- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3809

The Gaza War’s Impact on Energy Security in the East Mediterranean

The energy sector is one indicator of the heavy costs the region will pay in the event of a wider conflict, with some effects already measurable in certain countries.

Prior to the Gaza war, natural gas discoveries in the East Mediterranean offered attractive prospects. As Israel boosted its gas production from 16.11 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2020 to 21.92 bcm last year, it expanded energy cooperation with Egypt. Washington, meanwhile, brokered a historic maritime boundary deal between Israel and Lebanon allowing the two to commence gas exploration and drilling in once-disputed waters. On the surface, the region appeared to be entering a phase of energy cooperation and security. Then came Israel’s war with Hamas.

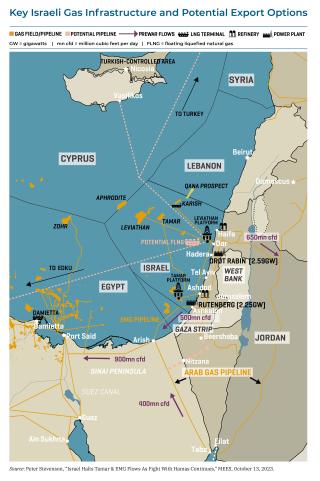

On October 9, two days after the surprise Hamas assault, Israel suspended output from Tamar, its second-largest gas field, due to safety concerns. This cast uncertainty over gas exports to Egypt, which has been grappling with rising domestic consumption. Subsequently, Israel’s oil terminal in Ashkelon was closed to vessels amid rocket attacks. And if the conflict broadens to include Hezbollah, it will exacerbate Lebanon’s already acute energy crisis.

Israel’s Prewar Gas Gains

In recent years, Israel has brought new offshore gas fields onstream, allowing it to increase production for the domestic market, reduce the use of more polluting fuels like coal for power generation, and expand its gas exports. During the first half of 2023, Israel took in over $263 million in natural gas royalties according to government figures, a 23 percent increase over the same period last year.

Before the 23 trillion cubic foot (tcf) Leviathan field came online in 2020, Tamar (13 tcf) had been driving Israel’s output since 2013, when it started production. (Both fields are operated by Chevron.) Last year, Israel’s gas production stood at 21.92 bcm, led by Leviathan (11.4 bcm) and Tamar (10.2 bcm). A total of 12.71 bcm was consumed domestically, mainly in the power sector, while 9.21 bcm was exported.

The development of Leviathan and Tamar, along with the smaller Karish field, which started production in October 2022, is forecast to add more than 15 bcm/year of supply by 2026. Such an increase could bring significant revenue to Israel. While the country’s potential gas exports to the European Union are less than 15 percent of the 155 bcm that Russia sold to the EU in 2021, before the Ukraine war, Israeli gas could be useful to European governments as they seek to diversify supplies and reduce their reliance on Moscow. To that end, the EU signed a memorandum of understanding with Egypt and Israel in June 2022 for shipping gas produced in either country to the continent via Egypt’s two underused liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities: the Shell-operated Edku facility and Eni-operated Damietta plant. Increasing output from Egypt, however, would require increasing production and developing infrastructure.

Gas Flows to Egypt: What’s at Stake?

Israeli government figures show that in 2022, 63 percent of its gas exports went to Egypt and 37 percent to Jordan. The exports to Egypt, which are transferred from Ashkelon to al-Arish, have been increasing since 2020. Last year, Israeli gas flows to Egypt via the East Mediterranean Gas (EMG) pipeline increased to 5.81 bcm, from 4.23 bcm in 2021 and 2.16 bcm in 2020.

While Egypt produces its own gas and aspires to become a regional hub for that sector, it has experienced a production decline in recent years, affecting its ability to meet domestic demand and export LNG. According to the Joint Organisations Data Initiative, Egypt’s estimated oil production during the first seven months of 2023 was 5.076 bcm, a roughly 12 percent decline compared to the same period in 2021. Meanwhile, Egypt’s LNG exports have declined in 2023 due to rising domestic consumption; at their current pace, they would total around 3.4 million metric tons by year’s end, compared to 7.1 million in 2022.

Amid rising domestic gas demand in summer 2022, Egypt was heavily reliant on Israeli imports, particularly to fuel the gas-fired plants that account for about three-quarters of its power supply. This affected its ability to maintain LNG exports. To fill the gap, Egypt arranged for increased gas exports from Tamar that August. This deal, which would have improved Israel’s revenues and bolstered diplomatic ties with Cairo, is now shrouded in uncertainty with production from Tamar suspended. On October 29, Egypt announced that gas flows from Israel had come to a halt, raising questions about its ability to resume LNG exports after a difficult summer.

War Disrupts Israel’s Oil Imports...

In the meantime, Israel’s crude oil imports were disrupted after it closed the Ashkelon terminal. Data from Kpler indicates that in September, 179,000 barrels per day (b/d) of Israel’s 205,000 b/d in crude imports came through Ashkelon and the rest via Haifa port. Since Ashkelon’s closure, at least one crude shipment has been imported via the Red Sea port of Eilat. Because most of Israel’s imports originate from the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, a protracted war could force more tankers to sail a longer route—through the Suez Canal to Eilat instead of Ashkelon, adding about four days to the trip and raising freight costs. According to Kpler, however, Israel had about 10.72 million barrels of crude in its inventories as of October 27, from which it can draw if needed.

This is the second time Israel’s oil imports have experienced interruptions this year. In March, flows of Iraqi Kurdish crude from Turkey’s Ceyhan terminal were halted due to an ongoing dispute between Baghdad, Erbil, and Ankara. As a result, Israel had to increase crude imports from other sources, mainly Azerbaijan (whose shipments to Israel are loaded at Ceyhan) and Kazakhstan (whose crude flows are carried by the Caspian Pipeline Consortium system and loaded at the Yuzhnaya Ozereevka Black Sea terminal near Novorossiysk, Russia). Yet replacing crude types is not always easy given that quality varies from one supplier to another, and the switch can lead to higher freight costs.

...And Amplifies Lebanon’s Energy Insecurity

Since 2020, Lebanon’s financial crisis has had a severe impact on its fragile energy sector. The government has been struggling to purchase oil product shipments to fuel four coastal power plants. Only the two running on gas oil—Zahrani in the south and Deir Ammar in the north—have been operating recently, albeit with frequent interruptions.

Amid severe power shortages, Lebanon’s private oil importers have increased imports of diesel, which is mainly used to operate private power generators. If Israel-Hezbollah tensions get worse, Lebanon’s caretaker government does not have the ability to address new emergencies. During the 2006 war, Israel bombed oil storage tanks at the Jiyeh power plant in southern Lebanon, causing a major spill of heavy fuel oil into the Mediterranean and leading to an environmental disaster. A wider conflict would also affect shipping traffic into Lebanon, increasing pressure on its struggling economy.

In 2022, the U.S.-brokered maritime boundary deal between Israel and Lebanon enabled offshore exploration activities in Lebanon’s southern region. Yet despite the country’s high hopes, drilling by TotalEnergies at the Qana 31/1 exploration well did not lead to the discovery of hydrocarbons. Lebanon’s politicians should now switch their attention away from gas pipe dreams to implementing long-delayed reforms.

Conclusion

Over the past few years, Washington has encouraged East Mediterranean states to diversify their energy sources, all the while tackling climate change. This energy diplomacy succeeded in some places, but the Gaza war has exposed the area’s high geopolitical risks. If the war expands, the hydrocarbon sector will not be spared the economic ramifications, and the energy plans of regional governments will be postponed for years to come.

Noam Raydan is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute.