UN limits on Iranian weapons transactions will expire in a few short months, and even snapback sanctions may be insufficient to prevent proliferation of dangerous arms to and from the regime.

On October 18, all restrictions imposed on Iran as part of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) will expire, and Tehran will be technically free to sell or import almost any weapons it desires. Its thirst for reentering the realm of international military collaboration and arms exchanges seems keen, as evidenced by its recent joint naval drills with Russia and China and other developments. Meanwhile, years of sanctions have led to advances in Tehran’s own weapons manufacturing industry, creating further proliferation hazards and threats to regional stability. The question is whether allowing the 2015 restrictions to expire will exacerbate these dangers, and what the United States and its allies can do about it.

IRANIAN ARMS ACTIVITY BEFORE AND DURING SANCTIONS

Between 1989 and 2007, Iran conducted numerous transactions with other nations to bolster its military arsenal. It purchased a steady stream of combat aircraft, submarines, main battle tanks, armored personnel carriers, and antiaircraft missiles from Moscow and Beijing, and engaged in collaborative design and production of antiship and antiaircraft missiles with them. It imported parts and hired weapons experts from these and other countries. And it matured key weapons programs such as the Shahab-3 medium-range ballistic missile, development of which involved internationally sourced components and assistance from North Korea, among others.

Yet many of these exchanges came to an end in 2007, when UN sanctions gained momentum in response to the exposure of Iran’s covert nuclear program. As a result, Tehran began to invest more in its domestic military industry and know-how. This shift, combined with reorganization of its armed forces and military strategy, helped the regime achieve some noteworthy advances on its own, such as producing and fielding a wide range of antiship, ballistic, and cruise missiles, developing a respectable drone industry, and reinforcing most of its air defense network using domestically produced radars and surface-to-air gun and missile systems. Iran’s recent missile attack against U.S. forces at al-Asad Air Base in Iraq involved two such domestically developed weapons, the Qiam-1/2 and Fateh-313.

Even so, Iran still suffers from technological bottlenecks and must still import certain raw materials (e.g., specialized alloys) and key components (e.g., high-performance propulsion systems). It also hopes to secure Chinese and Russian know-how and collaboration on designing and building its own next-generation heavy warships (7,000-plus tons) and submarines. Such oceangoing vessels are required to meet the regime’s goal of becoming a blue-water naval power.

Toward that end, Tehran and Beijing signed a defense cooperation memorandum in 2016. More recently, Hossein Khanzadi, commander of the Islamic Republic of Iran Navy, traveled to China last April, and a delegation led by Armed Forces General Staff chairman Mohammad Bagheri visited in September to discuss future high-level scientific and industrial cooperation. Bagheri also offered Beijing a twenty-five-year defense cooperation agreement whose secret contents were specifically endorsed by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. China apparently has not responded to this offer yet, but it sent a defense and naval delegation to Tehran in November to explore operational and technological cooperation.

Meanwhile, Bagheri traveled to Moscow in February 2019 to follow up on similar defense cooperation agreements. Unconfirmed reports also indicate that Iran has offered to buy a significant number of Russian fighter jets in return for discounted crude oil.

Such cooperation with either country could take more meaningful shape when UN restrictions expire in October. This will also depend on whether U.S. sanctions continue in their current form.

WHERE THINGS STAND TODAY

Since the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 2231 in 2015, various restrictions have been placed on Iran’s weapons-related activities. Paragraph 5, Annex B of that resolution bars all member states and their nationals from supplying, selling, or transferring certain types of weapons to Iran either directly or indirectly, unless approved in advance by the council (view a table detailing all UN limits on Iranian weapons). These restricted systems are limited to battle tanks, armored combat vehicles, large-caliber artillery systems, combat aircraft, attack helicopters, warships, missile systems, and related materiel, including spare parts. The paragraph does not explicitly state whether “related materiel” includes raw material, modification kits, or dual-use items, but there is legal ground for assuming that at least the first two are covered. Also subject to the council’s preapproval are the provision of technical training, advice, and related financial resources/services to Iran.

According to the UN Register of Conventional Arms, the missiles covered by this provision include “guided or unguided rockets, ballistic or cruise missiles capable of delivering a warhead or weapon of destruction to a range of at least 25 kilometers, and means designed or modified specifically for launching such missiles or rockets.” The latter subcategory includes drones with missile characteristics, such as the ones used in the September attack on Saudi Aramco oil facilities. It also includes rocket-assisted mortars; Iran is a major producer of such weapons, various calibers of which are in wide use throughout the Syrian and Iraqi conflict zones. Yet the provision excludes most surface-to-air missiles, with the exception of man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS).

Unfortunately, none of the resolutions aimed at Iran have managed to significantly curtail its missile program, due in part to their diluted language on the matter. Resolution 2231 merely “called upon” the regime not to undertake any launches or other activity related to ballistic missiles “designed to be capable of delivering nuclear weapons”—a vague and unverifiable definition by design. This provision will remain in force until October 2023, but Iran has been making steady progress on such missiles for years despite the restriction, and can be expected to continue doing so in the future unless it agrees to a comprehensive security deal with the West.

Paragraph 6(b), Annex B of Resolution 2231 applies similar restrictions on “the supply, sale, or transfer of arms or related materiel from Iran by their nationals or using their flag vessels or aircraft, whether or not originating in the territory of Iran.” Member states are required to take the necessary measures to prevent such activities, though the passage does not specify which arms are restricted.

At times, Iran has sought to get around these restrictions by openly transferring permitted systems to its proxies abroad, then covertly transferring restricted components to be added to those items later. For example, it has reportedly provided Iraqi Shia militias with Safir and Aras unarmed tactical vehicles, only to later smuggle prohibited parts that allow them to fit the vehicles with rocket launchers and 106 mm recoilless guns.

ROLE OF THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION MECHANISM

Under the JCPOA’s dispute resolution mechanism, if any parties to the nuclear deal believe that Iran is not meeting its commitments, they can refer the matter to the Joint Commission for resolution. On January 14, the European parties (Britain, France, and Germany) took that step in response to Iran’s recent moves away from the nuclear deal. If this matter or any future disputes remain unsolved after exhausting the resolution process with good-faith efforts, the Security Council must vote on a resolution to continue the effective suspension of previous resolutions and their associated restrictions. The council must adopt this new resolution within thirty days, which simply will not happen because the United States would surely exercise its veto.

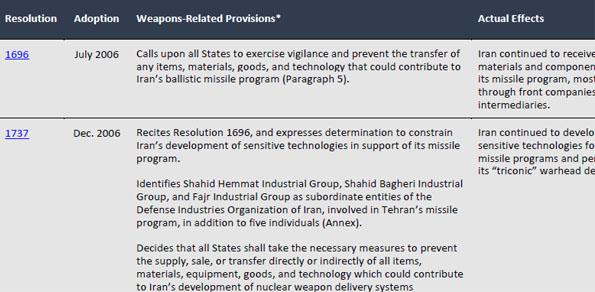

If the new resolution fails, then previous resolutions would “snap back” into force, including UNSCR 1696, 1737, 1747, 1803, 1835, 1929, and 2224. As the table below shows, these older resolutions include various nonnuclear provisions that could theoretically offer a strong international mandate to prevent weapons cooperation with Iran. Unlike the JCPOA limits, the restrictions in these older resolutions never expire; they last until the Security Council votes to repeal them, an action over which the United States has veto power.

Yet it is difficult to envisage any snapback mechanism deterring Iran from delivering arms to its regional proxies, since it has continued to do so over the years under various resolutions, using methods that are tough to prevent (e.g., placing ammunition boxes on passenger seats of chartered civilian airliners). Moreover, snapback sanctions cannot be retroactively applied to contracts that Iran has previously been permitted to sign with other parties while under the JCPOA.

CONCLUSION

At present, there is little prospect that the Security Council will sponsor any initiative to extend the current weapons restrictions past October. However, the United States could use the current enrichment dispute, Europe’s apparent readiness to get tougher on Iran, and Tehran’s latest threat to quit the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty as cause for compelling a snapback situation.

In any case, Washington should increase its individual efforts to discourage China and other countries from cooperating with Iran on sensitive military technology and know-how. It should also prepare for even greater proliferation of attributable and nonattributable Iranian weapons throughout the region’s flashpoints, in part by scrutinizing the regime’s transfer and logistical routes even more closely.

Farzin Nadimi is an associate fellow with The Washington Institute, specializing in the security and defense affairs of Iran and the Gulf region.