- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3968

Houthi Shipping Attacks: Patterns and Expectations for 2025

Two experts offer a detailed infographic and accompanying analysis to chart attack trends over the past year and forecast what’s in store for the Red Sea and surrounding waterways.

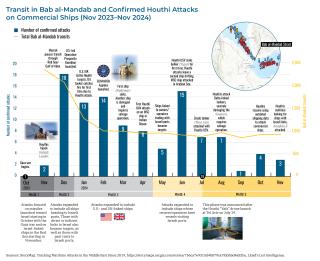

During the Gaza and Lebanon wars, the Houthis effectively turned the Bab al-Mandab chokepoint into an antiaccess/area-denial zone. A year after they seized the car carrier Galaxy Leader (IMO 9237307) and its multinational crew in the Red Sea, the maritime domain has turned into a key sphere of operations for the Iran-backed group. Using various types of weapons, the Houthis have so far conducted over one hundred attacks against commercial ships and warships since November 2023, announcing new shipping restrictions at every stage of their campaign (see The Washington Institute’s maritime incident tracker).

The attacks led to the formation of different regional defensive naval missions, including the U.S.-led Operation Prosperity Guardian and the European Union-led Operation Aspides. The presence of Western navies has been instrumental in certain areas, such as intercepting Houthi weapons, escorting some merchant vessels, and salvaging stricken ships. The Poseidon Archer military strikes, conducted in “self-defense” by the United States and Great Britain with nonoperational support from other countries, were also necessary to target Houthi weapons stocks and launching sites. So far, however, they have not deterred the group.

As 2025 approaches, the current high maritime risks could either increase or gradually decrease. This will largely depend on how the incoming U.S. administration addresses the Gaza war, which the Houthis have been using to justify their attacks, and on Iran. A ceasefire in Gaza should theoretically pave the way for a diplomatic solution to the Red Sea crisis. A serious solution, however, will require the involvement of U.S. regional partners that saw transit to their ports affected by the Houthi attacks. On the other hand, if the Trump administration pursues a tough policy toward Iran, commercial ships could face more hybrid risks. Either way, the next administration’s Middle East policy will directly influence the maritime domain in the region.

Evolution of the Houthi Campaign and Key Maritime Trends

The Houthis have so far divided their maritime campaign into five phases:

- Phase 1: Attacks focused on missiles launched toward Israel starting in October 2023 with the Gaza war and on Israel-linked ships in the Red Sea starting in November 2023.

- Phase 2: Attacks expanded in December 2023 to include all ships heading to Israeli ports. Those with direct or indirect links to Israel also became targets, as well as those with past visits to Israeli ports.

- Phase 3: Attacks expanded in January 2024 to include ships linked to the United States and Great Britain.

- Phase 4: Attacks expanded in May 2024 to include ships whose owners/operators have vessels visiting Israeli ports.

- Phase 5: This phase, announced following the launch of the Houthi’s “Yafa” drone at Tel Aviv on July 19, 2024, builds on the previous stages.

In each phase, the group was able to force more and more vessels to avoid the southern Red Sea. In phase 4, and since at least late April 2024, additional shipping companies that trade with Israeli ports have been avoiding voyages via the Bab al-Mandab. Meanwhile, on certain occasions, the attacks brought attention to other activities in the region, such as Russian oil trading (see this Maritime Spotlight post).

Houthi attacks and Russia-linked ships. The Houthi-led campaign has brought attention to tankers transporting Russian oil to the Asian market. These included the Panama-flagged crude oil tanker Cordelia Moon (IMO 9297888), which the Houthis wrongly labeled as “British” when they attacked it in October. In fact, when the attack occurred, the tanker was associated with India-based Margao Marine Solutions OPC, which is connected with ships involved in Russian oil trading. The Cordelia Moon was sailing in the region after offloading a cargo of Russian crude at India’s Jamnagar refinery. Research for this report also revealed that the tanker had previously sailed in the area without any issues. It is unclear if the Houthis decided to attack the ship in October because fewer vessels that fit their list of targets are now sailing in the region. In November, attacks against commercial vessels dropped to only three confirmed incidents, from fourteen in June (see The Washington Institute’s maritime incident tracker).

Russia-linked tankers are among the vessels that still transit the Red Sea. An analysis by Lloyd’s List Intelligence shows that in addition to Russia-linked vessels, ships associated with China, Greece, the United Arab Emirates, and Turkey are currently among the “most active users” of this route. However, this does not mean that these vessels are completely immune to attacks, as the Houthis often attack using outdated or inaccurate shipping data.

Varying reactions to the Red Sea crisis. Transit in the Bab al-Mandab Strait is still down by over 50 percent year-over-year. The Red Sea crisis has created challenges for regional ports and key navigational routes like the Suez Canal, where the number of transits plummeted from around 2,068 in November 2023 to about 877 in October 2024, according to data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence.

But the crisis brought financial benefits to some too, as certain companies profited partly due to high freight rates as they rerouted ships around southern Africa. Meanwhile, others saw financial opportunities in the Red Sea and launched new shipping services despite the high risks, such as SeaLead, a Singapore-headquartered company (see this Maritime Spotlight post).

Container shipping giants like Danish A.P. Moller-Maersk (Maersk) continue avoiding the Gulf of Aden and the southern Red Sea, taking the Cape of Good Hope route instead. The long haul has raised bunker fuel consumption and overall operating costs, which in turn has led to higher freight rates and profits.

In contrast, other leading shipping companies have maintained some transit via the southern Red Sea. The most prominent is French liner CMA CGM, which has continued to operate an Asia-Mediterranean service that transits through the region. In general, ships that transit through the Bab al-Mandab need to be escorted by warships, though they are not escorted every time.

Additionally, the Red Sea crisis forced some producers to relocate, benefitting certain countries. For instance, research for this report shows that as the distance increased for transporting cargoes between Europe and Asia, some producers in Europe decided to move to Jebel Ali in Dubai, shortening the trip by avoiding the voyage around southern Africa,

What Lies Ahead in 2025

Although U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) forces intensified airstrikes against Houthi weapons launchers and storage facilities inside Yemen in mid-October, the impact on Houthi military capabilities remains limited. Since January 2024, Western coalition forces have struck Houthi targets in Yemen at least seven times, most recently on November 9 and 10, using highly capable carrier-borne F-35C stealth aircraft for the first time. While most of those strikes targeted Houthi weapons in various stages of preparation before launch and the coastal radars supporting them, the strikes occasionally also targeted larger weapons warehouses, storage bunkers, and assembly lines. In January 2024, the Biden administration redesignated the Houthis a specially designated global terrorist group, but unsurprisingly, this did not change their maritime behavior.

Whether the next administration makes any marked changes in its approach toward Houthi behavior will largely depend on its stance on maritime security and freedom of navigation. Securing the southern Red Sea should also involve regional allies and partners to share the costs of this process. This will require strong regional alliances with clear operational mandates to more effectively interdict Houthi supply lines.

In addition, what lies ahead in 2025 for the security of shipping lanes will depend largely on the level of Iran-U.S. tension as well as the war in Gaza. During Trump’s first term, amid tough U.S. sanctions on the Iranian oil industry, Iran was blamed for several maritime attacks in the Persian Gulf region (see The Washington Institute’s maritime incident tracker). If the next Trump administration also takes a hardline stance against Iran, retaliation can be expected in the maritime domain similar to what happened between 2018 and 2020, but this time, the Houthis will likely be even more involved.

The policy of the Trump administration could lead to the removal of between five and six hundred thousand barrels per day (b/d) of Iranian oil from the market by mid-2025 and bring Iranian exports down to about 1 million b/d from nearly 1.6 million, according to data shared at a recent event organized by Kpler, a market intelligence firm. In such a scenario, Iran, and even the Houthis, could retaliate against ships, including in areas that are not considered their traditional zones of operation. For instance, the two could intensify collaborative drone attacks against commercial ships, such as those with links to the United States and Israel in the Arabian Sea. Maritime incidents can also be expected in the central Indian Ocean involving long-range weapons and mother ships as staging points for sea mining, aerial drones, cruise missiles, unmanned surface vehicles (USVs), or uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUVs).

If key U.S. partners in the Persian Gulf are seeking to contribute to lasting stability as they focus on economic development, and if the new administration wants to actively promote peace in the region, Washington should push for close cooperation with regional states like Saudi Arabia on maritime security and policies toward Iran. This will require diplomatic pressure, especially as Saudi-Iranian relations have apparently continued to improve since the China-brokered deal between the two in 2023. At the same time, if the Trump administration is planning to focus on maximum pressure on Iran, it should be prepared for the potential consequences and maintain, or even expand, its regional presence.

Noam Raydan and Farzin Nadimi are senior fellows at The Washington Institute and co-creators of its Maritime Spotlight series.