- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3709

Israel Expands Settlements as Smotrich Increases His Authority

Amid widening West Bank violence, the far-right minister is pursuing a policy leading to de facto annexation, and it is unclear whether Netanyahu will cap these ambitions.

On February 22-23, an Israeli government panel advanced plans to construct over seven thousand new housing units in various settlements, the largest such decision ever issued at a single planning meeting. The panel also scheduled a March meeting to discuss objections to the highly contentious E-1 project east of municipal Jerusalem, which would block north-south Palestinian contiguity in the West Bank. Israel has previously pulled back from building E-1 amid U.S. pressure, but the rise of far-right parties in Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s government makes it unclear whether this pattern will continue.

Meanwhile, a power struggle continues to unfold between Defense Minister Yoav Gallant and Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who also holds ministerial rank in the Defense Ministry. Most recently, Netanyahu agreed to transfer significant control over civil affairs in the West Bank to Smotrich, an ideological leader of the settler movement who has made the “inevitability” of annexation a leading policy objective. Although Smotrich’s ultimate goal is to permanently eliminate the possibility of Palestinian statehood in the West Bank, he realizes that Netanyahu cannot simply annex the territory by fiat due to international diplomatic constraints. Thus, his current focus is on de facto annexation through incremental steps outside the security barrier—a strategy that may proceed unnoticed at times given Israel’s domestic political convulsion over proposed judicial changes and ongoing flare-ups in violence with the Palestinians.

The power-sharing agreement between Smotrich and Gallant creates an unprecedented situation wherein civilian officials will hold key positions in the military bodies responsible for West Bank civil affairs, while officials in the Israel Defense Forces will ostensibly focus on security matters. Yet the distinction between civil and security matters in that territory is blurry at best, and the defense establishment has warned that the new arrangement will threaten unity of command. (For more on these issues, see the separate section on civil control below.)

Taken together, the settlement decisions and ministry rearrangements will significantly expand Israel’s presence beyond the security barrier, further diminishing the prospects for a two-state solution. The situation also complicates U.S. efforts to de-escalate severe Israeli-Palestinian tensions ahead of Ramadan, which is expected to begin March 22 and overlaps with Passover this year, potentially increasing the risk of violence.

On February 26, Washington, Egypt, and Jordan sought to address these tensions head-on by holding the Aqaba Summit, a rare public meeting attended by officials from both Israel and the Palestinian Authority. In the resulting joint communique, the PA and Israel agreed to “end unilateral measures for a period of 3-6 months,” with Israel specifically committing “to stop discussion of any new settlement units for 4 months and to stop authorization of any outposts for 6 months.” Afterward, however, Smotrich and other far-right ministers rejected the communique altogether. Notably, U.S. officials admit that the understandings reached at Aqaba did not include rescinding the settlement and outpost approvals that Israel announced earlier in February.

De Facto Annexation?

According to media reports, Netanyahu has privately told foreign officials that he has no plans to annex the West Bank at this time, in part because doing so would undermine budding ties with the Gulf states. Indeed, the UAE made “no annexation” a precondition for signing the 2020 Abraham Accords, and any breakthrough with Saudi Arabia would presumably require the same provision at minimum.

As noted above, however, Smotrich and others are betting that further construction outside the security barrier will eventually reach a tipping point and become de facto annexation. In addition to complicating the future delineation (even theoretical) of a separate Palestinian state, continuing to advance settlement construction in such areas would almost certainly exacerbate local tensions and clashes over time.

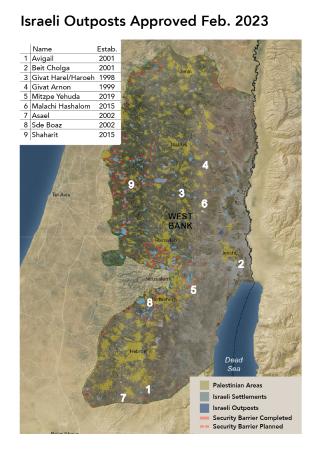

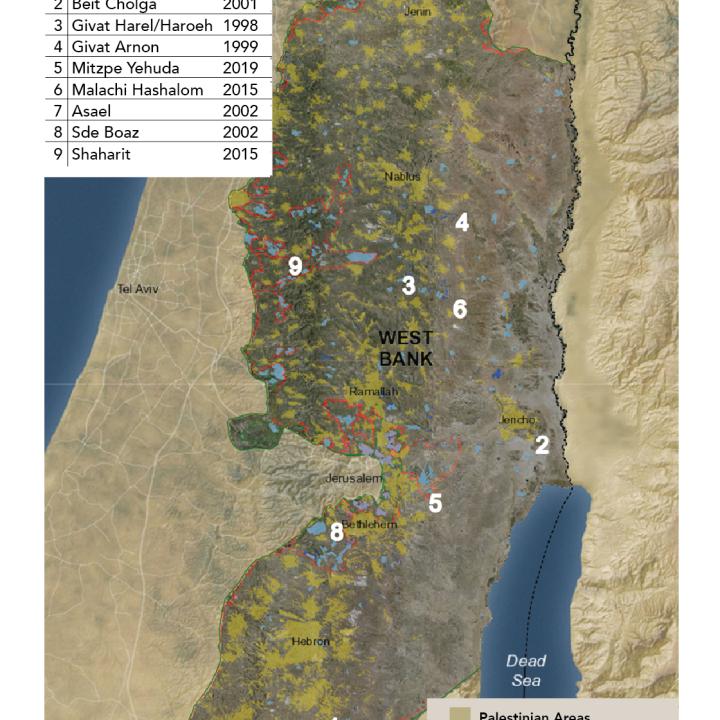

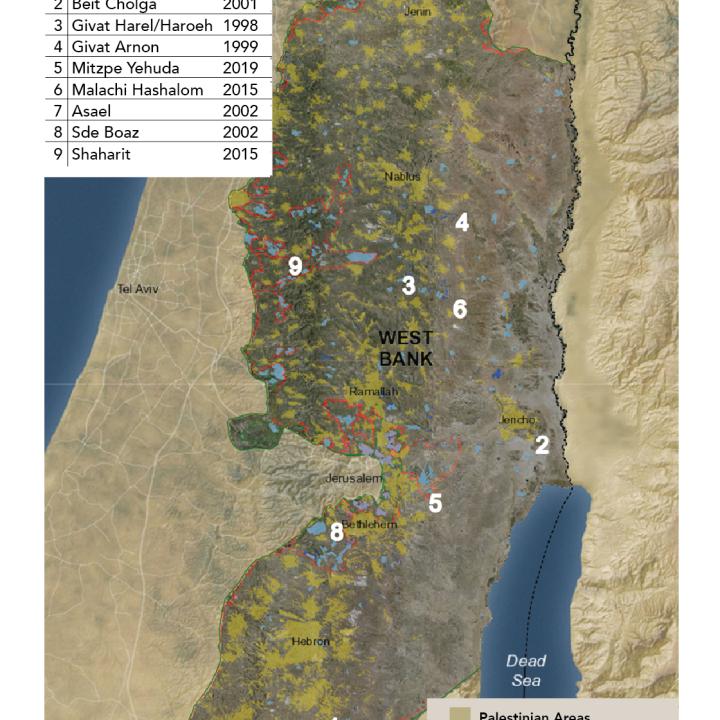

The security barrier, while not a border, is key to understanding the possible contours of an increasingly threatened two-state solution. Most Israeli settlers live in government-approved settlements located inside this barrier (comprising around about 8% of the West Bank), while a large majority of Palestinians live outside it (92% of the West Bank). Put another way, approximately 84% of Israelis residing on the other side of the pre-1967 Green Line live in 52 approved settlements located inside the barrier, while the remaining 16% (approximately 115,000 people) live in approximately 78 approved settlements outside the barrier. (For the sake of this discussion, the 84% figure includes Israeli residents of East Jerusalem. The 115,000 figure does not include any of the estimated 15,000-20,000 settlers living in outposts, see below. For more on these demographic and territorial issues, see The Washington Institute’s interactive mapping tool “Settlements and Solutions.”)

The February 22-23 approvals will begin to change these proportions if implemented in full. Previously, groups of Israeli settlers established 106 outposts without the government’s authorization, in many cases partly or fully on private Palestinian land. Most of these outposts (92) were built outside the barrier, and their populations range from dozens of people to a few hundred. Combining government-approved communities and illegal outposts, a total of roughly 170 settlements have been established outside the security barrier. On February 12, the government announced plans to legalize 9 outposts, 7 of them outside the barrier. If that plan holds, Israel will have 85 approved settlements outside the barrier and 84 unrecognized outposts (two outposts will be combined into one legalized settlement).

Construction Steps

Approving new construction in West Bank settlements often takes years. Overseen by the Higher Planning Committee of the Civil Administration, the process entails several steps before ground can be broken on a project, including (1) deposit of plans, (2) a sixty-day period to hear objections, and (3) validation of final government approval. Building in larger settlements often requires public issue of construction tenders as well.

Regarding the 7,098 settlement units advanced in February, 72.3% are still in the deposit stage and 27.7% are in the final validation stage. The cabinet actually committed to advance 10,000 new units, but authorities in the affected settlements likely did not have sufficient plans ready on short notice, so the remainder will probably be deposited at a meeting scheduled for May. The previous two governments held these Higher Planning Committee meetings less frequently, but Netanyahu’s cabinet has pledged to resume a quarterly schedule and will likely be more open to approving projects quickly. Hence, even if further outpost legalization and settlement construction approvals are temporarily frozen due to understandings such as the Aqaba communique, 2023 could still become the most intensive period of settlement construction approval since before the 1990s Oslo process. In the current batch alone, 58.3% of the new units are slated to be built outside the barrier.

Outpost Legalization

Many outposts have been purposefully built near strategic West Bank arteries in order to prevent the creation of a contiguous Palestinian state and force the Israeli government to assert control over more land. The cabinet portrayed last month’s decision to legalize 9 outposts as a response to the killing of 9 Israelis in recent terrorist attacks in Neve Yaakov and Jerusalem (a tenth victim died after the government had already notified Washington of its decision). In truth, however, 7 of these outposts were already in the early phases of the legalization process.

The latest move is particularly significant because no other outposts had been legalized as separate settlements since 2012 (though several had been retroactively legitimized as “neighborhoods” of existing settlements). The scope of this legalization may counter Gallant’s attempts to maintain existing policy through periodic demolitions of unauthorized construction. Regardless of any political agreements, settler groups such as Nachala will no doubt rush to construct more outposts in the hope they will be retroactively legalized.

Yet completing the legalization process can take several years, and court challenges may still be in the offing. Three of the outposts slated for legalization—Avigail, Givat Harel/Haroeh, and Givat Arnon—were partially built on private Palestinian lands whose owners can petition the Israeli Supreme Court to stop the process. Such legal impediments have long vexed the settler movement and are a major reason why Smotrich’s Religious Zionist Party strongly supports legislation to thwart the high court’s independence.

Smotrich Wins Civil Control

To secure more authority over civil affairs in the West Bank, Smotrich has waged an intense, weeks-long dispute with Gallant and threatened to veto the defense budget if his demands were not met. Netanyahu ultimately sided with Smotrich by dividing the powers of the Civil Administration and the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT).

Specifically, Smotrich was permitted to appoint a civilian deputy head of the Civil Administration, giving him expansive powers over land surveying/registration, settlement construction, outpost demolition, infrastructure projects (e.g., water, electricity, transportation), and other matters. Gallant and the IDF will retain control over security issues, while Netanyahu will resolve any disputes between the two on high-profile issues such as outpost demolitions and major new construction. Yet even seemingly minor decisions under Smotrich’s purview (e.g., hooking outposts up to water and electricity lines) will create facts on the ground. He is regarded as a highly energetic administrator and will surely use his new powers to advance measures that the United States opposes.

Policy Implications

Netanyahu appears to be pursuing two contradictory tracks simultaneously. On one hand, he has sought to placate officials in Washington, Arab capitals, and even Israel’s own security services by pledging to pause new outpost legalizations for now. All of these players want to tamp down Israeli-Palestinian tensions before the expected Ramadan/Passover turbulence. Yet actions on the ground can quickly foil political decisions—during the Aqaba talks, for instance, two Israelis were killed in a terrorist attack in the Palestinian village of Hawara, spurring hundreds of settlers to launch a riot that killed one Palestinian and destroyed buildings and cars. IDF Central Command chief Maj. Gen. Yehuda Fuchs publicly referred to the events as a “pogrom” and took responsibility, saying the IDF was not prepared for such a large settler assault. In contrast, Smotrich declared that Hawara should be “erased,” though he added that he did not want there to be loss of life. The Biden administration called Smotrich’s remarks “disgusting” and urged the Israeli government to prosecute those responsible for the riot.

On the other hand, Netanyahu is strengthening Smotrich’s authority to drive settlement expansion over time, in keeping with his longstanding tactic of appeasing far-right elements so they stay in his coalition. The prime minister seems willing to take this step even when it means unprecedented division of authority in the West Bank, where the IDF has long been the undisputed authority. The February construction approvals and the deal to give Smotrich partial civil control may be just the beginning, and the full impact of these moves may not be felt for some time. In the end, Netanyahu will not be able to placate everyone, and there is growing concern over whether he fully controls his government given his reliance on the Religious Zionist Party to stay in power. In the meantime, Smotrich is betting that his newfound political clout will help him make major progress toward his goals.

David Makovsky is the Ziegler Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute and director of its Koret Project on Arab-Israel Relations. David Patkin and Gabriel Epstein are research assistants in the Koret Project.