U.S. funding, training at SDF-administered detention centers was behind schedule as of December, and guards at prison facilities and al-Hol camp were cited for stealing humanitarian assistance, lacking the discipline to conduct proper patrols, being susceptible to IS bribes, and other problems. In short, the force is still not ready to fight IS, secure detention facilities, or prevent an IS resurgence on its own.

Increased normalization with the Assad regime could further destabilize the situation. Russia and Iran have long pushed this agenda, and the SDF has toyed with rapprochement as well, viewing Damascus as a potential alternative to the United States for shielding the AANES from Turkey. Yet the Assad regime and its allies have struggled to contain the IS threat themselves and should not be viewed as a viable replacement for the coalition. Moreover, if Damascus is permitted to fill the vacuum of a U.S. withdrawal, it could use the thousands of TCNs in the northeast as bargaining or blackmailing tools internationally.

Taken together, these factors show why the current approach toward detained IS affiliates is unsustainable. Although strides have been made to address this problem in the five years since the “caliphate” fell, the international community must act more assertively before the situation devolves further. Otherwise, the United States and its partners will be hard-pressed to meet their stated goal of defeating IS kinetically and ideologically.

Devorah Margolin is the Blumenstein-Rosenbloom Fellow at The Washington Institute. Camille Jablonski is a research assistant in the Institute’s Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence.