The facility is seemingly intended for launching surprise maritime interdiction missions in the Persian Gulf region, mainly aimed at U.S. Fifth Fleet assets—though it probably won’t be able to accommodate Iran’s potential future fleet of Russian jets.

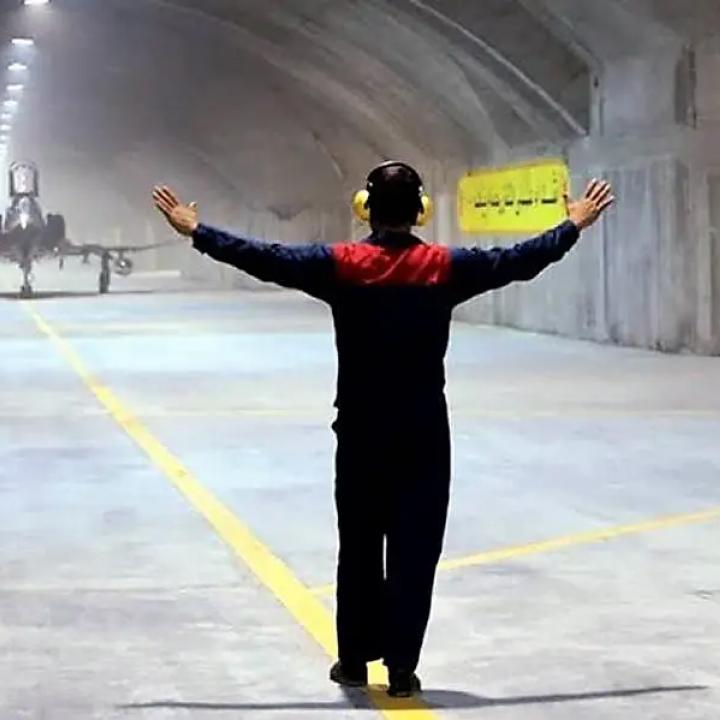

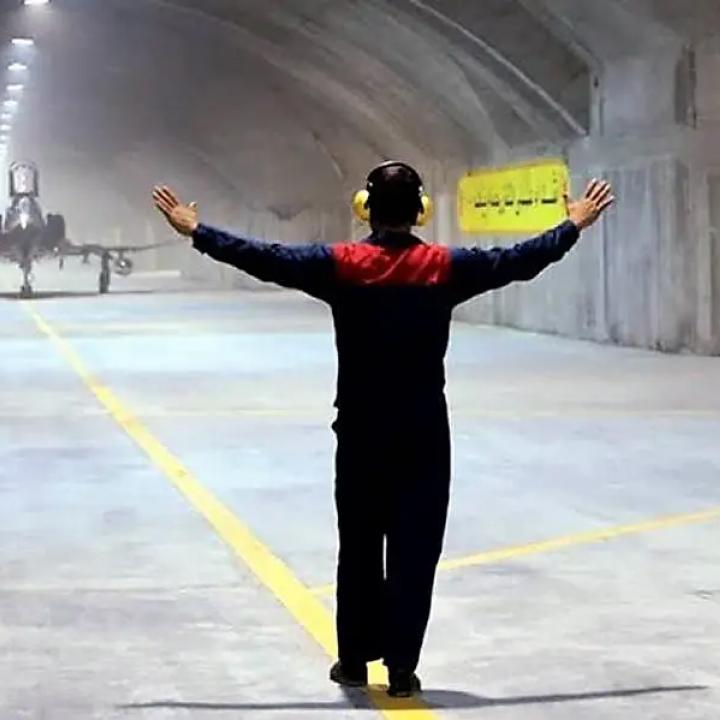

On February 7—the official anniversary of the day when air officers joined the 1979 Islamic Revolution—Iran unveiled the Oghab-44 Hybrid Tactical Air Base, located 120 km northwest of Bandar Abbas in a remote area of Hormozgan province. Despite being built well inland, the unfinished facility essentially overlooks strategic shipping routes in the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz. The Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force (IRIAF) calls the base “hybrid” because it is intended to accommodate both manned and unmanned aerial assets; the question is which assets, and what threat they might pose to U.S. and allied targets.

Iran’s “Eagle Nest”

The new base’s name references both the Farsi word for “eagle” and the forty-fourth anniversary of the revolution. Iran often announces aviation achievements on this anniversary, but Oghab’s unveiling was deemed special because—in the words of Gholam Reza Jalali, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) general who heads the Passive Defense Organization—it could be a “game changer” in a time of war and will force the “enemy” to reconsider its military calculations. The fanfare was also presumably aimed at countering the recent Juniper Oak military exercise, the largest set of drills ever conducted in tandem by the Israel Defense Forces and a U.S. joint regional command.

For his part, armed forces chief of staff Maj. Gen. Mohammad Bagheri stated that underground air bases like Oghab would expand Iran’s deterrent power beyond its known missile and proxy capabilities by putting airpower back on the table. Without a survivable basing system, Iran has had little hope that its air force could remain viable in a war with a major military power. Moreover, the IRIAF has been noticeably underfunded compared to the IRGC and even other branches of the regular armed forces (Artesh). According to Bagheri, the new hardened base and future sister facilities will shore up those weaknesses by accommodating new fighter jets and protecting them from enemy bombs and missiles in the event of a conflict. Yet can Oghab live up to that claim?

The apparently large underground complex is dug into an Asmari limestone rock formation, with four north-facing entrances connected to an uncovered 3 km surface runway whose construction began in May 2021 (though the complex as a whole appears to be significantly older; see below). Aircraft will be able to reach the runway via two partly covered taxiways stretching 1.4 and 1.8 km. The connecting taxiway tunnels would also seem to work as alert areas.

The choice of location was partly predicated on the notion that its unique topography would make the base less vulnerable to air and missile attacks, with mountain ridges providing protection on the north and south. Yet these obstacles will hardly be formidable enough to affect the highly accurate hypersonic gliding munitions that Iran’s adversaries will be fielding in the near future (assuming they cannot penetrate the base with existing conventional weapons). Similarly, the heavy blast doors intended to protect the facility’s entrances do not appear to be as highly rated against tactical nuclear blasts as similar facilities elsewhere in the world. And despite being housed in hardened bunkers, aircraft would still need to take off and land via the more exposed taxiways and runway, which remain vulnerable to high-kinetic heavy ordnance. The underground tunnel network may present problems as well—although it appears capable of accommodating several aircraft with their support equipment, fuel storage, and maintenance/arming spaces, it also seems to lack proper ventilation and firefighting pipes, so sustained operations there could prove highly dangerous.

In any case, construction appears to be incomplete at present. Work is still being carried out under the supervision of the Khatam al-Anbia Central Headquarters, whose main job is to oversee Artesh and IRGC operational preparedness. Similar underground air bases in Taiwan, the former Yugoslavia, and Sweden took about eight years to finish at a cost of at least $1 billion each. In Oghab’s case, Sentinel 2 satellite imagery shows significant excavations in the area for the past several years.

Implications for Iran’s Fighter Fleet

Along with Bagheri’s recent comments, the inauguration of Oghab-44 and other hardened air bases suggests that Iran might resume its push for more modern airpower. For example, recent reports indicate that it might take delivery of twenty-four Russian Su-35S multirole fighters in return for supplying suicide drones and other weapons to Moscow. The batch of fighters in question was originally produced for Egypt but remains undelivered, mainly due to U.S. political pressure and Cairo’s dissatisfaction with the aircraft.

Yet even if a deal with Iran is in the works, delivery does not appear imminent—there is little indication of the normal preparations that would precede implementation of such a major military transaction (e.g., air and ground crew training in either country). Perhaps Moscow intended the news to serve as a warning to Western governments—namely, if they send F-16s or other modern fighter jets to Ukraine, Russia will give Su-35s to Tehran.

Basing Su-35s at Oghab-44 seems improbable as well. The facility’s tunnels were apparently designed to allow movement of F-4 Phantoms, F-14 Tomcats, and Su-24 Fencers, whose wingspans range from 10.3 to 11.8 meters; the larger Su-35, with a wingspan of 15.3 meters, is unlikely to fit.

Yet despite rushing to exploit the Ukraine war by cementing a strategic partnership with Russia and potentially acquiring new fighter jets and other advanced weapons, the IRIAF’s mainstay is still the fleet of F-4 Phantoms that were purchased from the United States before the revolution. An F-4E can carry a full combat load of 2,700 kg to a range of 840 km, or two antiship or cruise missiles to as far as 1,000 km before firing them. In the latter case, Iran’s Nasr antiship missile can achieve a range of 70 km; the Phantom can also carry other antiship missiles with ranges as long as 300 km, or larger cruise missiles such as the Asef and Heidar, which can travel significantly farther at low altitudes before reaching their targets (their air-launched ranges are in excess of 1,000 km and 200 km, respectively).

These capabilities may help explain why Iran would want to spend so much effort and money on an underground air base at a time when it has a very limited number of operational combat aircraft, and when the modern Russian jets it hopes to purchase are seemingly too large to operate there. Armed with long-range antiship missiles and standoff smart munitions, aircraft taking off from Oghab-44 could provide some measure of surprise first-strike capability, as well as a second-strike capability to retaliate against U.S. capital warships (especially aircraft carriers), amphibious groups, auxiliary ships, and regional bases. Because the complex has been under construction for several years, it was likely intended with one major purpose in mind: launching surprise attacks against U.S. warships throughout the Gulf region, especially carrier strike groups. The USS Ronald Reagan Carrier Strike Group completed the last such deployment in the region in September 2021; previously, carrier groups were often stationed in the Fifth Fleet’s theater of operations within striking range of Iran when tensions with the regime rose.

Conclusion

Some aspects of Oghab-44 might lead observers to believe it was intended for an air defense role (e.g., its connecting tunnels could double as alert areas, which would be unnecessary for preplanned strike missions). Yet this role has already been prominently assigned to Iran’s expanding ground-based air defense network with very few fighter jets involved. More likely, then, Oghab is designed to serve as a secure forward operating base that supports maritime interdiction operations as part of Iran’s antiaccess/area-denial strategy, mainly using its small F-4 and Su-24 strike aircraft detachments from Bandar Abbas and Shiraz air bases at first, as well as unmanned platforms in the future. If Iran does eventually receive Su-35 jets from Russia, the base probably cannot accommodate them (perhaps it was designed before Tehran envisioned purchasing larger jets such as the Su-35).

Yet even without more modern aircraft or a larger fleet, Iran’s expensive new underground air bases could give it some degree of aerial first-strike capability against U.S. naval assets in the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, and Arabian Sea, perhaps including efforts to close the Strait of Hormuz to shipping and naval traffic. Building such bases could also spur other countries in the region to add hardened underground facilities to their existing air bases or construct new bases with this capability.

Farzin Nadimi is an associate fellow with The Washington Institute, specializing in security and defense in Iran and the Gulf region.