- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4022

Leveraging the Gaps in Russia and China’s Complex Relations with Iran

Far from signaling a strong trilateral alliance, their history of often transactional cooperation reveals strategic gaps that Washington can leverage to help curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

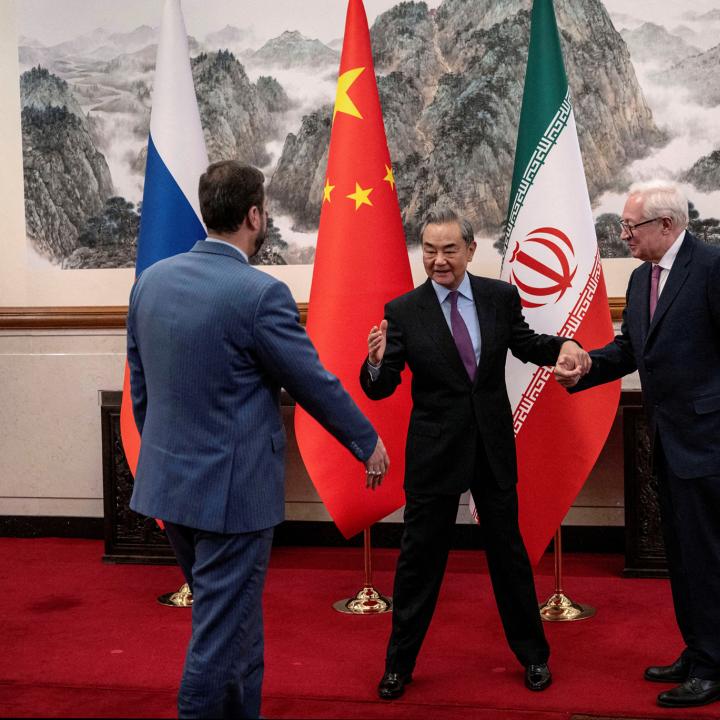

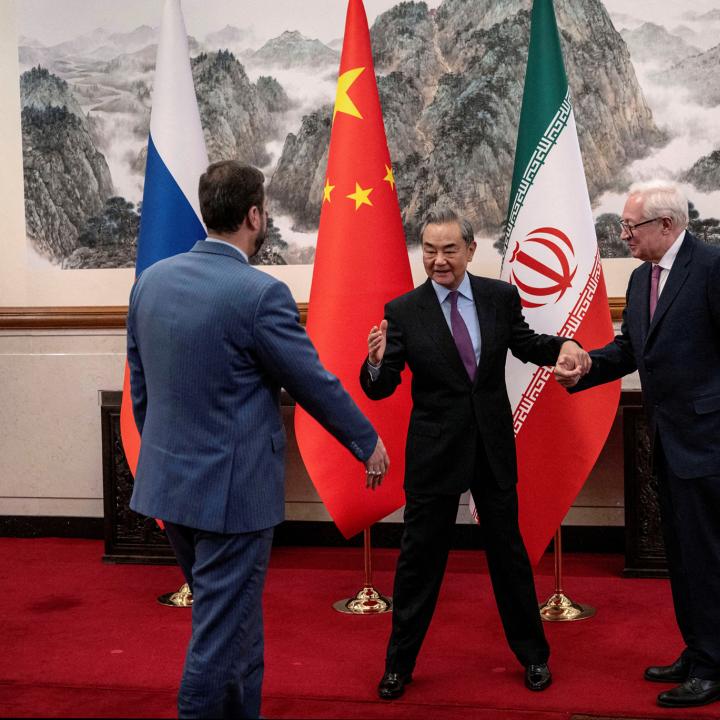

For all the hoopla that preceded it, the trilateral China-Iran-Russia meeting on Tehran’s nuclear program did not appear to generate anything of great significance. The joint statement issued after the March 15 Beijing gathering largely echoed previous such documents, from condemning “unlawful unilateral sanctions” against Iran to reiterating a mutual desire for a diplomatic solution. That said, the mere act of holding the meeting may have been the objective, to signal to the world that the three countries stand together.

This show of unity could have immediate practical effects given the partial expiration of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in 2025—including the “snapback” provision that permits the UN to reimpose full sanctions on Iran if a JCPOA participant triggers the mechanism. At the same time, the three governments still have diverging historical and strategic interests on a range of issues—differences that will not dissipate just because they hold a joint meeting and share friction with the United States. If Washington hopes to exploit these fault lines, however, it must properly understand them.

Is a Repeat of 2002-2006 in Store?

In December 2006, China and Russia joined the rest of the UN Security Council in adopting Resolution 1737, which imposed UN sanctions on Iran for the first time. Their decision reportedly shocked Tehran because it came after they had spent several years actively obstructing international efforts aimed at holding Iran accountable for its nuclear activity. The diplomatic repercussions from 1737 also encouraged the United States and its partners to go back to the council a few months later to adopt Resolution 1747.

Here again, however, China and Russia’s actions led many observers to draw exaggerated conclusions about their strategic alignment. In reality, neither government believed it had to take permanent sides on the nuclear issue—rather, Iran had irritated them by refusing to negotiate seriously after they offered a P5+1 package in June 2006 and issued a warning resolution in July. Once 1737 was adopted, they shifted back to helping Iran by watering down the sanctions. This was a pattern they repeated in subsequent years by working as a bloc to soften sanctions, encourage Western concessions, and steer Tehran away from radical reactions—the same strategy they used with North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. Yet despite working together, they came at the issue from different strategic angles.

China’s Approach

Beijing’s core objective in the Middle East is to maintain good relations with all local powers and ensure a steady energy supply from a region that has supplied around half of its oil imports over the past decade. Some observers speculate that China wants to displace the United States as the major foreign power in the Middle East, while Beijing has stated that its intentions are more neutral—as seen, for instance, when it helped mediate the last stages of Iranian-Saudi detente in 2023.

Regardless of its long-term aspirations, China’s resulting approach to the region is the same: pursuing policies that avoid conflict and preserve its reputation as a broadly neutral party. This stance essentially prevents it from taking Iran’s side in any permanent sense, despite helping Tehran evade sanctions. (Beijing’s positions on Israel are more complex and linked to its posture toward the United States, but are beyond the scope of this PolicyWatch.)

Russia’s Approach

In contrast, Moscow does not have an intrinsic interest in safeguarding the free flow of Middle East energy exports or, by extension, avoiding conflict in the region (though crucially, it may be averse to certain conflicts under certain circumstances, as discussed below). If nothing else, the Middle East represents a source of competition for Russia’s own fossil fuel exports, even after the creation of OPEC+. Hence, it is less concerned about broad neutrality, instead focusing on its closest partners in the region, Iran and Syria (at least prior to Bashar al-Assad’s ouster).

Russia’s approach to Iran has long been transactional, especially since the advent of the nuclear issue. More often than not, Moscow has viewed the relationship as a lever to extract concessions from the United States in bilateral matters. For example, in 2010, Russia openly signaled its willingness to support Security Council Resolution 1929 on Iran’s nuclear program if Washington agreed to unfreeze the U.S.-Russian nuclear cooperation agreement, put on ice by the invasion of Georgia. President Obama accepted this tradeoff as part of the broader bilateral reset then underway. Moscow also paced its cooperation with Tehran at times in order to manage relations with Washington and offset U.S. pressure (e.g., by delaying progress on the Bushehr nuclear power plant and the delivery of S-300 air defense systems).

In later years, Russia continued this approach under the Biden administration by offering to convey U.S. messages to Iran, probably in the hope of extracting benefits from both sides. The 2022 invasion of Ukraine ended this role, though the Trump administration has apparently encouraged Vladimir Putin to take it up once again.

Of course, developments over the past few years have raised real questions about whether Russian ties with Iran are now a distinct relationship rather than just a lever against the United States. Some analysts have noted that the relationship changed due to both countries’ mutual support for the Assad regime in Syria. Assad’s fall suggests that Moscow may be in the market for a new strategic partner in the Middle East. Russia’s imperial history with Iran has challenged such ambitions in the past—for example, when the Iranian public found out that authorities permitted Russia to use a northern air base for bombing runs during Syria’s civil war, howls of outrage ensued, and the campaign was shut down. Yet that diplomatic snafu occurred years before the Ukraine war, during which Iran has openly provided substantial military support to Moscow in the form of missiles and drones.

If this support has shifted Russia’s historically paternalistic attitude toward Iran, it might indicate a broad reorientation of Moscow’s objectives in any future mediation, including on the nuclear issue. Most notably, Russia may now have a considerable stake in avoiding any large-scale U.S./Israeli military action that risks endangering its prospective new ally in Tehran, or that gives the U.S. military another chance to demonstrate success at a time when Russia’s military has comparatively failed in Ukraine.

Policy Implications

As the United States and its partners once again embark on resolving the Iran nuclear issue, they would be wise to probe and exploit the strategic gaps discussed above. If the past is prologue, Tehran’s general strategy will entail working with Russia and China to offer tepid compromises in order to avoid escalation, delay snapback, and prevent military strikes. Beijing and Moscow have already sided with Iran at the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Board of Governors, seeking to avoid resolutions that would either require the regime to cooperate fully with IAEA monitoring requests or, failing that, formally find it in noncompliance with its nuclear obligations. This mirrors their approach from 2002 to 2005—before they ultimately relented in September 2005 and eventually agreed to UN sanctions in 2006.

Today, one can imagine Russia and China seeking an alternative diplomatic path at the next meeting of the IAEA Board in June, proposing a new process for voluntary inspections in order to derail any European attempt to refer Iran back to the Security Council or trigger snapback independently. If snapback becomes inevitable, the three partners would likely work together on managing Iranian retaliation in a way that casts blame on the United States and its partners for any escalation (e.g., by spinning Iran’s stated intention of withdrawing from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty as giving the regime legal authority to pursue whatever nuclear activities it likes).

As the engagement process unfolds, one thing should be clear to the Trump administration: Russia and China will not support maximalist U.S. demands such as dismantling Iran’s nuclear fuel cycle. Although neither partner likely wishes to see the Islamic Republic gain nuclear weapons, they have historically blocked any deep or permanent impingement of what they consider to be Iran’s nuclear rights—a view reiterated in their March 15 joint statement. Yet the United States should be able to create a ceiling for Iranian nuclear escalation by warning that it is prepared to act militarily if, for instance, Tehran develops a nuclear weapon and/or takes unacceptable actions upon withdrawing from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (e.g., permanently ending IAEA monitoring, openly enriching uranium to weapons-grade, etc.). Washington could then press Russia and China to persuade Iran that it must go no further than its present “nuclear threshold” status.

Moreover, the United States still retains the option of working with Beijing to cut Iranian oil revenues. This could include an agreement to sharply restrict Tehran’s access to money from oil sales to China even if oil continues to flow. Ironing out the details of these restrictions would necessitate careful U.S. handling of complex questions (e.g., if Tehran is permitted to purchase Chinese “humanitarian” goods with the restricted revenues). Yet the right balance of limits, U.S. monitoring, and economic realpolitik could wind up giving Washington a major lever during eventual nuclear negotiations. Crucially, any oil revenue agreement need not be public to be effective.

In return, Beijing would likely demand accommodations on U.S.-China issues. Some of these demands may be acceptable to Washington (e.g., reducing trade pressure); others would not be (e.g., abandoning the Uyghurs or Taiwan).

Similarly, Moscow’s recent offer to mediate with Iran doubtless comes with an expectation that the United States will reciprocate by easing sanctions related to Ukraine. Making such concessions would be exceedingly risky at a time when the dimensions of the new Iran-Russia relationship are not yet fully understood. For instance, Moscow could wind up using some of the relief it receives from Ukraine sanctions to help rearm Iran or otherwise support its partner. The Trump administration should therefore regard any such offers with extreme skepticism, placing strong guardrails and conditions on any sanctions relief over Ukraine—and, indeed, on any Russian offers to help with Iran.

Richard Nephew is the Bernstein Adjunct Fellow at The Washington Institute and former deputy special envoy for Iran at the State Department.